The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity (21 page)

Read The Price of Civilization: Reawakening American Virtue and Prosperity Online

Authors: Jeffrey D. Sachs

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Economic Conditions, #History, #United States, #21st Century, #Social Science, #Poverty & Homelessness

Our great sociologists and economists also remind us that it’s not only mass society that has succumbed to mass commercialization, but also the rich. Early modern capitalism was built not on the goal of luxurious consumption by the rich, but rather on the virtue of prudent consumption and high saving by the entrepreneur. The German sociologist Max Weber described the highest ethic of early capitalism to be “the earning of more and more money, combined with the strict avoidance of all spontaneous enjoyment of life,” as befitting the Protestant values of the time.

11

The British economist John Maynard Keynes made a similar observation about the moral

underpinnings of British capitalism in the late nineteenth century. The point, he wrote, was that late-nineteenth-century society tolerated the rich because they lived properly and correctly, by accumulating vast wealth but not consuming it. As Keynes put it:

Herein lay, in fact, the main justification of the capitalist system. If the rich had spent their new wealth on their own enjoyments, the world would long ago have found such a régime intolerable. But like bees they saved and accumulated, not less to the advantage of the whole community because they themselves held narrower ends in prospect.… The capitalist classes were allowed to call the best part of the cake theirs and were theoretically free to consume it, on the tacit underlying condition that they consumed very little of it in practice. The duty of “saving” became nine-tenths of virtue and the growth of the cake the object of true religion.

12

As another example, America’s greatest late-nineteenth-century capitalist, steel man Andrew Carnegie, similarly distinguished between the worthy calling of making money and the proper use of the wealth once made. In his famous and enormously influential “The Gospel of Wealth,” Carnegie defined what he called the “duty of the man of wealth”:

To set an example of modest, unostentatious living, shunning display or extravagance; to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent on him; and, after doing so, to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer, and strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which, in his judgment, is best calculated to produce the most beneficial results for the community—the man of wealth thus becoming the mere trustee and agent for his poor brethren,

bringing to their service his superior wisdom, experience, and ability to administer, doing for them better than they would or could do for themselves.

13

In this way, wrote Carnegie, the wealth of the capitalists would be deployed for the benefit of the entire community. Carnegie established several major philanthropic institutions in the United States and Europe, such as the Carnegie Endowment, the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), and numerous Carnegie libraries around the United States. He in turn inspired John D. Rockefeller to establish the Rockefeller Foundation, perhaps the most successful and influential philanthropic effort in modern history, as it contributed to fundamental advances in the fight against poverty, hunger, and disease, and to countless breakthroughs in the sciences and public administration. Carnegie’s social gospel lives on today in the philanthropic efforts of Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, George Soros, Ted Turner, Bill Gross, and other wealthy Americans who are giving away vast sums in the pursuit of poverty eradication, public education, disease control, and strengthening of democratic institutions. Gates and Buffett have also actively encouraged dozens of their fellow billionaires to commit to donating at least half of their wealth in philanthropic efforts.

What does not live on, however, is the original moral underpinning of capitalism. Today’s great wealth holders, with the notable exception of the few leading corporate philanthropists, are much better known for their profligacy than their asceticism. Birthday parties, weddings, anniversaries are celebrated with high profile, multimillion-dollar bashes that are designed for the paparazzi and public titillation in service of their self-gratification. And the public duly obliges by keeping their eyes firmly fixed on the round-the-clock cable coverage. Hypercommercialism has reached the highest levels of the society, and has helped blind the super-rich to the dire needs of the rest of society.

Advertising in the Facebook Age

The TV age is quickly becoming the broadband age, when information is carried into our lives through a dizzying array of Internet-linked devices. A great debate has begun: what will the Internet and always-on connectivity mean for our society?

When the Internet was first invented and the World Wide Web became a new vehicle for mass communication and diffusion of information, many pioneers of the new technology believed that it would be profoundly democratizing and anticommercial in its effects. Access would be free or nearly so, and everybody’s voice could contribute equally to the new global debate and discussion. The old monopolies of information would quickly be dissipated, and a new global cooperation would ensue.

Those hopes, alas, are quickly fading. The Internet has apparently fragmented, rather than unified, the public square. Many observers argue convincingly that the logic of largely self-contained groups organized on the Internet around shared beliefs is leading to further polarization and increasingly aggressive surliness in the public debate.

As for commercialization, the Internet offers advertisers and marketers the most powerful tool yet for directing their messaging to target groups. By monitoring our online behavior—the websites we visit, the purchases we make, the individuals we “friend” on social networks—advertisers have new tools to spread messages and to use social relations to track customer behavior, create fads, and foment peer pressure. Major websites such as Google and Facebook have been only too ready to turn the virtual communities they assemble over to the marketing firms. Remarkably, Google topped $25 billion in advertising revenue in 2010, and Facebook hit $1.86 billion. The not-so-hidden persuaders have been invited even more personally into our lives and vulnerabilities through the wonders of the new social networks.

