The Pope and Mussolini (61 page)

Read The Pope and Mussolini Online

Authors: David I. Kertzer

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Europe, #Western, #Italy

ON MARCH 15, THREE DAYS

after the papal coronation, the German army seized the rest of Czechoslovakia. In Prague the next day, Hitler proclaimed the country a protectorate of Germany.

36

Few could deny that Europe was about to endure another terrible war.

The day after the Führer’s triumphant speech from Prague, Ciano had his first meeting with the new pope and was pleased to find him unchanged, “benevolent, courteous, and human.” Pius XII expressed his concern about the German situation but told Ciano he planned to take a more conciliatory approach to the Reich and hoped to see an improvement in the Vatican’s relationship with Berlin. If these efforts were to be successful, he observed, the Nazi government would have to do its part. Ciano, happy to hear all this, expressed his belief that Mussolini could help persuade Hitler to cooperate. As for the Vatican’s recent dispute with the Italian government, the new pope “declared himself optimistic,” wrote Ciano. He promised to remove Cardinal Pizzardo

as head of Catholic Action and entrust its direction to a committee of diocesan archbishops. Mussolini had long wanted Pizzardo dismissed, but Pius XI would never agree to it.

The Vatican had recently asked Italy’s bishops if any tensions remained between Catholic Action groups in their diocese and local government or Fascist Party officials. The replies came in during the weeks after Pius XI’s death. With the notable exception of Milan, where Cardinal Schuster reported difficulties, the picture was hopeful. Virtually all reported excellent relations. The new pope did his part, instructing Dalla Torre to avoid publishing anything in

L’Osservatore romano

that either the Italian or the German government would find “irritating.” For Mussolini and all those who sought a return to the happy days of collaboration between the Vatican and the Fascist regime, it was as if a dark cloud had lifted.

37

C

HAPTER

TWENTY-NINE

HEADING TOWARD DISASTER

O

N GOOD FRIDAY, APRIL 7, MUSSOLINI SENT ITALIAN TROOPS INTO

Albania. The new pope, under international pressure to denounce the invasion, said nothing. “Not a word from his mouth about this bloody Good Friday,” complained one prominent French Catholic intellectual.

1

Italy’s ambassador to the Holy See was much relieved by the new atmosphere in the Vatican. “It is now clear,” Pignatti told Ciano two weeks later, “what peace it is that Pius XII is invoking for humanity. It is not the peace of Roosevelt, but rather that of the Duce.”

2

The contrast between the two popes was clear to all who knew them. The American reporter Thomas Morgan, who spent years in Rome and had often met both men, described the two as opposite in temperament. While Pius XI was “gladiatorial, defiant, commanding and uncompromising,” his successor was “persuasive, consoling, appealing and conciliatory.” Or as the French ambassador Charles-Roux put it, a mountaineer from Milan was succeeded by a Roman bourgeois; a man quick to speak his mind was succeeded by a cautious diplomat.

3

The Nazi government, too, was pleased by the new pope’s attempts to repair the damage done by Pius XI. In his memoirs, Ernst von

Weizsäcker, the head of the German Foreign Office who would soon succeed Bergen as German ambassador to the Holy See, wrote, “If Pius XI, so impulsive and energetic, had lived a little longer, there would in all likelihood have been a break in relations between the Reich and the Curia.”

4

But as it was, for Hitler’s birthday, on April 20, the papal nuncio in Berlin personally gave the Führer the new pope’s best wishes. Throughout Germany church bells rang in celebration. The German newspapers were full of praise for Pope Pacelli, lauding him for warmly congratulating Franco and his compatriots on their conquest of Spain. The papers drew special attention to the pope’s remarks equating Communism with democracy. In reporting all this to Ciano, the Italian ambassador in Berlin remarked that the new pope had come at an opportune

time. As the world was condemning the Nazis’ invasion of Czechoslovakia, the Reich needed, “perhaps for the first time, to have the Church with it and not against it.”

5

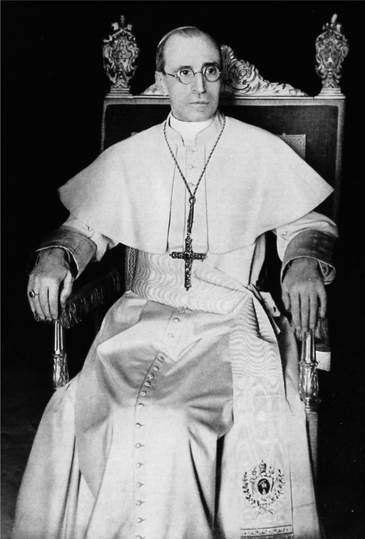

Pope Pius XII, March 1939

In May the pope met with Giuseppe Bottai, Italy’s minister of education and one of the men closest to Mussolini. Although the room was the same that Pius XI had used, Bottai was struck by how different it seemed. Early in his papacy, Pius XI had kept a spartan office, but as he aged he increasingly accumulated mementoes as well as oft-consulted tomes. As Bottai described it, the elderly Pius XI had been surrounded by a “picturesque disorder of furniture, ornaments, knick-knacks, papers, newspapers, books.” In contrast, Pius XII sat amid a “meticulous order.” His desk held only a few indispensable objects. Most of all, compared to the voluble, excitable Pius XI—certain that God was guiding him, apt to go off on tangents—his successor exuded a sense of calm and the air of someone who knew his job.

