Read The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere Online

Authors: Caroline P. Murphy

Tags: #Social Sciences, #Women's Studies, #History, #Renaissance, #Catholicism, #16th Century, #Italy

The Pope's Daughter: The Extraordinary Life of Felice Della Rovere (5 page)

The Roman families made a lot of money, often legally, from the collection of tolls to cross bridges or to pass in and out of sanctioned areas, such as the Jewish ghetto. But by the turn of the fourteenth century gang warfare had escalated to such an untenable degree that no one was safe in the streets. In

1308

members of the Church, especially the non-Italians, took the opportunity to canvass moving the seat of the papacy from Rome to the more peaceful city of Avignon, in southern France. Their case was reinforced by a great fire that rendered the papal palace at the Lateran uninhabitable. It is certainly possible that it was deliberately set by the French in order to hasten the departure to Avignon.

Exile from Rome lasted almost a century, until the election of Pope Martin V. As the former Oddo Colonna, a member of the important Roman family, Martin wielded sufficient influence to negotiate a return of the papacy to a more peaceful Rome in

1420

. He is credited not only with returning the papacy to Rome but with bringing the Renaissance to the city as well. Fifteenth-century Rome still had more in common with postwar, twentieth-century Beirut than it did with prosperous fifteenth-century Florence. There were still vast no-go areas in the city, made dangerous not only by lawlessness but also by the swampy, malaria-ridden terrain that needed to be drained before it could be inhabited. Scores of buildings had been abandoned, their residents having fled the turbulent times or succumbed to outbreaks of the plague. Other structures had been rendered uninhabitable by an earthquake in

1349

. Even as late as

1413

, only seven years before the return of Martin V, King Ladislas of Naples had taken advantage of Rome’s weakened state to invade and plunder the city. The main streets were almost impassable, access to St Peter’s near impossible. A city uninviting to pilgrims, who might otherwise have come to venerate the bones of St Peter, was denying itself a valuable economic resource.

But what the troubles of the previous century had done was to undermine the power of many of the Roman families responsible for the initial disruption. The Pierleone, the Normanni and the Frangipane lost a great deal during the fourteenth century, and they never really recovered from the changed financial situation. The Colonna and the Orsini, however, wealthy by virtue of all the land they owned in the Roman countryside, retained and even consolidated their footing as Rome’s first families. Although this strengthened the rivalry between them, members of the families who had become clergymen were particularly committed to restoring the city their ancestors had helped to destroy.

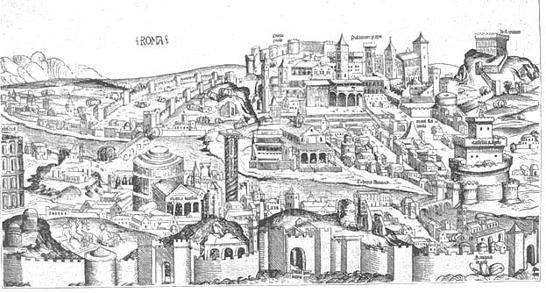

Fifteenth-century commentators on Rome provide accounts of the disrepair into which the city had fallen: ‘In the absence of the Pope Rome had turned into a cow pasture; sheep and cows were grazed where there had once been merchants’ stalls,’ wrote Vespasiano da Bisticci.

3

In

1443

a Florentine visitor, Alberto degli Alberti, wrote from Rome to Giovanni de’ Medici, to tell him, ‘The modern houses, those built of brick, are plentiful, but in disrepair. The beauty of Rome is its [ancient] ruins. The men that are now called Romans are in some way different in their bearing and habits from the ancients; to summarize, they all tend cows. Their women have beautiful faces, but they do not keep the other parts of their body very clean [not surprisingly, given the lack of recourse to water in the city].’

4

To return Rome to its former magnificence would be a challenge, and the labour of a century or more.

Yet under a succession of popes, commencing with Martin V, Rome experienced a radical transformation. The city underwent a rebirth, becoming a ‘Renaissance’ city in the truest sense of the word. Martin V began by reviving the old office of

maestro di strada

, which had been ‘neglected for a very long time’.

5

The tasks of the

maestri

were to supervise the clearing, repaving and restoration of the city’s streets and squares. They enforced restrictions such as preventing private dwellings encroaching on public streets or the construction of unauthorized buildings on the banks of the Tiber, and regulated the supply of water.

6

Eugenius IV, Martin’s successor in

1431

, had a rather more turbulent and consequently less productive papacy, yet even he succeeded in cleaning up the Piazza della Rotonda in front of the Pantheon. He removed the hermits who lived in the ancient temple as well as the sheds and shops that had sprung up around it. But it was Nicholas V and Sixtus IV, both Ligurians, who took the task of rebuilding Rome most seriously. Nicholas, who succeeded Eugene in

1447

, was arguably the first Renaissance pope for whom the encouragement of art and culture was more critical than the promotion of spirituality. As a student in Bologna, he had tutored the sons of wealthy Florentines and beaome aware of the extraordinary developments in their city. Nicholas, benefiting from a more tranquil Rome, was able to concentrate his energies on his vision of an ideal planned city.

7

Even if few of his ideas were carried out during his eight-year papacy, they were sufficiently well conceived to be put into effect by his successors. As the adviser for Nicholas’s new Rome, the Pope brought to the city the greatest architect, humanist and conceptual thinker of his day, the Florentine Leon Battista Alberti. In Rome, as the art historian Giorgio Vasari would write a century later, Alberti did ‘many useful things that are worthy of praise, the Acqua Vergine, which was broken, he fixed, and he made the fountain in the Piazza de Trevi, with those marble decorations that one still sees’.

