The Price of Glory (40 page)

Read The Price of Glory Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

Two companies of the 124th carried the German trenches by assault. They penetrated there without firing a shot. But they were insufficiently supplied with hand-grenades.… The Boche counter-attacked with grenades. The two companies, defenceless, were annihilated. The 3rd Battalion, coming to their aid, was smashed up by barrage fire in the approach trenches. Altogether nearly 500 killed or wounded.… The dead were piled up as high as the parapet.…

Serving with the 124th was twenty-one-year-old Second Lieutenant Alfred Joubaire, who had marched to Verdun a few days previously behind the regimental band gaily playing

Tipperary

. For the past

fifteen months he had kept a diary which was largely restricted to matter-of-fact, almost flippant observations of life at the front. His entry for May 23rd (one of the last before a shell killed him) ends on a remarkably different note:

Humanity is mad! It must be mad to do what it is doing. What a massacre! What scenes of horror and carnage! I cannot find words to translate my impressions. Hell cannot be so terrible. Men are mad!

By late afternoon of the 23rd Lefebvre-Dibon’s battalion to the right of the fort was encircled and forced to fly the white flag; over seventy-two per cent of its effectives were either dead or wounded. On top of the fort, the 129th was now also cut off. Still its machine-gun post at the southwest turret hammered away stubbornly. But ammunition was running out. Worse still, because the French had never occupied the whole superstructure, the Germans were able to push reinforcements into the fort underground, through a tunnel at the northeast corner. By this means, they smuggled up a heavy mine-thrower on the night of the 23rd. As the sun rose through the Meuse haze, the weapon had been built into an emplacement less than eighty yards from the French machine-gunners, but impervious to their direct fire. In rapid succession it lobbed eight aerial torpedoes, each containing a huge charge of explosive, at the south west turret. Before the smoke from the last shattering blast cleared away, three German companies leapt out of the fort on to the stunned survivors.

It was the end. That night a few remnants of the French spearhead crept back to their lines in ones and twos. Heavy as the defenders’ losses had been those of the French were incomparably higher, with a thousand prisoners alone left in enemy hands. Mangin’s 5th Division had not as much as a single company in reserve, and for a time there was a dangerous hole in the front 500 yards wide. Mangin himself was abruptly withdrawn from the sector by his Corps Commander, Lebrun, passing — for neither the first nor last time — into temporary disgrace. The whole episode was a tragic case of too little, too soon. Had the forces been available to attack on a broader front — as Pétain had wanted — the fort might possibly have been retaken. But since they were not, the attack should clearly not have taken place when it did. Pétain assumed full responsibility for the debacle,

and the fact that his account of the battle contains no single breath of reproach for Nivelle or Mangin reveals a magnanimity rare among the

ex post facto

writings of war leaders.

But, at the front, the failure brought about a noticeable decline in morale. Ominously, cases of ‘indiscipline’ were reported from Verdun towards the end of May. In Paris, the news of Douaumont threw Galliéni of the Marne, already weakened by an operation, into a profound depression. Two days later he was dead.

CHAPTER TWENTY

‘MAY CUP’

Of all man’s miseries the bitterest is this: to know so much and to have control over nothing.—HERODOTUS.

… I cannot too often repeat, the battle was no longer an episode that spent itself in blood and fire; it was a conditioned thing that dug itself in remorselessly week after week….— ERNSI JUNGER,

The Storm of Steel

As May gave way to a torrid June at Verdun, the three-and-a-half-month-old battle entered its deadliest phase. It was not merely the purely military aspects that made it so. In all man’s affairs no situation is more lethal than when an issue assumes the status of a symbol. Here all reason, all sense of value, abdicate. Verdun had by now become a transcendent symbol for both sides; worst of all, it had by now become a symbol of honour.

L’honneur de France!

That magical phrase, still capable today of rousing medieval passions, bound France inextricably to the holding of Verdun’s Citadel. To the Germans, its seizure had become an equally inseparable part of national destiny. On a plane far above the mere warlords conducting operations, both nations had long been too far gone to be affected by the strategic insignificance of that Citadel. In their determination to possess this symbol, this challenge-cup of national supremacy, the two nations flailed at each other with all the stored-up rage of a thousand years of Teuton-Gaul rivalry. Paul Valéry, in his eulogy welcoming Marshal Pétain to the Academie, referred to the Battle of Verdun as a form ‘of single combat… where you were the champion of France face to face with the Crown Prince’. As in the single combats of legend, it was more than simply the honour, it was the virility of two peoples that was at stake. Like two stags battling to the death, antlers locked, neither would nor could give until the virility of one or the other finally triumphed.

Confined to the most sublime plane, Valéry’s metaphor was a noble and apt one. But, to the men actually engaged in it, a less noble form of symbolism was apparent. In the last days of peace, there had seemed to come a point where the collective will of Europe’s leaders had abdicated and was usurped by some evil, superhuman

Will from Stygian regions that wrested control out of their feeble hands. Seized by this terrible force, nations were swept along at ever-mounting speed towards the abyss. And once the fighting had started, one also senses repeatedly the presence of that Evil Being, marshalling events to its own pattern; whereas in the Second World War somehow the situation never seemed entirely to escape human manipulation — perhaps because the warlords, Churchill and Roosevelt, Hitler and Stalin, were titans when contrasted with the diminutive statures of the Asquiths, the Briands, and the Bethmann-Hollwegs. So now, as the Battle of Verdun moved into June, its conduct had in fact been placed beyond the direct control of the two ‘champions’, Pétain and Crown Prince Wilhelm. With the ascendancy of Nivelle and Knobelsdorf, each pledged to the continuance of the battle regardless of cost, the fighting had reached a higher peak of brutality and desperation. The battle seemed to have somehow rid itself of all human direction and now continued through its own impetus. There could be no end to it, thought one German writer,

until the last German and the last French hobbled out of the trenches on crutches to exterminate each other with pocket knives or teeth and finger nails.

