Read The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere Online

Authors: Caroline P. Murphy

Tags: #Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #History, #Renaissance, #Catholicism, #16th Century, #Italy

The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere (3 page)

Despite Erasmus’s view of him, Julius’s behaviour was no worse, and in fact much better, than that of many of his colleagues. This was the period in which the Catholic Church was at its most magnificent, and also at its most corrupt. Sexual activity was only one abuse among several committed by the clerical elite, and few in Italy commented adversely on such conduct. Only occasionally did men such as the anti-clerical Roman lawyer Stefano Infessura write in his diary in

1490

that the life of a Roman cleric ‘has been debased to such an extent that there is almost not one who does not keep a mistress, or at least a common prostitute’.

8

It is impossible to count the number of children who called cardinals their fathers in fifteenth-century Rome. Those that are recorded – such as the children of Pope Alexander VI, the infamous Borgia pope, or his immediate predecessor, Innocent VIII – are known because their fathers became popes.

9

Both these popes, who had fathered their children when they were cardinals, openly acknowledged them. As cardinals they had led lavish, decadent lives. They were as much playboys as ecclesiastics.

Such a way of life interested Giuliano della Rovere less than it did his colleagues. In Avignon he worked hard, with variable success, as a papal diplomat. Then in February

1482

he returned to Rome, and his life changed. If Giuliano was still playing second fiddle in Sixtus’ affections to his young cousin Raffaello, his standing at the Vatican court did, none the less, improve. He received additional bishoprics, including those of Pisa and the Roman port of Ostia, and he began to acquire a greater number of friends and allies in the College of Cardinals.

Giuliano’s new status in Rome led him to relax to some extent, even to imitate the lifestyles of his cardinal friends. At any rate, some time after he returned to Rome, he met a young woman named Lucrezia. If he did not actually fall in love with her, he was sufficiently attracted to her to break his vows of celibacy. Unwittingly or not, Julius was to add fathering a child to his earthly legacy.

chapter 2

It is rare for much to be known about the life of cardinals’ concubines, and it is only through a certain amount of teasing out of the available evidence that Giuliano’s mistress, Felice’s mother, comes to life. In later histories of the popes, Lucrezia’s surname is given as Normanni, which makes Felice’s matrilineal line particularly interesting, and in fact more venerable than that of her father.

1

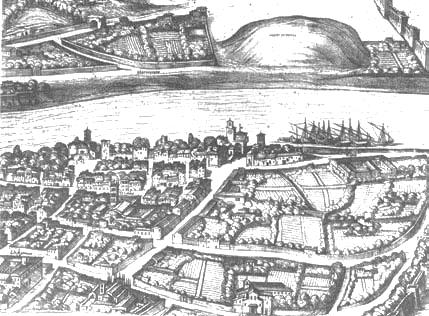

The Normanni formed one of the oldest Roman families; their name indicates they could trace their roots back to the eleventh-century Norman invasion of Italy and the sacking of Rome. They lived in fortified palaces on the opposite side of the Tiber from the main part of the city of Rome, in the area known as Trastevere, and were allies of that district’s most bellicose clan, the Pierleoni. That Lucrezia came from Trastevere is itself significant.

2

This was the same district in which the Ligurians – the Genoese and the Savonese

– resided. Although Cardinal Giuliano’s own palace was on the other side of the river, he visited compatriots in this part of Rome, which would have given him the opportunity to meet Lucrezia. Giuliano could have encountered her on the street, perhaps on the Via degli Genovesi, which runs through the heart of Trastevere. In the village-like atmosphere that still permeates old Trastevere, it would not have been difficult for him to track her down.

There were in fact several prominent women from the Normanni family, of whom the best known is Jacopa, born at the end of the twelfth century, and known as Jacopa dei Settesoli (seven suns). As a wealthy widow she became an extremely fervent supporter of St Francis of Assisi. She founded the first Roman seat for the Franciscans, the Ospedale di San Biagio, now the church of San Francesco a Ripa, in Trastevere, the centre of Normanni family terrain. The street leading up to the church is now called the Via di Jacopa dei Settesoli. St Francis called her ‘Brother’ Jacopa in praise of her fortitude, integrity and ability to live with manly austerity, and made her a kind of honorary friar. ‘Fra Jacopa’ is the name she chose to have inscribed on her burial tomb in Assisi.

3

Coincidentally or not, Felice would also possess similarly ‘masculine’ qualities to those of her illustrious ancestor.

However, over the centuries, like many of their counterparts who had held sway in Rome in medieval times, the Normanni family found its prestige and power declining as the city fell into chaos. By the end of the fifteenth century the Normanni were apparently of little account in the city. Yet even if the family was no longer wealthy, Lucrezia’s parentage means she was not a street girl, and it seems unlikely that she had become a courtesan, as they tended to be women who were not native to Rome. That Lucrezia came from a good family does not make her unusual as the choice for a cardinal’s sexual liaison: Vannozza Cattanei, who in the

1470

s and

1480

s was the mistress of Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia – the future Pope Alexander – and mother of Cesare, Joffre and Lucrezia, came from a similar background.

