The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (54 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

“Why not call the international exchange, and ask for the White House switchboard,” suggested Gordie helpfully. “I’m pretty sure they have a general number.”

“I’ll try,” I said, and soon enough I got through to 001 202 456 1414. I was standing in the hallway, speaking to a woman at the White House switchboard, who thought I was a crank.

“I’m sorry, mister,” she said in a steely voice, “but you can’t speak to the president of the United States.”

“It’s not me, it’s the prime minister of Israel, Mr. Menachem Begin,” I said haughtily.

To which she responded dubiously, “Menakem who?”

“Begin.”

“Hold the line.”

“Hello, how can I help you?” This from a lady with a more gentle tone.

I explained the matter, and she said reasonably, “Please give me the prime minister’s number and we’ll get back to you.”

I checked the phone to see the number. There was none. How could there be? This was the prime minister’s residence, and his number was not on public display for prying eyes to see. So I called out to the prime minister, who was sitting in the lounge with his guests, “Mr. Begin, what’s your number?”

“I’ve no idea. I never phone myself,” he said. And then, moving into the hallway he shouted up the stairwell to his wife, “Alla, what’s our phone number?”

“Six six four, seven six three,” she shouted back.

I scribbled it down and repeated it to Washington.

“Thank you,” said the voice, “we’ll get back to you presently.” And, sure enough, within minutes, the phone rang and the voice said, “Please put the prime minister on the line. I’m putting the president through now.”

I handed over the receiver and stood aside to take notes. With no extension to hand, I could only record one side of the conversation, what Mr. Begin was saying.

“I hope you received my message, Mr. President,” he said beamingly.

Long pause.

“Oh yes, of course. Tomorrow I shall send you a full account, through our ambassador,” he said.

Another long pause.

“Certainly, indeed, Mr. President. Yes, there are immediate concrete results. President Sadat and I agreed to continue our dialogue on two levels, the political and the military. Such meetings will take place hopefully between our representatives soon. We made a solemn pledge at our joint press conference in Jerusalem that there will be no more wars between us. This is a great moral victory. And we agreed that there be no future mobilizations or troop movements on either side, so that our mutual commitment of ‘no more war’ may be given a practical expression on the ground.”

And then, shoulders back, head rising, forehead wrinkling, “No, no, Mr. President, I assure you

–

yes, yes

–

we still want to go to Geneva if you think it useful. It is all a matter of proper timing. President Sadat and I discussed this, but did not talk about an actual date. We exchanged ideas on the most substantial issues, and knowing we have differences of opinion we promised each other to discuss them further in the future. What is important is that the atmosphere throughout all our talks was friendly, frank and cordial.”

Then, face all a-grin, voice bubbling, “Mr. President, without you it could never have happened. So allow me to express my deepest gratitude for your magnificent contribution. Peace-loving people the world over, and the Jewish people for generations to come, will be forever in your debt for the role you played in helping to bring this historic visit about. We shall need your understanding and help in the future. God bless you, Mr. President. Goodbye,” and he hung up.

Privy to every word, his guests in the lounge fervently congratulated him on what was, assuredly, an affable conversation

–

all of them that is, but Gordie Zacks. Dumbfounded, he asked, “Why Mr. Prime Minister?

Why?

Why give Carter so much credit? Sadat came here because of what you did, and

despite

what Carter did, with his idea of Geneva with the Soviets.”

“What does it cost?” answered Begin with an impish expression. “I’m still going to need him, aren’t I? So giving him a bit of credit now might help us a little in the future. The important thing is that Sadat and I are agreed on making peace with or without Geneva.”

A week later, on 28 November, in an address to the Knesset, the prime minister summarized the historic visit, and the initiatives which had brought it about. He reiterated his gratitude to the United States, and explained why eight o’clock had been deliberately chosen as the hour for the Egyptian President’s arrival at Ben-Gurion Airport. He said:

President Sadat indicated he wished to come to us on Saturday evening. I decided that an appropriate hour would be eight o’clock, well after the termination of the Shabbat. I decided on this hour in order that there would be no Shabbat desecration. Also, I wanted the whole world to know that ours is a Jewish State which honors the Sabbath day. I read again those eternal biblical verses: “Honor the Sabbath day to keep it holy,” and was again deeply moved by their meaning. These words echo one of the most sanctified ideas in the history of mankind, and they remind us that once upon a time we were all slaves in Egypt. Mr. Speaker: We respect the Muslim day of rest – Friday. We respect the Christian day of rest – Sunday. We ask all nations to respect our day of rest – Shabbat. They will do so only if we respect it ourselves.71

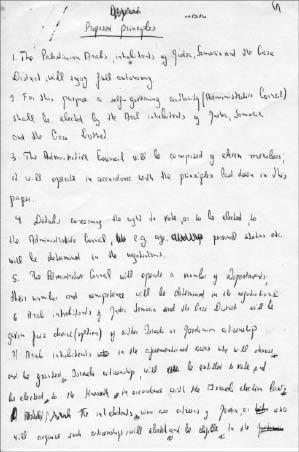

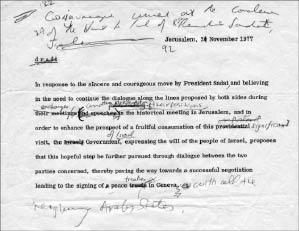

Author's corrections on initial draft of joint Egypt-Israel communiqué issued at the end of President Sadat's visit to Jerusalem, 20 November 1977

