The Poisoning Angel (4 page)

Read The Poisoning Angel Online

Authors: Jean Teulé

âSo the priest at Bubry didn't call the doctor immediately, then?' a servant, hands on her hips, asked Thunderflower, who was leaning on her elbows at the table in a different kitchen.

âYes, he did, Tante Marie-Jeanne. But when he reached the bed where Godmother was thrashing about like a mad thing, he just put some dust into a box. He drew a cross in it and said, “In the name of the Father,” adding, “The patient will be cured if she gives a few sous to Saint Widebote.” I've kept the last towel she wiped her lips on as a memento.'

In pride of place on the table stood a loaf of rye bread beside a sickle-shaped knife. Thunderflower ran her finger lovingly along the blade as her second maternal aunt lamented, âYou poor girl.

Both my sisters: your mother, then your godmother.'

âWhat's more,' complained Thunderflower, âI'd just baked a little cake I'd invented for her. I couldn't even find out whether she liked it. I'd intended one for the abbé Riallan too, but with all the fuss I forgot to serve it to him. I've brought it in my bag â would you like to try it?'

âHave you put ground almonds in it?'

âThey're in there too.'

Â

âOh, yes, you're right, Mother. At eighteen, Hélène is quite magnificent! She'll turn a few heads, that one, and in my opinion it won't be long before she finds a young man.'

The priest of Séglien, a real gentleman who was surely very popular with his parishioners, was seated in the depths of an armchair across from his mother, who was sipping her lime tisane. On the low table between them stood little cups of plums in syrup, newly brought by Thunderflower. As his very pretty servant left the drawing room for the kitchen, the clergyman turned to watch.

âDid I tell you, Mother, that her aunt Marie-Jeanne, who was in my employ for many years, dropped dead the very day her niece arrived to see her, following a death in their family?'

âI didn't know that.'

âIs it really that long since you've ventured outside the walls of Saint-Malo to visit your son, lost among the savages of Basse-Bretagne, you heartless mother?' the priest joked.

âSince I was widowed I don't travel much, and it's a long journey here on such rough roads that you fear death with every

turn of the wheel. What did Marie-Jeanne die of? Your father always said that fatal dysentery was rife in the area where you serve.'

âThat's right. Lots of people also suffer attacks of virulent skin diseases. In any case, since Hélène had already worked in a kitchen and was talented, I entrusted her with her aunt's job and I'm very satisfied with her. A kind heart, dedicated to her work, clean, and she gets on like a house on fire with my maid.'

The priest's mother said approvingly, âYour father always said that, these days, finding a cook of the right calibre â¦'

Thunderflower returned with a plate of biscuits, which she put down, then, turning round, exclaimed in tones of mock-disgust, âOh, look, there on the carpet behind you, mouse droppings. Monsieur l'abbé, we'll have to buy something to kill rats. I was just thinking that, since your mother's here, I could take this opportunity to go to the pharmacy at Pontivy.'

The abbé Conan leant down to pick up what his cook had pointed out. âThose aren't rodent droppings, they're coffee beans. Just now, when you were using a hammer to grind beans wrapped in a cloth, some must have escaped and rolled on to the carpet. I'd have been very surprised in any case, since I've had the place cleared of rats.'

Hélène gave a forced smile at being thwarted.

âHave a rest now, Hélène,' the good priest suggested. âYou could even stay here with us and draw â you like that â instead of mouldering alone in your room.'

Madame Conan considered her son's attentions to be a little too progressive. With a Breton

sablé

crumbling in her teeth, she murmured, âYour father always used to remind us “To each

his own place ⦔ Having said that, it

is

sad to lose an aunt so suddenly.'

Thunderflower â strong and wholesome as bread and water, and statuesque, by God; to see her was to love her â was now seated elegantly at a card table, drawing swirls on a sheet of paper. âPerhaps Tante Marie was

goestled

,' she surmised.

âHélène means “dedicated”,' the rector of Séglien translated for his mother. âIn this region, when someone dies of an unexplained illness, people declare, “He or she's been dedicated to Notre-Dame-de-la-Haine.”'

âNotre what?' choked the widow, her mouth full of another biscuit.

