The Poisoning Angel (3 page)

Read The Poisoning Angel Online

Authors: Jean Teulé

Madeleine Le Braz, ruled by Breton superstition, carried out the test of the ten candle ends, which she had cut to equal length. Five were placed on one side of the stricken woman, for death, five elsewhere, for life. The latter went out much sooner. ‘The patient’s had it,’ the farm labourer’s chubby wife predicted matter-of-factly.

‘Is there someone coming?’ asked Jean.

Anatole looked out of the cottage’s one small window to check. ‘No, why?’

‘I thought I heard a cart jolting along.’

Madeleine was already strewing mint, rosemary and other aromatic leaves on the soon-to-be corpse. ‘We also have to empty the water from the vases lest, at any moment, the dead woman’s soul should drown there.’

Madame Le Braz executed this task while Jean, helpless and at a loss, not knowing how he could make himself useful, automatically reached for a broom handle.

‘No, no

scubican anaoun

(sweeping of the dead)!’ advised Madeleine. ‘You never sweep the house of someone who’s about to die because their soul is already walking around and the strokes from the broom might injure it.’

The farm cottage filled with sighs, though everyone was admiring of Thunderflower’s zeal and devotion as, head bowed, she took such care of her sick mother, whose tongue was now green, flecks of foam hanging from her lips. Had they been able to see the small blonde girl’s expression from underneath, however, they would have discovered something infernal about it. She was standing beside someone who was about to die … It was like the birth of a vocation. As she put her little fingers to one of her genetrix’s burning cheeks, it was like the child Mozart touching the keys of a harpsichord for the first time. She murmured something the adults took for a sob,

‘Guin an ei …’

(‘The wheat is germinating …’) and her mother died, lowering only her right eyelid, which put Madame Le Braz in an instant panic: ‘When a dead woman’s left eye doesn’t close it means someone else you know is in for it before long!’

‘That’s true, Hélène. You’re right. The blade of the Ankou’s scythe is fixed to the handle the opposite way round. But how do you know that at your age? In any case, the scythe belonging to Death’s worker is different from those of other harvesters because its cutting edge faces outwards. The Ankou doesn’t bring it back towards him when he cuts humans down. He thrusts the blade forward, and he sharpens it on a human bone.’

Her father demonstrated the gesture on the moorland, silver grey with lichens.

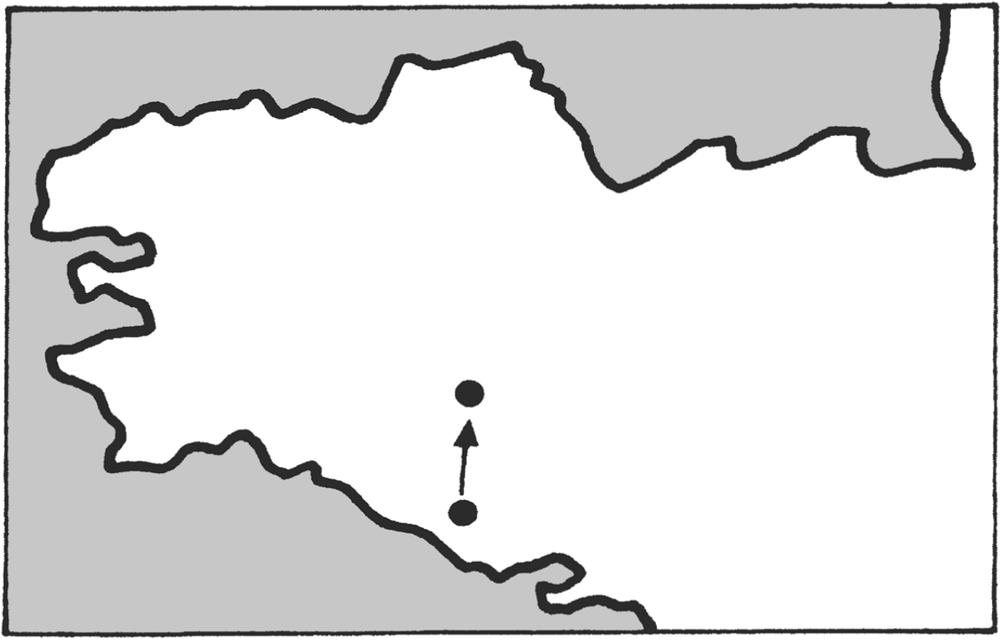

‘Like that, well out in front. D’you see? But why are you concerned with that? Just as your big sister, Anna, is in service with the parish priest at Guern, you’re about to go to join your

godmother in the presbytery at Bubry, to work in abbé Riallan’s household. You’ll have to call him “Monsieur le recteur”. What do you think you’ll be scything over there?’