Photograph credit: Israel Government Press Office

The author with President Sadat, Ismailia, Egypt, 25 December 1977

Deadlock

Within a matter of weeks, all the protocols for the Egyptian-Israeli talks were in place, and meetings between the two sides began. An air of expectancy gripped the nation, as if some miracle was in the offing; the creation of a redemptive, instant peace treaty. But it was not to be. Like Sisyphus, whenever Menachem Begin pushed his boulder up the steep hill of negotiation, it always came rolling down again over his toes, with painful and prolonged consequences.

Anwar Sadat assumed that his grand reconciliatory gesture of coming to Jerusalem would be rewarded by a grand reconciliatory gesture on the part of Menachem Begin, in the form of a withdrawal on all fronts back to the pre–Six-Day War 1967 lines, and acquiescence in the establishment of a Palestinian state. Small wonder, then, that whenever the Egyptian and Israeli representatives met, they faced an unbridgeable abyss of misunderstanding and deadlock. Their joint committees broke up in angry dispute, indignant letters were exchanged, the Carter administration told American Jewish leaders that the Begin government was being unnecessarily obdurate, and the heavily censored Egyptian press treated Israel with disdain and its prime minister with malice. Begin was depicted as a Shylock.

This affront upset him deeply. His hurt was reflected in the withering sarcasm of the occasional working notes he would send me, addressing them, “From Shylock to Shakespeare,” and signing them, “Menachem Mendel Shylock.”

By the spring of 1978, the talks were in the doldrums and Jimmy Carter had to intervene urgently in an effort to rescue the waning hopes. He pressed Begin to come to Washington to thrash things out. The prime minister, knowing what lay in store, asked Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan to accompany him.

The acrimony of those talks, held in the White House Cabinet Room on 21 and 22 March, is vividly illustrated in the following exchange, which I recorded verbatim. What follows is the full version:

Begin:

…We decided, in our July talks last year, to talk frankly. When I saw you [privately] at that time I read to you a three-point document. You sent me a five-point response and, in it, you used language that said we would have to withdraw ‘on all fronts.’ I said we would not agree to such language. I later said we had a claim and a right to sovereignty in Judea, Samaria, and Gaza, but that we would leave that claim open. So we did two things in an effort to make an agreement [with Egypt] possible: First, we did not apply Israeli law to Judea, Samaria, and Gaza, proposing that the question of their future sovereignty be left open. Secondly, we offered administrative self-rule for the Palestinian Arabs in these areas, and suggested that their autonomy would be reviewed after five years. After five years all questions would be open for renegotiation. These, I submit, Mr. President, are far-reaching proposals.

Carter:

They nevertheless represent a change compared to the position of previous [Labor] governments [i.e., a readiness for a withdrawal on all fronts, including the West Bank].

Begin:

Yes, but not a drastic change. Under previous governments, the Jordan River was to be designated as Israel’s security boundary. There was to be no Israeli withdrawal from the river. The Labor governments planned to evacuate only a part of the West Bank. The Israeli Army was to remain along the Jordan River.

Carter:

In an effort to break the present deadlock, could you envisage that your security needs could be met by having Israeli military forces deployed for a period of five years in military positions along the river, or in the hills around Jerusalem? In other words, would you agree to withdraw into

cantonments

in a manner that would satisfy Arab demands and yet preserve your security? Is that a possibility?

Begin:

I don’t know about the word cantonments. We could consider withdrawal into emplacements. In all circumstances, our forces must stay in Judea, Samaria, and Gaza.

Dayan:

I would like to refer to the question of whether there has been a change in the policy of the present government compared to the [Labor] governments of the past. I was in previous Labor governments, and I can tell you that for several months after the Six-Day War, the Israeli position was that we would return the whole of Sinai and the Golan Heights in return for assurances, but we totally excluded the West Bank…the plan of the present government to offer the Palestinian Arabs a regime of self-rule grants them a far greater measure of genuine self-expression than any plan of previous Israeli governments. Our current plan begins with the proposition that we don’t want our forces to rule over the Arabs. We don’t want to impose ourselves on them. We don’t want to tell them how to run their lives. But we must be in a position to check the movement of those who cross into our territory. Among the Palestinians are refugees, laborers, and, yes, terrorists. Speaking as an ex-soldier, I want to know who will be in charge of the border checkpoints from Jordan and Syria into the Palestinian and Israeli areas. If our own soldiers are not going to do the checking we shall have to fence off our whole country with barbed wire. I don’t want Israel to become an isolated fortress. We will, therefore, have to deploy our soldiers in the West Bank and Gaza wherever they are needed for our security, without imposing ourselves on the daily lives of the Arabs who will, under this government’s plan, enjoy self-rule.