âHave a little more tea to help it down. You see, Mother, before they were forced to convert to Catholicism, the Bretons here had altars dedicated to the death of others, and they've been determined to keep this cult going, as at Trédarzec, for example. Over there, Saint-Yves chapel was rebaptised Our-Lady-of-Hatred. People pray to Santez Anna, ostensibly the grandmother of Christ, but in actual fact Deva Ana, the grandmother of some Celtic gods â I think that's it. People go by night to the oratory to pray for someone's death.'

Madame Conan was stupefied. âAnd the Roman Catholic Church puts up with these outlandish practices within those walls?'

Thunderflower, all this while, was drawing drowning angels.

âOf course not,' her son replied. âThe rector of Trédarzec is determined to have the chapel torn down and the statue of Santez Anna turned into firewood.'

âYour father was so right when he used to say, “The language

that the Bas-Bretons have preserved, and their scorn for that of the French, is not conducive to the spread of new ideas in this region.”'

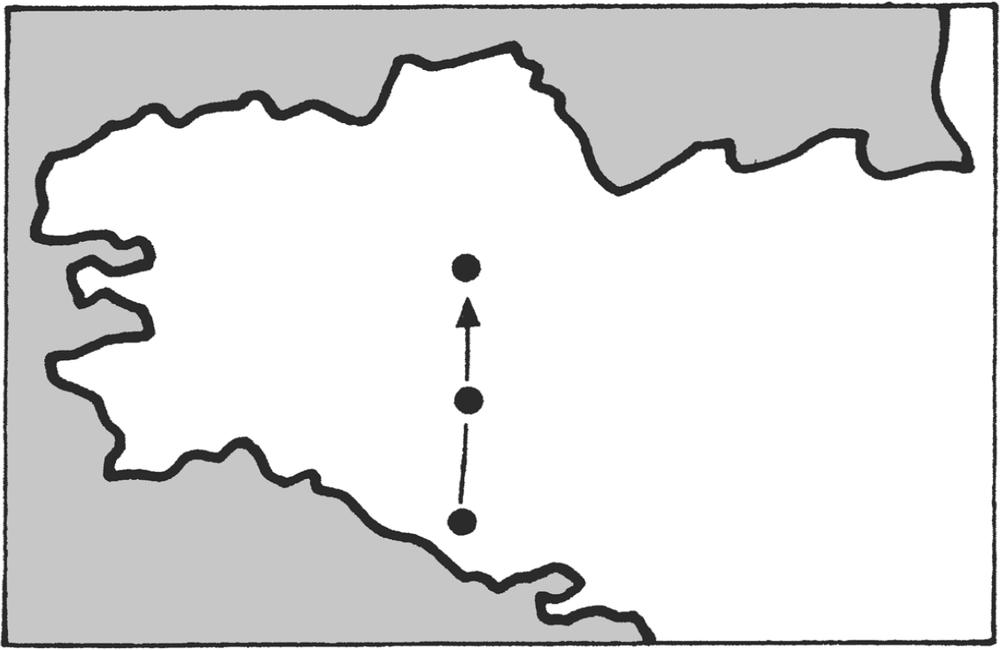

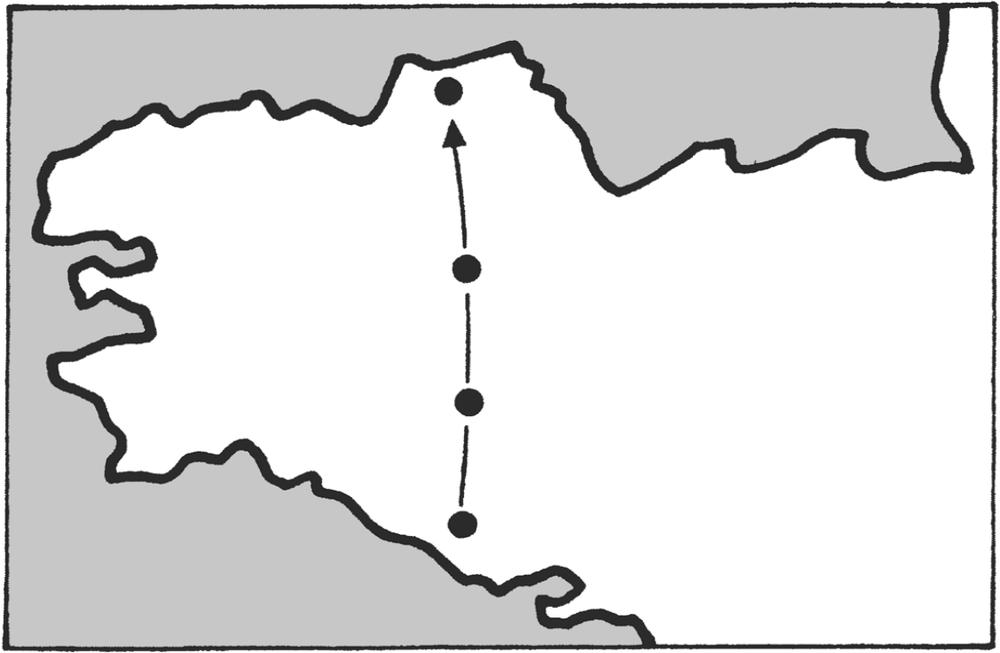

Scoring out the smudged wings of an angel lost amid the swirls, Thunderflower asked, âWhere's Trédarzec?'

âNot very far from here, across from Tréguier,' answered the priest.

âIn Morbihan?'

âNo, in Côtes-du-Nord, near the reefs in the Channel where the wreckers wait.'

âThe wreckers?'

The sun was folding away its fan and a few birds hovered high in the skies. The evening lengthened Thunderflower's shadow as she stood by the edge of a coastal river in Tréguier, watching the village of Trédarzec on the opposite bank. Her father's double-bag on her left shoulder, one part hanging in front, the other down her back, she spotted the oratory of Notre-Dame-de-la-Haine at the top of the hill. Several winding paths led to it across the gorse and heather. Soon, near a stone bridge spanning seaweed left stranded by the low tide, Hélène Jégado was overtaken by other human shadows. Ashamed, they slipped, heads bent, along the paths leading to the mysterious chapel. As darkness fell, more people approached the building. Bigoudènes, with their slanted

eyes and prominent cheekbones like Mongolian women, came forward like black birds, followed by workers and shopkeepers from Tréguier, who were whispering to one another, âLook, over there, that woman who appears to have gone into a decline, Rondel has dedicated her. It's only a matter of time now.'