One does not know if Giuliano and Lucrezia had a lasting relationship or a brief encounter. Lucrezia might have been impressed by the compelling cardinal, the nephew of the Pope, and willingly acquiesced to his advances. It is also possible her impoverished family might have encouraged her to yield to him in the hope they would all benefit. Whatever the duration of the liaison, Felice was certainly the only fruit of this union to grow to adulthood.

chapter 3

The date of Felice’s birth is not known, so logic and common sense must play a part in its determination. Felice cannot have been born earlier than

1483

, because Giuliano did not return to Rome until late

1482

. And it seems unlikely that she was born any later because, by

1504

, she will be exhibiting a maturity and sense of self beyond that of a teenage girl.

From the perspective of Giuliano’s and Lucrezia’s child, it was vital that Giuliano should acknowledge paternity. Lucrezia was of sufficient standing that honourable arrangements were made for her following her pregnancy. The baby would not go to any of Rome’s convents or hospitals which took in foundlings, such as the Santi Quattro Coronati, or the Ospedale di Santo Spirito, the destination of many a cleric’s bastard child. Nor was her mother to live, shamed, as a fallen woman. Instead, she was married, probably either just before or soon after Felice’s birth, to a man named Bernardino de Cupis. While the indications are that the relationship between Giuliano and Lucrezia ended with the birth of Felice, the marriage kept both Lucrezia and her baby within the orbit of the della Rovere family. Bernardino was

maestro di casa

, the major-domo who ran both the household and the life of Giuliano’s cardinal cousin Girolamo Basso della Rovere. In contrast to his relationship with his Riario cousins, Giuliano was close to Girolamo. In

1507

, he paid for Girolamo’s magnificent tomb, sculpted by the Venetian artist Andrea Sansovino, in the della Rovere family church of Santa Maria del Popolo.

Of the little that is known about Lucrezia, it can be accepted that she was a loving mother. Felice, her half-sister Francesca and half-brother Gian Domenico were very fond of her. The four formed a tight-knit unit much later in life, valuing their family connection above other ties. That Lucrezia was allowed the opportunity to be a good mother to Felice is interesting in itself. It was not usual in Renaissance Italy for the mothers of the illegitimate children of the elite to be allowed to form a bond with their children, who were usually immediately absorbed into their father’s families. The mothers of the Medici bastards are completely unknown, including the mother of Giulio, the future Pope Clement VII. Duke Alessandro de’ Medici’s mother, a North African slave girl known as Simonetta, was later married to a mule-herder and vanishes from sight. Even though Vannozza Catanei, Lucrezia Borgia’s mother, established an identity in her own right as a substantial property-holder in Rome, she had little contact with her daughter. Rodrigo Borgia removed Lucrezia at a young age from her mother and placed her in the home of his new mistress.

If Felice, unlike many of her counterparts, had not spent her earliest years at her mother’s side, it is unlikely that she and Lucrezia would have been as close as they were when Felice was an adult. Felice had similarly strong relationships with her half-brother and half-sister, suggesting that the house Lucrezia ran was a happy one. As a wife, Lucrezia met with Bernardino’s satisfaction. He made her one of the outright heirs to his estate in his will of

1508

, an unusual act given that he had sons, suggesting that he thought well of her. She is referred to as ‘Magnifica Matrona’ (‘magnificent matron’), a title that attests to the position she had obtained in Rome, a long way from being a cardinal’s unwed teenage lover.

1

It is also probable that it was Lucrezia rather than Giuliano who gave their daughter her name. Felice, pronounced ‘

feh-leee-chay

’ in Italian, is a girl’s name sometimes used in the English-speaking world today, pronounced with a soft

c

. But in Italy, then as now, it is a boy’s name. A girl should more correctly have been called Felicia or Felicità. The word ‘

felice

’ means lucky, fortunate, happy. As a name indicative of a situation, it might be chosen by a mother in Lucrezia’s position rather than by a cardinal father. In this instance, the name Felice could well refer to the circumstances of the baby girl’s birth. She might, for example, have survived a difficult delivery. Or perhaps her name refers to the fortunes of mother and child. A pregnant young mother, banished from her family home, could easily have been obliged to place her child in an orphanage. Instead, Lucrezia’s daughter had a lucky start in life, and Lucrezia herself had what she saw as a fortunate new beginning.

chapter 4

It was common practice for male members of the elite to make honest women of their mistresses by marrying them off to high-ranking servants or those loyal to the family. Cecilia Gallerani, the mistress of Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, immortalized by Leonardo da Vinci as

The Lady with an Ermine

in

1491

, was married a year later to a Sforza associate, Count Ludovico Carminati de Brambilla. Rodrigo Borgia arranged for Vanozza Cattanei first to marry Domenico d’Arignano, and then, on the death of this first husband, Giorgio della Croce. Both of these men were apostolic secretaries at the Vatican Palace. To accept such a bride meant that these men were assured the gratitude of their wives’ powerful former (and sometimes continuing) lovers, and could expect attendant benefits. Nor did they necessarily have to have anything to do with the children that were not their own, if these children were not actually raised by their mothers.