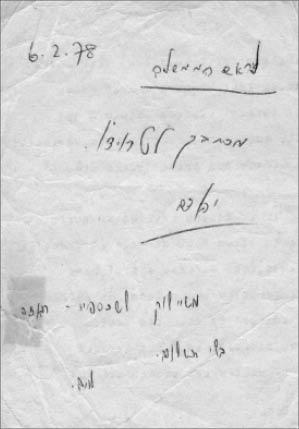

Note attached to letter from author to P.M. Begin, with P.M. Begin's reply.

Translation: “Your letter to

[

Canadian premier

]

Trudeau.”

Begin’s reply: “From Shylock to Shakespeare

–

With thanks. No payment,” 6 February 1978

Carter:

Let me repeat one thing. I have no doubt that Sadat really wants a peace agreement with Israel. I have had hours of private talks with him, and he is flexible on the issues. He has obligations to the other Arabs, and he acts as

spokesmen

for their interests. He is the best Arab leader with whom you can negotiate. But because of the pressure of the terrorists, and the pressures on Sadat himself, I am afraid that the chance for an agreement will slip away and the prospects for peace be lost.

[…]

Brzezinski:

As we try to advance toward a solution, it is important to note that your self-rule proposal can be seen in different ways. To put it bluntly, it can be seen as a continuation of your military and political control over the West Bank and Gaza. This would make it clearly unacceptable. It would render Security Council Resolution 242 ambiguous, displaying unwillingness on your part to apply the term ‘withdrawal’ to the West Bank and Gaza. If Israel were to speak of its forces being withdrawn from control of the West Bank and Gaza to agreed emplacements, then your plan could be the basis for a solution, and open the way to peace. But if not, there could be strong suspicions that you intend to perpetuate your control over these occupied territories. Need I say that the Middle East is an essential area of interest to us? It is vital that the region be engaged with the West, and be set on a course of moderation and stability. This is in your interest as well as ours.

Begin:

We all understand the need for an agreement with the Arabs. We have, therefore, elaborated a peace plan which will enable the Palestinian Arabs to elect their own Administrative Council

–

self-rule

–

and run their daily lives themselves without our interference. We only reserve for ourselves the maintenance of security and public order.

Carter:

You envisage the autonomy agreement for the West Bank and Gaza to last for five years, am I not right?

Begin:

Correct.

Carter:

What will happen after that?

Begin:

After that, we shall see. We have carefully considered the possibility of conducting a plebiscite in which the Palestinian Arabs would be given the choice of continuing the status quo, or opting for a tie with Jordan, or for a tie with Israel. However, with the pistols of the

PLO

pointing at their heads, and with the almost daily assassinations and the threats which the population constantly endures, a plebiscite will be futile and dangerous. The

PLO

will either force the people to

boycott

it or force them to vote for a Palestinian state. This we will not allow. Therefore, we suggest, let’s wait and see how the [five-year] self-rule experiment works out

–

how the reality will unfold.

Carter:

This practically gives Israel a veto

–

a de facto veto

–

even over Arab administrative affairs. And it keeps Israel in indefinite control of the West Bank. Without Israeli willingness to give the Palestinian Arabs a voice in determining their own future, there is no chance for a peace settlement. I know that Sadat won’t agree to the perpetuation of Israeli control over the West Bank, if the Palestinians are not given a guaranteed chance to choose their future. If Israel insists they have no voice, there will be no prospect of a peace settlement. You are getting more and more demanding. You are slamming the door shut.

Brzezinski:

We have to have an agreement that is satisfactory to you on security grounds, but which is politically realistic. If you want genuine security while giving the Palestinians genuine self-rule and an identity, that can work. Security

–

yes, political control

–

no.

Begin:

In our self-rule plan, we give the Palestinian Arabs the option of [Israeli] citizenship after five years. They can even choose to vote for our Knesset.

Brzezinski:

But it works both ways: Israelis are allowed to buy land in the West Bank, but there is no reciprocity for the Arabs in Israel proper. This is an unequal status.

Begin:

This is a right of our citizens.

Brzezinski:

But Israelis are not citizens of the West Bank.

Begin:

But we are giving them the option of becoming our citizens.

Dayan:

According to our plan, Palestinian Arabs after five years can opt for either Jordanian or Israeli citizenship, or they can retain the status quo, and keep their present local identity cards. We will make no obstacles to their choice. The main point about any referendum in the future is to allow individuals to decide their citizenship, but not to decide the sovereign status of Judea, Samaria, and Gaza. The kind of plebiscite you are suggesting will determine territorial sovereignty, not just the status of the people. If we allow what you call ‘deciding their own future’ in terms of territory, they will be deciding not only their own future, but ours, too. If they have a right to decide whether Israel gets out of the territories, they are, ipso facto, deciding our future.

Begin:

Nothing is excluded. There will be a review after five years. But we are not ready to commit now to a referendum that will inevitably lead to a Palestinian state under the existing conditions of

PLO

intimidation and threat. Hence, we suggest that matters be left open for review. To agree now to a plebiscite could have incalculable consequences for our future.