They walked on, their bare feet burning on nettle leaves. Thunderflower followed them to where an instinct was guiding her. At the top of the hill, bare of greenery, she bent her head to slip under a doorway, and stood up inside the chapel whose beams were festooned with spider webs.

On the altar cloth stood the statue of Our-Lady-of-Hatred. It was actually a classic Virgin Mary, with wavy hair falling along her arms and hands folded, but her face had been given lots of wrinkles and her body was painted black with a white skeleton over it. At the time she was moulded, this plaster Mary had doubtless been very far from imagining that she would one day be travestied to this extent and venerated to the accompaniment of prayers as un-Catholic as the ones being addressed to her here.

âNotre-Dame-de-la-Haine, grant that my brother may soon be lying in his coffin.'

âI ask you for the death of my faithless debtors.'

All round Thunderflower, souls full of rancour were very softly invoking the so-called grandmother of Christ, asking her to grant them the death of an enemy or a jealous husband within a year.

âI want him to croak within this strict time limit.'

Some were in a hurry to inherit: âMy parents have lived long enough.'

Three Hail Marys piously repeated and the people were

ready to believe in the power of prayers offered in this church dedicated to the cult of death. The girl from Plouhinec was just thinking to herself that some fine dramas were underway around her when on her right she heard a man's gravelly voice: âOur-Lady-of-Hatred, send me a shipwreck.'

Thunderflower swivelled her head towards a fellow of about twenty-five, his complexion suggesting he was used to the rocking of the wind and the waves, who finished his prayer and left.

She followed him outside and asked: âWhat's your name?'

âYann Viltansoù. What's yours?'

It was his turn to look at her. Thunderflower's absolute perfection had something about it that froze him in his tracks. The extreme charm she exuded captured Viltansoù's heart instantly. âHave we seen each other in our dreams?' he asked.

âHow heavily you're breathing,' she said.

âThat's because it's hot,' he replied, in the cold night.

Â

âGulls, gulls, bring our husbands and our lovers home to us â¦'

The following afternoon, along a beach made of white sand and broken shells that looked like crushed bones, Yann Viltansoù was passing the time by singing the song of the sailors' companions under his breath: âGulls, gulls â¦'

Thunderflower, her dainty black buckled shoes in one hand, was walking barefoot alongside the former stable boy, who had had enough âof bedding down in the horses' manger to look after the animals'.

