The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (53 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

Prime Minister Begin welcomes President Sadat, with President Ephraim Katzir

Photograph credit: Moshe Milner & Israel Government Press Office

Pres. Sadat, P.M. Begin & Pres. Katzir stand at attention during the playing of the Egyptian and Israeli national anthems

Photograph credit: Ya’acov Sa’ar & Israel Government Press Office

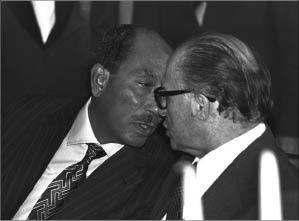

President Sadat and Prime Minister Begin in discussion in the course of a working dinner at the King David Hotel, Jerusalem, 19 November 1977

“But now I am here,” he said.

“Shalom. Welcome,” she said.

He continued along the carpet, shaking the hands of the rest of the ministers and of the other notables, until, at a given signal, a young captain of the guard, head high, chest out, marched forward, and with a whirling salute informed the Egyptian president that the

IDF

guard of honor was ready for his inspection. Walking with measured steps, President Sadat inspected the ranks, semi-bowed to the blue-and-white flag, and then, standing side by side with President Katzir and Prime Minister Begin, heard the band play his national anthem, followed by

“

Hatikva

,” their contrasting harmonies punctuated by the thumps of a twenty-one-gun salute.

An armored limousine pulled up alongside the Egyptian president, but a pack of pugnacious newsmen mobbed the vehicle, overwhelming President Katzir, who was Sadat’s intended traveling companion for the ride to Jerusalem. He, being an elderly, genteel man, slow of gait, was pushed aside and would have been left behind were it not for the quick-wittedness of a security agent trotting alongside the car who saw him safely inside.

Thus did the presidential motorcade set off for the drive up to Jerusalem, where houses were bedecked with Israeli and Egyptian flags, and cheering crowds filled the streets. Here was history in the making. Strangers embraced in unbounded optimism, and the sound of wave upon wave of hurrahs swept through the windows of the King David Hotel, where the president of Egypt was lodging. Common folk stood vigil all through the night outside, as if silently entreating the man inside to be the bearer of good tidings that the wars were ended for good.

Most of the thirty-six hours of the Egyptian president’s stay were taken up with ceremonial and public events: a prayer service at the al-Aksa Mosque on the Temple Mount, a visit to the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial, meetings with representatives of the parliamentary parties, a working lunch with the prime minister and his senior colleagues, a festive dinner, and a joint press conference. At the center of it all, was his address to the Knesset.

That day, the crowded parliament chamber had an air of high, almost tear-jerking expectancy. All rose and applauded at length at the entrance of the president of Egypt accompanied by the president of Israel.

“I have come to the Knesset,” the visitor began, “so that together we can build a new life, founded on peace.”

The clapping rattled the rafters, and it continued during Sadat’s lengthy ode-to-peace, given in a stilted English. It was only when he moved on to list the conditions with which Israel would have to agree if it ever wanted Arab acceptance, conditions untenable to the overwhelming majority, that the chamber stilled to an intensely grave attentiveness. No, the president of Egypt told his audience, he would not sign a separate peace agreement. No, he would not enter into any interim arrangements. No, he would not bargain over a single inch of Arab territory. No, he would not compromise over Jerusalem. And no, there could be no peace without a Palestinian state.

Begin’s response was cordial but emphatic: His guest had known before embarking on his journey to Jerusalem exactly where Israel stood on each of these issues. He urged negotiations without prior conditions. With goodwill, he added, a redeeming formula could be found to resolve all the admittedly complex matters.

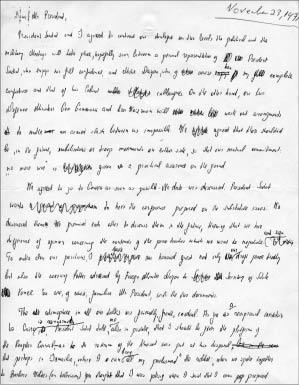

Perhaps in the course of their private conversations the two leaders had found ways to bridge this seemingly impassable chasm. Perhaps Sadat’s declared conditions for peace were not so set in stone, because after his plane had left en route to Cairo, an exuberant Begin beckoned me over, across the tarmac, and said, “I want to send off a cable to President Carter straight away,” and on the spot he began to dictate while walking to his car. As anyone who has tried it well knows, writing while walking is no easy feat, and my resultant scribble was so illegible I had tremendous difficulty deciphering it. Once I did, it came out like this:

Dear Mr. President

–

Last night President Sadat and I sat till after midnight. We are going to avert another war in the Middle East, and we made practical arrangements to achieve that quest. I will give you the details in a written report. The exchanges were very confidential, very far-reaching from his point of view. I am very tired. I work twenty hours a day. There are differences of opinion. We are going to discuss them. I have a request. You will plan another trip to various parts of the world. Please visit both Egypt and Israel during that trip. Sadat was very moved by the reception of our people. You will come to Israel and we will give you a wonderful time. So will Egypt. Give two days to Jerusalem and Cairo. Please take this into consideration.

