The Pope and Mussolini (11 page)

Read The Pope and Mussolini Online

Authors: David I. Kertzer

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Europe, #Western, #Italy

While

La Civiltà cattolica

would continue to denounce episodes of Fascist violence aimed at Catholic organizations, it would never again denounce Mussolini or Fascism. Quite the opposite: the journal would work on the Vatican’s behalf to legitimate Fascism in the eyes of all good Catholics, in Italy and beyond.

23

––

THE POPE

’

S NEWFOUND HOPES

for Mussolini got a further lift when the prime minister concluded his first address to parliament by asking for God’s help; no Italian government head since the founding of modern Italy had ever let the word

God

out of his mouth. Secretary of State Gasparri also saw grounds for hope. “Providence makes use of strange instruments to bring good fortune to Italy,” he told the Belgian ambassador: Mussolini was not only a “remarkable organizer” but a “great character.” Admittedly, the new prime minister knew nothing of religion, Gasparri added with a chuckle: Mussolini thought all Catholic holidays fell on Sundays.

24

Pius XI set out the goals for his papacy in his first encyclical,

Ubi arcano

, in December 1922.

25

He lamented attempts to take Jesus Christ out of the schools and out of the halls of government. He bewailed women’s lack of propriety in “the increasing immodesty of their dress and conversation and by their participation in shameful dances.” The notion that, in turning away from the Church, society was advancing, he warned, was mistaken: “In the face of our much praised progress, we behold with sorrow society lapsing back slowly but surely into a state of barbarism.” He stressed the importance of obedience to proper authority and took up Pius X’s program of battling “modernism.” He belittled the new League of Nations, on which so many in Europe were pinning their hopes for peace: “No merely human institution of today can be as successful in devising a set of international laws which will be in harmony with world conditions as the Middle Ages were in the possession of that true League of Nations, Christianity.” The pope’s plan was to bring about the Kingdom of Christ on earth. At heart, it was a medieval vision.

26

Mussolini was meanwhile sketching out his own authoritarian plan. “I affirm that the revolution has its rights,” he said in his opening speech to parliament. “I am here to defend the blackshirts’ revolution and to empower it to the maximum degree.… With three hundred thousand armed young men throughout the country, ready for anything

and almost mystically ready to carry out my orders, I could have punished all those who have defamed and tried to sully the name of Fascism.”

27

In late December, Mussolini convened the first meeting of the Grand Council of Fascism, which was responsible for addressing the most important issues of government policy and party organization. The following month the council approved the transformation of the sundry Fascist militias into the Voluntary Militia for National Security. These units had previously been the creatures of the local Fascist bosses; now Mussolini was eager to wrest control from them. Unlike the regular military, which swore allegiance to the king, members of the militia swore allegiance to Mussolini.

28

He moved quickly to make good on his promises to the Vatican, eager to show that he could do what the Popular Party had been incapable of doing. He would restore the privileges that the Church enjoyed before Italian unification. He ordered crucifixes to be placed on the wall of every classroom in the country, then in all courtrooms and hospital rooms. He made it a crime to insult a priest or to speak disparagingly of the Catholic religion. He restored Catholic chaplains to military units; he offered priests and bishops more generous state allowances; and to the special delight of the Vatican, he required that the Catholic religion be taught in the elementary schools. He showered the Church with money, including three million lire to restore churches damaged during the war and subsidies for Church-run Italian schools abroad. In cities and towns throughout the country, in the course of Mussolini’s many triumphal visits, bishops and local parish priests were encouraged to approach him to ask for funds for church repair. To further burnish his Catholic credentials, later in 1923 he had his wife Rachele and their three children—Edda and two sons, Vittorio and Bruno—baptized. Rachele, more principled in her anticlerical faith than her husband, went only reluctantly. Raised in the heart of red rural Romagna, she had learned early to despise priests and the wealth and power of the Church.

29

Because many Italians and foreign observers were uncertain what to

make of Italy’s new leader and his violent Fascist movement, Vatican approval played a major role in legitimizing the new regime. In widely quoted remarks, Cardinal Vincenzo Vannutelli, dean of the College of Cardinals, praised Mussolini as the man “already acclaimed by all Italy as the rebuilder of the fate of the nation according to its religious and civil traditions.”

30

Mussolini was eager to cement his growing bond with the Vatican by meeting with its secretary of state, Cardinal Gasparri. Like him, Gasparri came from a humble background. “I was born May 5, 1852 in Capovallazza, one of the hamlets that form the Town of Ussita,” Gasparri recalled in his typed memoir, “in the middle of the Sibillini mountains, about 750 meters above sea level. Clean air, enchanting view, healthy, hard-working, honest people, with large families, and the Gasparri families were most prolific of all.” His parents had had ten children, of whom he, the last, was naturally the favorite. While his nine siblings were “especially robust and lively,” he reflected, “I was frail, rather sickly, so that some predicted, and perhaps augured, that my life would be short, much to Mamma’s displeasure.” While his father spent many nights sleeping with the sheep in the pastures, little Pietro provided the family entertainment. As they huddled by the warmth of the fireplace, he read them stories of the saints. They all cried together as he recounted the terrible trials faced by the Church’s martyrs. “Mother had the gift of tears, transmitted to all the children, especially to me.”

