The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity (11 page)

Read The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity Online

Authors: Jeffrey D. Sachs

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Economic Conditions, #History, #United States, #21st Century, #Social Science, #Poverty & Homelessness

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau.

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau.

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau.

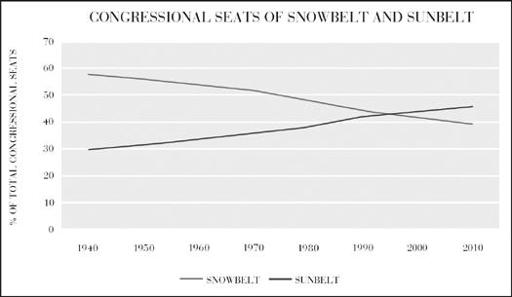

Suppose that Snowbelt voters support federal government social programs by a 70–30 margin, while Sunbelt voters oppose those programs by a 70–30 margin. To keep things simple, also suppose that there are 100 million voters in all, initially divided as 60 million in the Snowbelt and 40 million in the Sunbelt. Sixty percent of

congressional seats and hence (roughly) 60 percent of electoral votes will be in the Snowbelt and 40 percent in the Sunbelt. It’s easy to see that nationwide 54 percent of the voters support the social programs and 46 percent oppose them.

Suppose now that a random mix of 20 million northerners move to the Sunbelt. Of those migrants, 70 percent (14 million) support government social programs and 30 percent (6 million) oppose them. Assume as well that there is no change of political values among the 100 million Americans, so that a 54–46 majority nationwide continues to support the social programs. Nonetheless, with the new demography, Congress is now likely to vote down the programs. Here’s why.

In the “new” Sunbelt, there will now be 60 million voters. The “old” 40 million Sunbelt residents oppose government programs by a vote of 28 million versus 12 million. The “new” residents (who have arrived from the Snowbelt) support government programs by a margin of 14 million to 6 million. In total, therefore, 34 million voters of the new Sunbelt (57 percent) will oppose government social programs and 26 million (43 percent) will support them.

The South will still be a majority anti-government region, though less decisively than before the in-migration from the North. Yet now it will command

a majority of seats in Congress

and in the Electoral College and will elect an anti-government majority to Congress and the presidency. Even though there is no change in national opinion (which is still a majority in favor of the social programs), the rise of the Sunbelt population by itself is enough to shift Washington from a pro-government majority to an anti-government majority. Demography is not quite destiny, but it plays a major role.

9

Sunbelt Values

With the rise of the Sunbelt came new and deep cultural cleavages in American politics. Well before the 1960s, state and local politics

in the South had long resisted a large role of government in the local economy. After all, this was the home of “states’ rights” and the losing side of the Civil War. Moreover, the anti-Washington sentiment was a reflection of the long-standing traditional resistance of southern white voters to funding public goods in a population with a significant African American minority. With the rise of the Sunbelt, that anti-government fervor gained weight, indeed an effective majority, in national politics. Anti-Washington sentiments came easy to a region that had long harbored deep historic resentments against the federal government, sentiments newly stirred by the civil rights movement, immigration, and the cultural upheavals of the 1960s.

The South is also the bastion of fundamentalist Christianity: 37 percent of southerners count themselves as evangelical Protestants, and 65 percent are Protestants, including mainline and evangelical denominations.

10

This compares with just 13 percent of northeasterners who count themselves as evangelical Protestants and 37 percent as Protestants of any denomination. With Sunbelt presidents backed by powerful evangelical constituencies, the evangelical cultural agenda—right to life, prayer in the schools and other public facilities, anti–birth control, anti–gay marriage, antievolution school curricula, and so forth—came to national prominence and supercharged the country’s cultural cleavages.

The culture wars opened on many fronts. In addition to the civil rights movement, urban riots, and rising crime rates, the 1960s had ushered in the counterculture of drugs, sexual liberation, the surge of women’s rights, and the beginning of gay rights. The cumulative effect of these cultural upheavals, packed into just a few years and capped by increasingly intrusive social regulation such as cross-city busing, affirmative action, and Supreme Court–led legalization of abortion in 1973, led to a sense among religious conservatives that liberals aimed not just to fight poverty and discrimination but also to dictate a new social order. The culture pot was set boiling. Sunbelt conservatives rose up against an activist federal government that they believed threatened traditional Christian values.

Suburban Flight

The civil rights era and racial unrest in the cities in the 1960s also accelerated another massive geographical trend: the flight to the suburbs by affluent white households. Suburbanization was already under way in the 1950s, before racial politics came to the forefront. The rise of the automobile, combined with the postwar baby boom and the return to normalcy in the 1950s, spurred the surge in suburbanization. Then came a dramatic white flight to the suburbs in the 1960s and afterward, reflecting both social and economic forces. The social forces consisted mainly of the desire of many whites to live in homogeneous white neighborhoods. The economic forces consisted mainly of the search by affluent (and mainly white) households for quality schooling for their children.

11

More affluent households increasingly sorted themselves into higher-priced affluent suburbs that supported better public schools based on higher tax collections. The influx of affluent households into favored suburbs raised property prices and priced out working-class households, which had to choose among less desirable urban and suburban locations. The poor were generally left to the low-rent and least desirable locations in the inner cities. Thus, Americans sorted themselves by class and race to produce today’s residentially divided America.