14

Each day we are discovering new risks to privacy and to Web-empowered marketing, which is not surprising given the fact that some businesses will cross any line in the quest for profit. The latest development is a host of companies that create detailed dossiers on Web users, including their names, demographic information, addresses, financial information, buying patterns, social networks, political affiliations, and much more. This information is collected by way of small computer codes, “cookies” or “Web bugs,” that the firms secretly insert into personal computers when certain websites are visited or enabled, thereby allowing the firms to monitor the Internet use of the individuals and, in a Web-based network with cooperating firms, to piece together highly detailed and intrusive data sets about millions of individuals. These data sets are then sold commercially or to political campaigns and parties. According to a report in

The Wall Street Journal

, one of these companies, RapLeaf, had “indexed more than 600 million unique email addresses … and was adding more at a rate of 35 million per month.”

15

The evidence regarding the Internet and our psyches is even harsher. For a public already spinning from relentless TV, DVDs, movies on demand, MP3 players, and ever-smarter phones, the Internet seems to be rewiring not only our social networks but our neural networks as well. The latest concern of neuroscientists is that Internet browsing may undermine our long-term concentration in favor of our short-term responsiveness to stimuli. We don’t read on the Internet so much as we scan the screen. Surfing is different from reading, both emotionally and cognitively. We can retrieve facts much faster, but we retain them for less time.

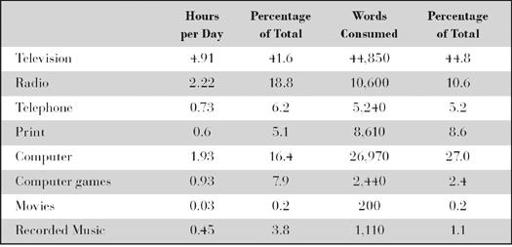

Psychologists and sociologists will no doubt increase their focus on our sensory overload in general. Studies of information transmission in our digital age show the remarkable increase in overall information flows per person but don’t yet reveal the consequences to our mental well-being and still less for our society. A remarkable study by the Global Information Industry Center documents the startling increases in information flows and the changes in composition

as well.

16

In 2009, the average American consumed “information” for around 11.4 hours per day, up from 7.4 hours per day in 1980 and no doubt still less in earlier years. These information flows come in a remarkable range of delivery systems: television (including network, satellite, cable, DVD, mobile, and other), print (books, magazines, and newspapers), radio, telephones (fixed and mobile), movies, recorded music, and computers (including games, handheld devices, Internet, e-mail, and offline programs).

The study measured the flow of information in three ways: by hours spent receiving the information, by number of words transmitted, and by number of gigabytes of information transmitted. The last puts a premium on video and computer games. The information per American for 2009, in total and as shares of the respective categories, is shown in

Table 8.2

. Notice that TV still dominates in terms of hours spent (4.91 per day) and words received (44,850 per day). TV is second in terms of gigabytes behind video games. I say “still” because of the evidence that TV use is now apparently declining among younger people in favor of other forms of information flows such as computers, mobile phones, and e-readers. Electronic screens are ubiquitous and in round-the-clock use, but now in a widening array of devices.

Table 8.2: The Daily Flow of Information, 2009

Source: Data from Global Information Industry Center (2009).

An Epidemic of Ignorance

Print media continues its long-term decline. In 1960, print delivered an estimated 26 percent of words transmitted. By 2008, that had declined to 9 percent. While TV absorbed 42 percent of the daily hours the average American spends receiving information, print media accounted for a meager 5 percent. Reading for fun is a disappearing practice among the young, and purchases of books went into a steep decline a decade ago. As Americans stop reading, ignorance of basic facts, especially scientific facts about such politically charged issues as climate change, has soared. Reading proficiency is also plummeting.

17

It would be a profound irony if the new “information age” in fact coincides with the collapse of the public’s basic knowledge regarding key issues that we confront both as individuals and as citizens. It’s far too early to tell whether the Internet and other connected devices will end up leaving society dumber or better informed. Will video games and online streaming of entertainment end up crowding out more meaningful reading and gathering of information? These risks seem real, at least according to the flood of recent books such as

The Dumbest Generation

,

Idiot America

,

The Age of American Unreason

, and

Just How Stupid Are We?

Recent polling data and academic studies do suggest that Americans lack basic shared factual knowledge. As one author recently put it, “The insulated mindset of individuals who know precious little history and civics and never read a book or visit a museum is fast becoming a common, shame-free condition.”

18

If American high school test scores continue to rank poorly relative to other countries, so, too, will our economic prosperity, sense of economic security, and place in the world. Even more ominously, our capacity as citizens will collapse if we lack the shared knowledge to take on challenges such as balancing the federal budget and responding to human-induced climate change.

The Pew Research Center occasionally surveys the basic knowledge

of the American public in its News IQ Quiz.

19

At the end of 2010, only 15 percent could identify the prime minister of the United Kingdom and only 38 percent could choose the incoming U.S. House speaker from a list of four names. Slightly under half (46 percent) knew that the Republicans would control the lower house of Congress but not the Senate. And 39 percent correctly picked out defense as the largest budget item in a list that included Social Security, interest on the debt, and Medicare. None of these gaps in knowledge is a cardinal sin. As Pew put it, “the public knows basic facts about politics, economics, but struggles with specifics.” But when the country must grapple with complex choices about taxes, spending, military outlays, and the rest, the lack of basic knowledge becomes dangerous. A poorly informed public is much more easily swayed by propaganda and much less able to resist the dark maneuvers of the special-interest groups that pull the strings in Washington.