8

Apart from the Tiber river, the fountain was Rome’s chief public source of water, and certainly the cleanest. Nicholas repaired the city’s walls and many of its churches and took advantage of the virtual gutting of the Lateran Palace to argue for the development of the papal palace on the Vatican hill, next to St Peter’s.

Nicholas produced a template for Roman reconstruction that his countryman Sixtus followed rigorously when he ascended the papal throne in

1471

. Sixtus’ propositions for urban planning were equally aggressive. He drew up the previously mentioned bull, the

Et si de cunctarum civitatum

, designed not only as a means of beautifying the city but also as a means of social engineering. The bull compelled ‘owners not occupying their houses to sell them to neighbours who do occupy, and who wish to rebuild their ruined houses for the sake of the appearance of the city’.

9

Bernardino de Cupis benefited from such a mandate as he expanded his property on the Piazza Navona. Sixtus was also responsible for the removal of the medieval porticoes along Rome’s streets, the kind that can still be seen in modern-day Bologna. The reason Sixtus gave for his plans was that they rendered the streets ‘so narrow that it is not possible to stroll through them conveniently’. However, the porticoes had made it very easy for Roman families to barricade their streets and homes in times of conflict, so for Sixtus it was another way to weaken the power of the native citizenry. Those that were not torn down were bricked up.

Sixtus also reconstructed the bridge across the Tiber, whose origins dated back to

12 bc

. The bridge, whose state of disrepair had earned it the name Ponte Rotto (broken bridge) became the Ponte Sisto, and is still in use today. The Ponte Sisto provided Sixtus’ Ligurian countrymen, who lived in Trastevere, with better access to the rest of the city, in particular the commercial districts. Sixtus also strengthened his own family identity by having the architect Baccio Pontelli rebuild the church of Santa Maria del Popolo, soon to become filled with della Rovere family tombs and chapels. A substantial social initiative was his reconstruction of the Ospedale di Santo Spirito, a hospital still in use as a medical centre. Patients were treated in wards whose walls are decorated with frescos commissioned by Sixtus in

1475

depicting significant events from his life.

10

Nor did the Vatican Palace, the new papal home, escape his attention. There he built a great new chapel, decorated with a star-spangled blue ceiling and pictures in the lower storeys by the most fashionable Florentine painters, such as Sandro Botticelli and Domenico Ghirlandaio. Despite the exceptional additions that were to be made by the Pope’s nephew Cardinal Giuliano later in his life, the chapel is still known as the Sistine Chapel. It was the first substantial demarcation of della Rovere identity at the Vatican Palace.

chapter 6

Even if by

1483

, the time of Felice’s birth, Rome was still some way from being the marvel of Renaissance Italy, Cardinal Giuliano’s daughter was born into a city filled with a new optimism and a sense of excitement. Moreover, Felice spent her childhood right at the heart of things. The Palazzo de Cupis became a social centre of the new Rome. It was constantly filled with the ‘Pope’s men’, apostolic secretaries, chamberlains,

maestri di strade

, and merchants and lawyers.

1

They spoke a language of their own, exchanged rumours and gossiped about events in the city, made deals, accepted bribes. A small girl did not necessarily understand the meaning of it all, but an intelligent one could recognize the importance of such activity. These were the men who made her city work. What Felice learned from her proximity to them had tremendous bearing on how she would later conduct her own life.

Equally important to Felice della Rovere’s development was that in Bernardino de Cupis’s circle she had her own worth. Her father, who had kept something of a low profile during the reign of his uncle Sixtus, achieved much greater prominence on Sixtus’ death in

1484

.

2

The new pope, Innocent VIII, was a fellow Ligurian. Giuliano della Rovere became his chief adviser, to the extent that Lorenzo de’ Medici was counselled by his ambassador to Rome to ‘send a good letter to the Cardinal of St Peter, for he is Pope and more than Pope’.

3

This meant, of course, that Rome came to regard Cardinal Giuliano in a newly respectful light. The Cardinal now held the key to the kinds of rewards and promotions that Bernardino’s associates lived for. By association, reverence was paid to his young daughter. One does not how know much Giuliano saw of Felice, but she knew she was his child, and everyone else knew it too. She was always Felice della Rovere, never Felice de Cupis. Other members of the della Rovere family in Rome treated her as one of their own as well. Her cousin Girolamo della Rovere, Bernardino’s employer, was sufficiently fond of her and perhaps generous to her that later Felice would name one of her sons Girolamo; so she clearly had good memories of him.

There is no doubt that Felice did spend her childhood in a loving and stable environment, often so fundamental to a child’s, and the subsequent adult’s, sense of self-belief. For Lucrezia, the child was her lucky one; the pair had a good life that might not necessarily have been theirs. For her stepfather Bernardino, she was a part of the family he served so devotedly. Nor did Felice lack for company of her own age; her half-sister Francesca was only two years younger. The girls might not have been allowed to play outside, but the Piazza Navona was an exciting place to watch from a window. They could look down on the bustle of its daily market, or at the pomp of the festive tournaments that were held at the beginning of the year. Moreover, Felice was special. For Lucrezia and Bernardino, illegitimacy did not make her inferior to the rest of the family. In fact, the reverse was true. She was a cardinal’s daughter, and the blood of a pope ran in her veins. If they behaved towards her any differently than they did towards her siblings, it was probably to be rather more respectful, perhaps more indulgent, because of who she was. In other words, her mother and stepfather treated her more as they might a favoured son than a normal daughter of the time. Consequently, Felice grew into adolescence secure in the love of those around her, confident of her own identity and perhaps somewhat wilful, certain that she would get her way in the end.

And then, in

1492

, Pope Innocent VIII died, and everything changed for Cardinal Giuliano and his daughter.