The economic ramifications of the suburban-urban divide were stark, in that school financing diverged between poor inner cities and affluent suburbs. Residential sorting became a crucial way in which educational and income inequalities were propagated from one generation to the next. In order to avoid a prolonged poverty trap, federal and state financial support for very poor school districts became more important than ever.

The political ramifications were equally stark: the affluent suburbs turned more Republican, and the poorer urban areas turned more Democratic. Congressional districts thereby became “safer” for Republicans or Democrats, with fewer swing districts as a result.

In the safe districts, dominated by one of the political parties, the real political competition comes not in the November elections but during the primaries, tending to pull the Republicans in safe districts more toward the right and the safe Democrats more toward the left. We should remember, though, that big corporate money has pulled both parties to the right. The overall effect is a very conservative Republican Party and a Democratic Party that is generally centrist (or even right of center in districts where campaign financing looms especially large).

Still a Consensus Beneath the Surface

One possible reading of this chapter is that the search for a new economic consensus in America is a fool’s errand. After all, the country is deeply riven by cultural, geographical, racial, and class differences, all of which have become deeper in recent decades. The Tea Party seems to represent the latest ratcheting up of the ongoing battles between liberals and conservatives, northerners and southerners, whites and minorities. How, in these circumstances, can there possibly be a new set of shared values? I think this view of a nation in a fundamental and irreconcilable divide is wrong. There is much more consensus than meets the eye.

The real issue about consensus is not whether Americans can agree on everything important to their lives—clearly the answer to that is no—but whether Americans can agree on a set of national economic policies to promote overall efficiency, fairness, and sustainability. Here, then, are some things on which Americans broadly agree.

They agree that there should be equality of opportunity for American citizens. They agree that individuals should make the maximum effort to help themselves. They agree that government should help those in real need, as long as they are also trying to help themselves. And they broadly agree that the rich should pay more in

taxes. These core values can form the basis of a broad and effective consensus on the basic direction of economic policy.

In 2007, the political scientists Benjamin Page and Lawrence Jacobs found that 72 percent of Americans agreed that “differences in income are too large,” and 68 percent rejected the notion that the distribution of income and wealth is fair.

12

Large majorities agreed that government “must see that no one is without food, clothing, or shelter” (68 percent); agreed that “government should spend whatever is necessary to ensure that all children have really good public schools they can go to” (87 percent); “favor own tax dollars being used to help pay for … early childhood education in kindergarten and nursery school” (81 percent); “favor own tax dollars being used to help pay for retraining programs for people whose jobs have been eliminated” (80 percent); and agreed that “it is the responsibility of the federal government to make sure that all Americans have health care coverage” (73 percent).

13

In the Page and Jacobs data, no less than 95 percent agreed with the general principle that “one should always find ways to help others less fortunate than oneself.” The proportion agreeing with the proposition that government “should redistribute wealth by heavy taxes on the rich” climbed from 35 percent in 1939 to 45 percent in 1998 to 56 percent in 2007. It is plausible that the realities of America’s massive increase in income inequality have contributed to the rising sentiment for redistributive taxation.

Such egalitarian views have recently been confirmed in surveys by the Pew Research Center.

14

Eighty-seven percent agreed that “our society should do what is necessary to make sure that everyone has an equal opportunity to succeed.” Sixty-three percent concurred that “it is the responsibility of government to take care of people who can’t take care of themselves.” Yet, as always, primary responsibility in America is pushed back to the individual. Only 32 percent agreed that “success in life is pretty much determined by forces outside of our control,” and only 33 percent subscribed to

the view that “hard work offers little guarantee of success.” In the American ethos, the government should help when necessary, but the individual can and should remain the principal author of his or her own fate.

The flip side of the view supporting public responsibility toward the poor is an equally strong consensus that big business has been allowed to run away with the prize. Though the public overwhelmingly recognizes the importance of private business to the economy, it also overwhelmingly concurs that “there is too much power concentrated in the hands of a few big businesses” (77 to 21 percent in April 2009) and that “business corporations make too much profit” (62 to 33 percent in April 2009).

15

There is also a consistent public majority in favor of raising tax rates on the rich.

Surveys have also shown a continuing high importance accorded to the natural environment. Americans are environmentally conscious, even if their federal government is not. In the Pew survey, 83 percent of Americans agreed that “there needs to be stricter environmental laws and regulations to protect the environment.”

16

In June 2010, a

USA Today/Gallup

poll found that by a margin of 56 to 40 percent, Americans favor legislation to “regulate energy output from private companies in an attempt to reduce global warming.” An ABC News/

Washington Post

poll similarly found that by a margin of 71 to 26 percent, Americans agree that the federal government should “regulate the release of greenhouse gases from sources like power plants, cars and factories in an attempt to reduce global warming.”

17

In a January 2011 Rasmussen survey, respondents said that renewable energy is a better long-term investment than fossil fuels by a margin of 66 to 23 percent.

18

Environmental protection and economic growth are generally accorded a roughly equal priority, though the young prioritize the environment and older Americans prioritize economic growth. If anything, the environment tends to edge out growth as the overall top priority.