In the diaries and journals of the time, on both sides, mention of the vileness of the enemy becomes more and more infrequent; even the infantryman’s hatred for the murderous artillery grows less pronounced. The battle itself had become the abhorred enemy. It had assumed its own existence, its own personality; and its purpose nothing less than the impartial ruin of the human race. In the summer of 1916, its chroniclers accord it with increasing regularity the personifications of ‘ogre’, ‘monster’, ‘Moloch’ and ‘Minotaur’, indicative of the creature’s insatiable need for its daily ration of lives, regardless of nationality. All other emotions, such as simple, nationalist, warlike feelings, had become dwarfed in the united loathing of the incubus; at the same time it was accompanied by a sense of hopeless resignation that would leave an indelible mark on a generation of French and Germans.

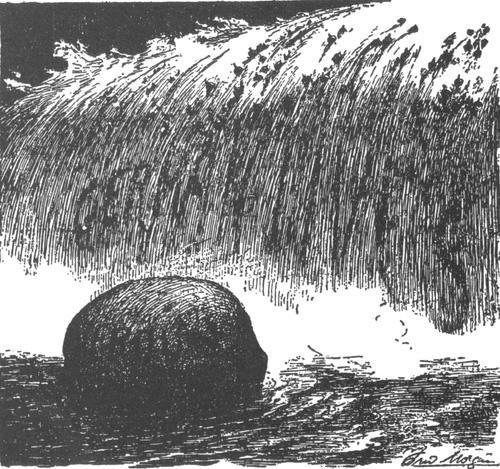

Abroad, beyond the general admiration for France’s heroism at Verdun, there was widespread unanimity in the kind of symbol it evoked among the cartoonists. In the United States,

The Baltimore

American

printed an adaptation from Millet, with the Kaiser sowing skulls at Verdun; and a similar figurative device was employed by the

Philadelphia Inquirer,

above a caption of ‘Attrition Gone Mad’.

1

In an Italian cartoon Death says to the Crown Prince, ‘I am weary of work — don’t send me any more victims’; a British cartoon of the period shows Death sitting on top of the world — ‘The only ruler whose new conquests are undisputed.’ From Germany, a grisly armed knight pours blood over the earth out of a copious ‘Horn of Plenty’, and in a propaganda medallion — dedicated with an ironic twist of things, to Pétain — Death is portrayed as a skeleton pumping blood out of the world. Looking back from the autumn of 1916, the

New York Times

summarised the diseased,

Totentanz

imagery which Verdun had sparked off with a monstrous Mars surveying three-and-a-half million crosses; ‘The end of a perfect year’.

The Sower

—

From The Baltimore American

.

As ye sow, so shall ye reap.

* * *

When the Chief-of-Staff of the German Third Army visited Supreme Headquarters during the French counter-attack on Douaumont, he had found the normally insusceptible Falkenhayn rubbing his hands with glee, declaring that this was ‘the stupidest thing they could do’. Far from disrupting new German offensive plans

as Nivelle might have hoped, the French failure temporarily halted Falkenhayn’s wavering and threw his full support behind Knobelsdorf. Preparations for the new assault, bearing the delectable code name of ‘MAY CUP’, now went ahead at top speed, with reinforcements in men and material promised by Falkenhayn. The prospects seemed rosier than they had for some time; the French line on the Right Bank had been seriously weakened by the losses suffered in the Douaumont venture;

1

there were also indications of a decline in morale. On the Left Bank, both the commanding hills of Mort Homme and Côte 304 had been taken at last, and from them German guns could place a deadly restraint on the French heavy artillery massed behind Bois Bourrus ridge. Despite all Pétain’s efforts, by the end of May the Germans still had an appreciable superiority in artillery at Verdun, with 2,200 pieces against 1,777. Everywhere the French margin of retreat had become exceedingly slim. Once again the German Press was encouraged to declare bombastically:

Wearing-Down Tactics

— © 1916,

by The Philadelphia Inquirer

.

“Attrition” Gone Mad.

‘Assuredly we are proposing to take Verdun.…’

‘MAY CUP’, the most massive assault on the Right Bank since the initial onslaught in February, was to be launched with three army corps, I Bavarian, X Reserve, and XV Corps, attacking with a total of five divisions. The weight of the attack was nearly equal to that of February 21st, but this time it was concentrated along a front only five, instead of twelve kilometres, wide; or roughly one man for every metre of front. This time there would be no surprise, no provision for manoeuvre; the attack would punch a hole through the French lines by sheer brute force alone. Its objective was to gain ‘bases of departure’ for the final thrust on Verdun. These comprised, reading from west to east, the Thiaumont stronghold, the Fleury ridge and Fort Souville; but, first and foremost, Fort Vaux, the bastion on which was anchored the northeastern extremity of the French line.

It will be recalled that premature claims to the capture of Fort Vaux had brought much ridicule upon the Germans in early March. There had been subsequent vain attempts to take the fort in April and May; with Falkenhayn arriving in person to attend its delivery on the last occasion. After each failure, the German

infantry had been pulled back while the 420 mm. ‘Big Berthas’ resumed the siege.