6

Over the next months, Mussolini became more confident that a new, happier era had arrived. Among the various bits of good news he received was the pope’s decision, in July, to reestablish relations with the right-wing Action Française. In response to a request from its leader, Charles Maurras—protofascist and France’s foremost anti-Semite—the pope reversed Pius XI’s 1926 ban on Catholic participation in the organization. The move angered not only the French government but also many of France’s most influential clergymen.

7

Pius XII, Pignatti reported, was not only a conservative but “has a clear sympathy, I would almost say a weakness, for the nobility, which is in his blood.” Roman nobles were delighted. His predecessor, coming from a modest social background, had shown little deference to them and over the years cut back on their privileges. Pius XII, a product of the black aristocracy, moved quickly to reintroduce their old prerogatives.

8

Mussolini got another encouraging report about the new pope, this one from Switzerland. His ambassador there had spoken at length with the papal nuncio, recently returned from Rome. The atmosphere in the Vatican, the nuncio reported, was “completely changed,” like a “breath

of fresh air.” The Holy Father spoke “with much sympathy for Fascism and with sincere admiration for the Duce.” He was convinced that his reorganization of Catholic Action in Italy would remove a major source of tension with the regime. As for Germany, the new pope could not be more eager to come to an agreement.

9

Many in the Church were also pleased by the change. After years of the stubborn, combative Pius XI, they found audiences with Pius XII a relief. In contrast to Pius XI’s long-winded monologues, the new pope listened carefully to his visitors and never seemed to forget anything they told him. Like Pius XI, the new pope followed the tradition of taking his meals alone. They were if anything even simpler than his predecessor’s, and as he ate, he enjoyed watching his canaries flutter in the birdcage he kept in the dining room. But Pius XII readily agreed to pose for photographs with small visiting groups, something Pius XI thought beneath his dignity, and unlike Pius XI he was happy to use the telephone. “Pacelli here,” Francis Spellman was startled to hear when the new pope decided to call his old friend, recently appointed archbishop of New York.

10

After the tensions of the last months of Pope Ratti’s life, all the elements of the clerico-Fascist regime soon returned. Emblematic was a ceremony held at one of Rome’s major churches in April 1940. The national Fascist girls’ association had long been campaigning, under the guidance of the priests attached to their local groups, to make Saint Catherine Italy’s female patron saint. The girls got their way shortly after Pacelli became pope, and to mark the first celebration of the new national holiday, the bishop overseeing the Fascist girls’ association presided over a special mass. Each of the two thousand girls there carried a white rose that, one after another, they deposited at the church altar.

11

But the normal pleasures of life in Rome were about to give way to the realities of war. Early on the morning of September 1, 1939, German troops invaded Poland. They imprisoned or murdered many Catholic priests, but the pope confined his remarks to a generic appeal for peace and brotherhood. He did not want to take sides, not least

because of a belief that the Nazis were likely to win.

12

Two days later Britain and France declared war on Germany. The next month, under the supervision of Adolf Eichmann, German forces began to deport Jews from Austria and Czechoslovakia to camps in Poland. The Second World War, and the Holocaust, were under way.

In the spring of 1940, German armies were marching from conquest to conquest. Eager to share in the spoils, on June 10 Mussolini declared war on France and Britain. He rushed Italian forces into southern France to grab territory before Nazi troops seized everything for themselves. In their enthusiasm, many Italians thought the war would be short. Tacchi Venturi predicted it would be over by Christmas.

13

Italy’s Jews lived lives of desperation, vilified as enemies of the state, thousands out of work, their children forced from the schools. To build support for its anti-Semitic campaign, the government continued to rely heavily on Catholic imagery, citing Church texts. The government’s main vehicle for spreading its anti-Semitic bile remained the twice-monthly, color, glossy

La Difesa della razza

. Much of its content was cannibalized from Catholic anti-Semitic materials. A typical issue, in April 1939, published an article titled “Christ and Christians in the Talmud,” and another “Catholics and Jews in France.” Articles such as “The Eternal Enemies of Rome” told readers that the Church had always treated Jews as second-class citizens in order to protect Catholics from their predation. The enemy for

La Difesa della razza

, as for the Holy See, was the French Revolution, cast as the work of a liberal, Masonic, Jewish conspiracy.

14

Mussolini again began to make use of Father Tacchi Venturi. Two weeks after the new pope’s coronation, the Duce summoned the Jesuit to convey the message that he wanted the pontiff to direct Spain’s Catholic clergy to support Franco even more strongly than before.

15

He also wanted the pope’s help in getting priests in Croatia to encourage the faithful to support Italy rather than Germany; and he asked the pope to mobilize the Catholic clergy in Latin America to combat pro-United States sentiment there.

16

Meanwhile, the Vatican-supervised

La Civiltà cattolica

was drumming up Catholic support for the racial laws. In November 1940 the journal praised a new government-published book that explained Italy’s brand of racism and compared its racial campaign favorably to Germany’s. Italy’s campaign loyally followed Catholic teachings, while Germany’s relied on specious biological theories. When the former head of the University of Rome, a Jew who had converted to Catholicism, wrote to the Vatican secretary of state to complain about the article, Monsignor Tardini wrote back defending it.

17

THE FATE OF ITALY

’

S

troops soon showed the hollowness of Mussolini’s saber rattling. Poorly equipped, poorly led, and poorly trained, Italian soldiers proved incompetent. Emblematically, within three weeks of Italy’s declaration of war, Italo Balbo, Fascist aviator extraordinaire, died when an Italian antiartillery unit mistakenly shot down his plane as he was landing at an Italian airfield in Libya.