‘Papa, are there people in Bubry?’

‘Yes, it’s quite a large village.’

‘And is there belladonna there?’

‘Of course. Why wouldn’t there be?’

Hélène was biting greedily into a slice of bread when the dainty carriage belonging to a haughty gentleman arrived. He got out, exclaiming, ‘Well now, Jégado the royalist, I expected to see you wearing blue. Aren’t you in mourning?’

‘In Lower Brittany, husbands never mark their widowhood, Monsieur Michelet. Only the animals on the farm observe mourning rituals. I put a black cloth over my hive and made my cow fast on the eve of my wife’s funeral. You may as well learn that now, because you never know, you old revolutionary – who are soon to be married,’ added Jean as he noticed the embroidery on the ribbons fluttering from the back of Michelet’s hat, a sign that he was engaged.

The well-turned-out visitor – still young, square-shouldered, with a bearded jawline, and sporting a white leather belt and laced-up shoes – appraised Jean’s two stony hectares, which stretched as far as the line of plum trees leading to the washing place.

‘So you’re selling your whole farm?’

‘Even with Anne it was difficult. I’ll never manage on my own. I’ll leave you the cottage as it is, with contents. I’ll just take my sword from above the fireplace.’

‘What will become of you, nobleman?’

‘Day labourer … beggar … I’ll do what my neighbours do. You’re well aware of the poverty and how many abandoned farms there are in the hamlet of Kerhordevin, since you’re the one buying them all up.’

‘How much do you want for yours?’ asked the wealthy landowner.

‘One hundred.’

‘You must be joking! It’s not the Jégado château at Kerhollain I’m getting. I’ll give you fifty but, since I’m going through Bubry anyway, I’ll drop your daughter at the priest’s house as promised. That’s a very pretty little fairy you’ve got there. How old is she?’

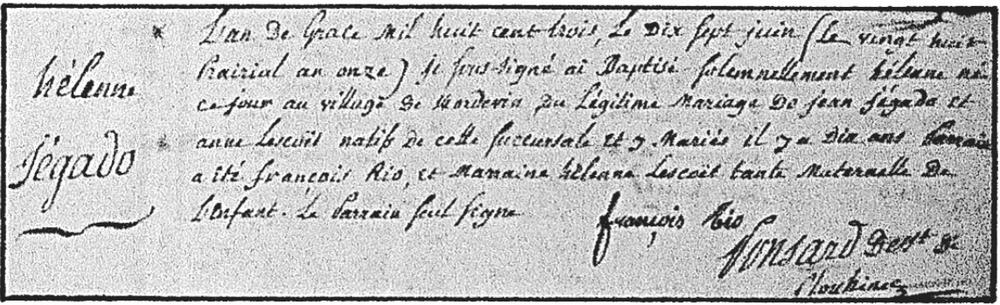

‘She was baptised on 28 Prairial in year XI.’

‘Year XI. Can’t you say 1803? Are you still using the revolutionary calendar, Jean? Alas, that fine secular invention of the Great Revolution is over. An erstwhile Chouan like you should be rejoicing that we’ve gone back to the Christian calendar, the Gregorian one …’

‘Oh? I didn’t know that. The only way those of us who can’t read the papers have of hearing about important events is from songs at fairs, you see.’

‘Go on, my little noblewoman, up you go into the carriage with your leather bag. It has a fleur-de-lis branded on it. Is it your father’s? What have you got in it?’

‘A cake I made.’

‘Right. So, Jégado, you’ll let me have your hovel?’

Pulling out a hair – the symbol of property – Jean threw it into the wind. This was the equivalent of signing a contract, declaring that you would not go back on the agreement, since it would be impossible for the seller to recover the hair, which the breeze had carried away.

The hair spiralled away in the wind, and the carriage, drawn by a mare, rolled off along a rutted road shaded by centuries-old oak trees. Putting her bag, which was divided into two sections, beside her, Thunderflower turned to watch her downcast father making his way back to the cottage. Soon the child lost sight of the Druid stones of her village as well.

Late afternoon. The bell was ringing for the angelus. The light, two-wheeled carriage came at walking speed past numerous flour mills and squat windmills and stopped in front of the presbytery in Bubry. The wealthy landowner was lying motionless on his side, with one arm hanging down. His discarded whip lay on the flour-scattered cobbles. Behind the presbytery gates a woman in servant’s clothing and with bagnolet fluttering on her forehead called out, ‘Monsieur le recteur! Monsieur le recteur!’

A priest came running to join the servant, who was wiping her hands on her apron and asking Thunderflower in Breton, ‘What’s the matter with him? He’s got foam at his mouth and cake crumbs in his beard!’