31

Gasparri’s rendezvous with Mussolini had to be arranged with great care, for the Vatican secretary of state could not be seen meeting with the government’s head—the Holy See still did not recognize Italy’s legitimacy. The secret meeting was arranged by Gasparri’s old friend Carlo Santucci. Part of an aristocratic family close to the popes, he had been one of the first members of the Popular Party to break off to support the Fascists. His home had a valuable feature: it was in a corner building that had entrances on two different streets.

On January 19 Mussolini arrived in a car with his chief of staff, who would wait outside the building while the prime minister went in. Mussolini entered through one door, where he was greeted by Santucci’s father; the cardinal entered through the other, where Santucci’s mother welcomed him.

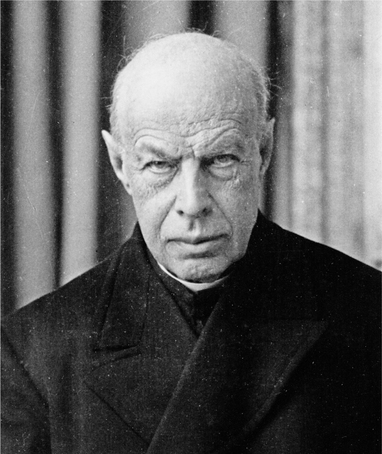

Cardinal Pietro Gasparri, Vatican secretary of state, 1914–30

The key issue on Cardinal Gasparri’s mind that day was not whether the Vatican would be willing to help end Italy’s democracy, for the Vatican had no particular fondness for democratic government. Rather, the question was whether Mussolini could be trusted to honor his promise to restore the Church’s influence in Italy and how likely it was that, with Church support, he could succeed.

32

For Mussolini, the former

mangiaprete

, or priest-eater, as he had been known in his earlier years, the stakes were high. If he could be the man to restore harmony between church and state, if he could win the pope’s blessing for his government and bring the conflict between them to an end, he would succeed where his predecessors had all failed. He would be a hero throughout the Catholic world.

For an hour and a half, the two men met alone. When Gasparri left, he paused to tell Santucci how pleased he was with the meeting, calling Mussolini “a man of the first order.” Mussolini rushed out the other door without saying a word. In the car, his chief of staff was eager to hear what had happened. “We must be extremely careful,” Mussolini told him, “for these most eminent men are very shrewd. Before entering very far into even preliminary discussions, they want to be sure our government is stable.”

33

The two men did make one decision that day: they agreed on a confidential go-between, a person whom both the pope and Mussolini would trust to convey their messages on the most sensitive matters.

It is not entirely clear how the sixty-one-year old Jesuit Pietro Tacchi Venturi came to be the choice.

34

He was born in 1861 to a prosperous family in central Italy; his father, a lawyer, proudly kept the rifle he had used in 1849 in helping defeat Garibaldi’s forces and retake Rome for the pope. Pietro went at an early age to study for the priesthood in Rome, then newly annexed to the Italian kingdom. In 1896 he began writing the official history of the Jesuit order and spent much of the next two decades in research that took him to libraries, archives, and monasteries across Europe. He published the first volume in 1910. During the Great War, Włodzimierz Ledóchowski, the Jesuit superior general, a Pole from the Austrian Empire, was forced out of Italy as an enemy alien. Tacchi Venturi, who had been appointed secretary general of the order in 1914, was left in charge of the Jesuits’ activities in Rome.

35

“Lean and severe,” as one of Tacchi Venturi’s colleagues described his appearance, he looked the part of the austere Jesuit. His baldness produced the effect of an oval face; his pointed ears set off against the fringe of gray hair on the back of his head. Clad in black clerical gown and white collar, he exuded seriousness and intensity.

36

Achille Ratti first met the Jesuit scholar in 1899, when one of Tacchi Venturi’s research trips brought him to the Ambrosiana Library.

37

Mussolini had apparently first heard of him from his brother, Arnaldo, who became friendly with the Jesuit during the months he spent in Rome during the war.

38

Then shortly before his secret meeting with Gasparri, Mussolini had met Tacchi Venturi. Within weeks of coming to power, Mussolini realized that one of the easier things he could do to ingratiate himself with the pope was to give the Chigi library to the Vatican. The government had purchased Palazzo Chigi—then as today the Italian prime minister’s headquarters—in 1918. With the building came its private library, begun by the seventeenth-century pope Alexander VII, which included three thousand old manuscripts and thirty thousand books. Achille Ratti, then Vatican librarian, had heard that the government was purchasing the building and tried unsuccessfully to acquire the library. In response to Mussolini’s offer to donate it, the Vatican sent Tacchi Venturi to evaluate the collection. Hearing one day that the Jesuit was in the building and perhaps recalling that his brother had spoken well of him, Mussolini sent word that he should come to his office to meet him. As it turned out, that encounter in late 1922

would be the first of many, many meetings between the Jesuit and Mussolini over the next two decades.

39

Pietro Tacchi Venturi, S.J

.

THE EARLY DISCUSSIONS DID

little to stop Fascist violence against priests and Catholic activists suspected of Popular Party sympathies. Three weeks after Mussolini became prime minister, the bishop of the northeastern city of Vicenza publicly denounced the latest attacks on local priests and proclaimed that perpetrators would be excommunicated.

40

In Ascoli Piceno, in the mountains east of Rome, a Fascist squad accosted a priest who edited a local paper and forced him to drink a liter of castor oil.

41