Now dressed in seaman's clothing from several countries â

baggy breeches like an English explorer, a red belt like a Spanish fisherman, a Dutch trader's tarred hat â he bent down to show the girl from Plouhinec how to gather razor clams, known here as âknife handles'.

âWhen the tide is out, you sprinkle salt on the sand. The creature thinks the tide's coming in. It wriggles up to the surface, and you grab it. I've also found you two river pearls.'

âThank you.'

Thunderflower, gazing out to sea lost in thought, felt an overwhelming emptiness inside her. The sight of this sterile infinity brought her to tears. Over there, the islands looked like sleeping whales and nearer to the shoreline, richly coloured rocky islets were like jewels set in the silvered foam of the waves. When the waves were high, shafts of light criss-crossed them in shimmering ripples, and cormorants glided into the bed of the wind. Their pulley-like cry was an answer to Yann's secret concern: âWill we catch any game from the sea tonight?'

Some men came towards Viltansoù, who raised his hand to his hat in greeting. One had a bare torso reminiscent of one of those wooden logs the sea throws up on the beach. A tall, bald individual, an incongruous mixture of eunuch and slaughterman, was conversing with an old man with lots of white curls about the way to save a drowning man.

âMight as well save their breath,' moaned Yann, examining the sea through his spyglass.

The waves took on a violet colour where there was seaweed underneath the surface. There was now a mixture of reflections and shifting light. In the distance, the boats went by, their sails furtively bleeding in the light of the setting sun. Some women

arrived on donkeys. On the customs men's path, bordered by thistles and brambles, a cow was grazing the granite. A wise woman foretold the future from the dance of the waters. Men knelt at the sight of the star of Venus. They were dressed in

berlinge

, a fabric of wool and hemp, out of which they made their yellowish brown waistcoats and breeches. Viltansoù observed the movement of ships in the distance, and noted sudden changes in the atmosphere. The noise of thunder shook the air. It grew suddenly dark and the wind whipped up the sea. Lightning flashed a zigzag course, and a bolt struck the coast.

By now, sky and sea were indistinguishable. Yann smiled, seeing the vessels suddenly headed for disaster. âCome to me!' he told them. âIt's a game.'

Leaving the sand to climb back up to the coastal path that skirted the edge of the cliff, Viltansoù, with Thunderflower in his wake, hung a heavy copper and glass signal lamp between the horns of the waiting cow. Lighting it, he explained to the girl from Plouhinec, âI'm burning coal because when the weather's bad, full of rain and fog, it gives a brighter light than oil burners, which get dull and are less visible on the horizon.'

Faced with the puzzled look of this splendid woman from Morbihan, who seemed not quite to understand what was going on, Yann from Côtes-du-Nord said by way of justification: âA ducal prerogative has given us the

droit de bris

, permission to help ourselves from wrecks washed up on the shore. But since natural shipwrecks beside the coast are fairly rare, we have to help destiny along a bit. Long live organised fate, and shoo!' he cried to the cow, which began to move, notwithstanding the weight of the gleaming lantern bowing its neck.

While the bovine hoofs trampled the stones, Thunderflower recalled, âRound the dunes where I'm from, when we want to find the body of someone who's drowned, we put a lighted candle on top of a loaf and set it adrift on the water. The corpse is found beneath the place where the loaf stops.'

Viltansoù was mocking. âIf we did that here the shore would be one big bakery.'

The wind blew the flame and harried the glass in the lantern. The sea grew increasingly angry. Yann was watching it from the top of a rock.

âThere! Over there! A boat's coming! Get the cow going! Oh, I did the right thing yesterday, going to pray to Our-Lady-of-Hatred!'

The bovine lighthouse made its way along the coast. The non-stop swaying of its head sent shimmering waves of light back and forth at regular intervals across the water. On board the vessel, the crew were deceived by the light, which they believed they could follow. It was the weather for a tragedy; shipwrecks seemed to be written in the stars. The former stable boy called to the ship, âThis way! Come! The way is clear and it ends in your death.'