‘He’s dead, Tante Hélène. It came over him just as we arrived in this street.’

‘Oh, my poor little godchild, what a journey you must have had.’

The priest raised Michelet’s head and gave his diagnosis in French. ‘He must have had a heart attack.’

For the second time in her life, Hélène Jégado was hearing this strange language, of which she understood not one word.

‘Petra?’

(‘What?’)

She was looking now at the façade of the priest’s residence, with carved coats of arms broken during the Revolution, while he was astonished by the sight of her blond mop of hair.

‘Mademoiselle Liscouet, your late sister’s daughter goes bareheaded?’

‘Girls don’t wear a headdress except at

fest-noz

until they’re thirteen, abbé Riallan,’ his servant reminded him.

‘What do you enjoy doing?’ the clergyman asked the girl in

brezhoneg

.

‘Cooking, Monsieur le recteur.’

‘Fine, then you’ll help your godmother peel the vegetables, wash up, put the stores away in the outbuilding, and learn French. Give me your bag. Goodness, the man who brought you here lost not only his life but one of his shoelaces as well.’

In the presbytery kitchen, Thunderflower was having her hair done by her godmother. Standing opposite a piece of broken mirror fixed to the door, the Jégado girl glanced at her reflection from time to time. Behind her back she could see her mother’s sister smoothing her long blond hair out towards the top of her head and rolling it into a chignon, and then she felt hairpins sliding in against her scalp.

The niece gave a hasty glance to the right. She asked for a pause before her aunt should go on to the next phase of the hairdressing, just long enough for her to go and dip a ladle into the saucepan and blow on the surface of the broth to drive the gathering froth to the edges.

‘You must always remove it as it forms. You were the one who taught me that, Godmother, as well as the correct way to brown butter. Will you teach me lots of other things?’

‘A good cook never gives away all her little secrets,’ smiled her maternal aunt, who was dressed in a Lorient apron with a large bib that covered her shoulders. ‘Come on, back here.’

Once back in position in front of the door with the piece of broken mirror, Thunderflower passed a significant milestone: a Breton headdress was positioned on top of her chignon. It was just a simple square of white tulle, as befitted a domestic, but it was edged with lace. Her godmother explained how it was arranged, folding it here, turning it up there, in the local manner.

‘Each district has its own kinds of embroidery and folds. There we are, now everyone can see you’re a grown-up girl. Just look at you with your mane neatly tamed at last. Wouldn’t anyone think you were an angel fit to receive Holy Communion without the need for confession first?’

Thunderflower burst out laughing, caught in a ray of sunlight that lit up a sideboard, and she saw her reflection swing round as the abbé Riallan opened the door and came into the kitchen, asking, ‘Who would you give Holy Communion to, Mademoiselle Liscouet?’

‘Why, my goddaughter, of course. We can only congratulate ourselves on her.’

The priest of Bubry noticed the headdress. ‘Are you thirteen already then?’

‘This very day, 16 June!’ exclaimed her godmother.

‘That calls for a celebration,’ said the gentle, elderly priest. ‘I was about to leave for Pontivy to meet the abbé Lorho, who will

be replacing me soon. Would you like to come with me, Hélène? While I’m at the church you could buy some goodies, as it’s your birthday, and also whatever we need to sort out the rat problem in the outbuilding before my successor gets here.’

‘Of course, with pleasure,

aotrou beleg

.’

‘Monsieur le curé,’ the clergyman corrected the girl.

‘Oh, yes, sorry … Of course, Monsieur le curé.’

With that she undid the ties on her apron while the man of the Church heaped praise on her.

‘That’s all right. The French language will come. Still a few Bretonisms sometimes, but you’re making excellent progress.’

Once outside the presbytery gates, while a stable boy was harnessing a clapped-out pony to the cart into which the priest clambered with some difficulty, Thunderflower had a good look at the village of Bubry, a higgledy-piggledy collection of houses with water troughs, a firewood seller and, above all, mills. Near the market where meat was sold, a butcher reminded Riallan he should send someone for what was due to him: ‘… because when an ox or pig is slaughtered the head is kept for Monsieur le curé.’ Hélène was just lifting her buckled shoe on to the running board when she stood back down, most astonished to see, across from her on the other side of the road, the two Norman wigmakers who had overturned their cart in a rut one day at Plouhinec.

In front of the torn yellow cover, and beneath the lettering ‘À la bouclette normande’, the short wigmaker was setting out chairs and getting scissors ready while the taller one – almost bald, with a black band over his left eye – was clapping his hands, calling to people, ‘Five sous per head of hair! Who wants to earn five sous in exchange for their hair?’