That same night, the prime minister, exhausted though he was, received a four-man delegation of United Jewish Appeal philanthropists who had flown in from the U.S. especially to witness the historic event. Among them was an old acquaintance of mine from Columbus, Ohio – Gordon Zacks, commonly known as Gordie.

Gordie was a vigorous, enterprising, bighearted and idealistic man who not only gave generously but also thought innovatively. In 1975, while then U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was shuttling back and forth between Cairo and Jerusalem in the arduous attempt to hammer out an interim Sinai agreement between Sadat and the then prime minister Rabin, he had embarked on a peacemaking mission of his own. He had flown to Egypt to identify a hundred projects in the fields of medicine, agriculture, irrigation, industry, and social welfare which he envisioned as possible joint Egyptian-Israeli enterprises. He saw these servinge as stepping-stones to peace, and carrying his proposal to Israel he asked me to arrange a meeting with Rabin.

Draft of the official written report sent to President Carter, reporting on President Sadat's visit to Jerusalem, 23 November 1977

As Rabin had flicked through the bulky project folder, Gordie leaned across and said to him with enormous zest, “Yitzhak, listen to me, this is a no-lose deal.”

“Meaning what, exactly?” asked Rabin, slamming the folder shut without even pretending to examine a single one of its projects.

“Meaning, here is a way of testing Sadat’s true intentions toward peace.”

“Gordie, what world are you living in?” scoffed Rabin sarcastically, pushing the folder away as if its author was one of the proverbial babes in the wood.

“I’m telling you, this is a solid proposal,” countered Gordie indignantly. “Israel could offer to become a part of any or of all these projects. It could lay the foundations for the beginnings of a true dialogue.”

“And if the Egyptians say we don’t want you, as I’m sure they will?”

“Then what you do is publicly offer them two projects a week for fifty weeks. You will come out smelling of roses as the peacemaker, while Sadat will be seen as the intransigent one.”

“Crazy, naive American,” said Rabin, rising and extending a hand of farewell. “Gordie, old friend, this is just another public relations gimmick. Go back home to America and do what you do best: raise money for the United Jewish Appeal.”

And off Gordie went, dejected.

Two years later, when Menachem Begin assumed the premiership, he asked to see all materials concerning Israel’s past peacemaking efforts with Egypt. Among the documents was Gordon Zacks’ proposal. It aroused enough curiosity for the premier to ask me who the man was, and when I told him of his

UJA

leadership role and his political activism on Israel’s behalf, he said, “His ideas are a fantasy, but they show daring and imagination. I’d like to meet him one day.”

I phoned this through to Gordie and within a week he was having lunch with the prime minister in the Olive Room at the King David Hotel.

“Mr. Zacks, have you ever been in jail?” asked Begin, while the first course was being served.

“No, Mr. Prime Minister,” answered Gordie testily, wondering what Begin was getting at, “I’ve never been in jail.”

“That’s a pity,” said Begin enigmatically, nibbling on his chicken. “You see, I have been in three different jails.”

Gordie Zacks sat back, stunned. “Three? How come?”

“The first time the communists arrested me was in Vilna. I was in the middle of a game of chess. When the Soviet agents dragged me off, I remember calling out to my colleague, ‘I concede the game. You win.’ The Soviets locked me up in one of their prisons. I was held there for six weeks, and all I could think about was getting out and going back home. The second prison was a forced labor camp

–

a gulag

–

in Siberia. By the sixth week, I dreamt of being back in that first prison cell. The third time, the Soviets put me in solitary confinement, and I dreamt of being back in that Siberian labor camp. So, you see, Mr. Zacks, my job as prime minister of Israel is to make sure that Jewish children dream the dreams of a free people, and never about prisons, or labor camps, or solitary confinement. I want to bring them peace, but in our region peace can be won only through strength.”

“So, how can I help?” asked Gordie, with his characteristic wholeheartedness.

“By telling me about your trip to Egypt, and the nature of the projects we might do together with the Egyptians once we have peace.”

It was no wonder, with that history, that Gordie Zacks displayed such excitement that night at the conclusion of Sadat’s visit, when Begin told him and his colleagues, “Friends, you will be pleased to hear that President Sadat and I have come to an understanding. We still have our differences, as you heard in his Knesset speech and in my response to him, but we agreed there will be no more war. I already wrote as much to President Carter. Yehuda”

–

this to me

–

“you sent off my cable?”

“Of course, as soon as I got back to Jerusalem from Ben-Gurion.”

“Then let’s call the president now

–

hear his reaction.”

“Do you have his number?” I asked.

Begin shook his head with an air of innocent ignorance.

“Then I’d better rush over to the office. I have it in the classified telephone directory,” I said.