Beneath her soaking wet headdress trimmed with lace, Thunderflower was licking her lips. The ocean was huge and fearsome, forming peaks and troughs, sometimes deep as the grave. The waters were raging so uncontrollably that it was as if the poles had lost their magnets. Viltansoù who, spyglass to his eye, could make out the vain efforts of the sailors on the bridge, gave precise information regarding the time and place of the collision.

âTen minutes from now, on the Maiden's Teeth rocks.'

And indeed, the ship was drifting towards the reef, with no hope of avoiding disaster.

âEveryone must perish,' said Yann.

âYes, oh, yes,' sighed the girl from Plouhinec.

Beneath the cliffs, the locals ran to hide behind the rocks across from the reefs indicated by Yann. Armed with hooked poles and ropes, they crouched down to wait, their eyes fixed on the dark waters and the sea's gifts with rapacious greed. Suddenly there was an enormous crack right in front of them, and splinters of boards flew about. On the Maiden's Teeth, a series of rocks where seaweed rotted, the ship had impaled itself as on a knife blade, which had sliced it like a fruit. And indeed, hundreds of thousands of oranges came tumbling from the gaping bow. Rushing towards the broken vessel came crowds of women and children with bags and baskets. Like a horn of plenty, the wreck was spreading a flotsam of luminous exotic fruit. Thunderflower came down quickly and filled her turned-up apron several times, making a pile all to herself on the sand. A wealthy trader from Saint-Brieuc, who owned the ship, had fallen overboard and was drowning, shouting for help in Breton:

âVa Doué, va sicouret!'

(âMy God, help me!')

âOf course we will. That's what we've come for,' guffawed the old man with the full white locks, beside the slaughterman with the face of a eunuch, who thought it perfectly fair to go and disembowel the trader and grab his belt, doubtless stuffed with gold coins.

Driven on by the demon of pillage, the coastal peasants hurled themselves furiously on the remains of the ship. They clubbed down the wretched survivors who were stretching out their arms

to them for help, stripped them, and mocked the drowned ship's boys who had been at table in the hold below.

âWhatever can have made those children so ill?'

âThey'd just eaten their bacon soup.'

âMaybe there was something wrong with the meat.'

Many of the sailors were thrown into the sea, sinking to the depths of a pitiless grave that instantly forgot their names. At the bottom of this natural abyss, the rocks were turning red. The play of the mists and foam made them appear to be moving. The women also climbed aboard port and starboard. They exuded a mad sexuality, clambering up phallic ropes wearing no undergarments, their skirts hoicked up on their bare thighs. Even bolder and more fearless than the men, they reached the height of cruelty with the last survivors, forcing themselves on them.

âGo on, take me, that'll be a change from a cabin boy's arse. And don't say no, or else guess where the hook of my stick'll be going.'

On the bridge, their cuckolded husbands were getting drunk. When they had consumed their fill of wines and brandy, they downed a whole chest of medicines, which killed some and sent the others into convulsions. The sky was filled with an apocalyptic tangle of cries. On the beach, Thunderflower witnessed all this without getting involved. It's not my area of expertise, she thought. But she watched with relish as a bottle that had escaped from the wreck floated towards her, and she grasped hold of it. How well arranged life is: on the litre bottle filled with white powder, the girl from Plouhinec recognised the label, which was like the one on the tiny vial bought in the pharmacy at Pontivy. As Viltansoù came back on to the sand with his arms full of

boxes, she asked, âCan you read, Yann? What's written on here?'

âThere? Arsenic.'

âReusenic'h?

Why were they travelling with that?'

âIn the bowels of a ship, what people fear most is rabbits or rats, which could gnaw at the wood of the holds and sink them in the middle of the ocean. And that

would

be a shame â for us! Come on, throw that useless thing away and come and help yourself from the wreck as well.'

Thunderflower placed the bottle upright snugly between her lovely rounded breasts.

âI've got

my

trophy already.'

Then as Viltansoù, raising his eyes, neared her pile of oranges on his way back to the ship, she put her order in as if he were going to the grocer's: âIf there's any sugar, bring me some.'

Â

Thunderflower was making jam. On the previous evening, Yann had found sugar (brown, to the Morbihan woman's amazement) and had also brought back a cask of rum â an alcohol of whose existence Hélène Jégado had been unaware. She poured a little of it over the deseeded citrus fruit quarters and the zest, boiling in cane sugar and water.