Beside the wall where the Normans were making their preparations, there stood three posts with rusty iron chains hanging from them. Workmen covered in flour were coming out of a mill for their lunchtime break. They had long hair touching their shoulders and covering their eyes. They kept pushing their long locks behind their ears, creating a cloud of dust, while the wigmaker tried to sound conciliatory.

‘Even though we’d prefer it neat and washed, there’s no problem, good sirs. We’ll still buy your hair as it is. Take a seat.’

But it was the three posts the workers were making for, each mortifying himself as he went: ‘How I regret my wicked deed! I should never have done that! Oh, I’ve done such a bad thing, I’m so angry with myself!’ They leant their foreheads against the posts and wound locks of their hair through the rings, all the while reproaching themselves: ‘I said nasty things to my mother! I robbed my brother! I betrayed my neighbour!’ Then they yanked their heads violently backwards, tearing out their hair, which came away together with the scalp. On the ground traces of blood and skin could be seen, to the stupefaction of the two Norman wigmakers, who were hopping up and down now.

‘What are you doing? You’re mad! What savagery! That’s unbelievable! Where on earth are we? If you think we’re going to pay five sous for raggy bits of scalp …’

The Normans were shouting so loudly that their surprised horse instinctively kicked out its back hoofs, catching the weedy wigmaker – who had just gone between the shafts to fetch a basin hanging on the front of the cart – full in the jaw and breaking one of his shoulders as well. The tall, one-eyed man snatched up his colleague and bundled him under the yellow canvas, then, abandoning the chairs, leapt on to the vehicle seat and whipped

the horse, which galloped off northwards. Reins in hand, he turned and yelled at the self-torturing Bas-Bretons, ‘Sickos! Nutters!’

The inside of the pharmacy at Pontivy resembled a sacristy in hell – smocked employees speaking in hushed voices, jars labelled in Latin, mysterious little packets. The man in charge of the establishment, who wore a monocle, asked, ‘Who’s next? You, pretty maid? What would you like?’

‘Reusenic’h.’

‘What?

‘Reusenic’h!’

‘Oh, arsenic.’

‘Yes, for killing rats. The priest at the presbytery in Bubry where I work in the kitchen told me to buy some while he went to his meeting.’

The pharmacist turned round, then proffered a minuscule bottle.

‘That’s light,’ Thunderflower said, weighing it in her hand.

‘Ten grammes, but it’s to be used with the greatest of care,’ admonished the man of science as he took the servant’s money. ‘This substance is very dangerous.’

‘But not as dangerous as belladonna.’

‘Oh, much more so, my dear,’ he said, handing her the change. ‘The doses must be infinitesimal. Be very careful, won’t you? Don’t go using it for pastries just because you’re from Bubry. It may look like flour, but it’s not the same at all.’

‘Kenavo.’

*

Just as Thunderflower was pulling open an oven door, the abbé Riallan pushed open the kitchen one, and came in, scratching his tonsure.

‘Hélène, I’m telling you this as truthfully as I would say the angelus: I do not understand. Since you put that white powder in the outhouse, the rats there have been getting fatter and fatter and their numbers are increasing.’

‘Oh?’ answered the adolescent, carefully placing a burning hot tray on the clay tiles.

‘I saw one the size of a cat against the grain chest. They’re swallowing the product from the chemist’s, which is supposed to exterminate them, yet it’s as if they were stuffing themselves without suffering any harm. Is there any of it left? I’d like to try again.’

‘No, I’ve emptied the bottle,’ said Thunderflower, sliding a spatula under one of the little cakes on the tray and putting it onto a dish.

‘When your aunt comes back from the market, please ask her to come and see me at the church. Oh dear, dear, whatever will the abbé Lorho think of me?’ worried the rector, pushing open the glass door to the courtyard, just before Hélène’s godmother came in by the other door, carrying baskets and sniffing.

‘Mmm, there’s a lovely smell of caramelised crust in here.’

Her goddaughter, carefully washing a bowl and a spoon, told her, ‘While you were out, I tried to invent a cake. Monsieur le recteur would like to speak to you.’

‘Let’s taste your speciality first.’

The niece advised her aunt to blow on it because it was hot. ‘Since I was able to buy some, thanks to the priest giving me money for my birthday, I’ve put crystallised angelica in it.’

‘That’s very kind.’

Putting the small round caramelised cake between her lips, Hélène Liscouet bit into it and began to chew. Her face flushed, there was instant dryness of the mouth and mucus membranes, and she was gripped by a raging thirst.

‘Something to drink!’

Weakness of the muscles and dizziness followed, and then she could no longer stand, and her legs gave way beneath her.