The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (61 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

With that, he half-bowed to the troops, as if in homage, and they applauded him with great admiration.

Israel Bonds dinner, Jerusalem Hilton, June 1980

O Jerusalem

A month or so later, Menachem Begin could be found at the Hilton Hotel in Jerusalem, standing on a flag-bedecked platform adorned with a banner as big as a billboard, that read: “BONDS FOR ISRAEL

–

THE JERUSALEM SOLIDARITY MISSION

–

JUNE 1980.” Cheers welled up from the crowded banqueting hall, where approximately two hundred American property moguls and entrepreneurs were boisterously demonstrating their fellowship with Jerusalem. They were listening to the Israeli prime minister with fierce approval, as he savaged the

UN

’s recent resolution condemning Israel. A Knesset initiative had proposed legislation to enshrine Jerusalem as Israel’s eternally united capital; the

UN

had issued a sharply-worded resolution condemning the initiative. The audience adored the prime minister’s audacious declaration that, in response, he intended to transfer his own office from West Jerusalem to East Jerusalem

–

which the

UN

insisted was conquered territory, and not legally part of Israel.

Ablaze with defiance, he shook a finger in righteous ire at the battery of television cameramen who were recording his every word and gesture, and he thundered: “CHUTZPAH! INSOLENCE! By what right does the United Nations dare tell us where the capital of Israel should be? Who arrogated to them the right to tell us where the office of the prime minister of Israel should be? Did the founders of the proud American nation ever ask anybody’s permission before they designated Washington as their capital? Did they?”

The speaker stared down at his approving visitors with glowing eyes and they responded with smiles and loud applause. When this died down, Begin’s face creased into a roguish smile, and he snickered, “By the by, may I ask you a question? If Jerusalem is

not

the capital of Israel, where

is

our capital? Petach Tikva, perhaps?”

Laughs ricocheted around the hall.

“Just as the builders of Washington endowed their capital city with the letters DC, so did the builders of Jerusalem endow our capital with the letters DC

–

David’s City.”

More guffaws and claps.

“And what exactly is our crime, ladies and gentlemen? What wrong have we done that so irritates the United Nations?”

He stepped out in front of the podium, and in a stage whisper, said, “I’ll tell you, confidentially, what our crime is. Our sovereign Knesset has the temerity to unilaterally declare Jerusalem our capital city.

Oy vey!

UNILATERALLY! Without the

UN

’s permission! What a felony!”

Then, springing back to the podium, he threw up his arms, fists balled, and in a voice that was vibrant and trembling, he cried, “We Jews did not choose Jerusalem unilaterally as our capital city

.

HISTORY chose Jerusalem unilaterally as our capital city. KING DAVID chose Jerusalem unilaterally as our capital city. That is why reunited and indivisible Jerusalem shall remain the eternal capital of the Jewish people forever.”

As the applause exploded, Begin’s voice soared higher, above it, and he repeated “YES, FOREVER AND EVER!” And then he shared how, at the very end of his Camp David talks with Jimmy Carter and Anwar Sadat, in 1978, literally minutes before the signing ceremony was due to begin, the American president approached him with “Just one final formal item.” Sadat, Carter said, was asking Begin to put his signature to a simple letter that committed him to placing Jerusalem on the negotiating table of the final peace accord.

“I refused to accept the letter, let alone sign it,” rumbled Begin. “I said to the president of the United States of America, ‘If I forgot thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget its cunning, and may my tongue cleave to my mouth.’”

This ancient admonition was borne aloft as the premier concluded amid more cheers: “My fellow Jews: Jerusalem is an epic. It is the wellspring of a civilization. Without Jerusalem’s civilization, the spiritual history of the world would be stagnant. Has anyone ever heard of a daughter or a son of a Saladin fasting each year in memory of ancient Jerusalem’s anguish? Not a one! Has anybody ever heard of a son of a Crusader who breaks a glass at his wedding ceremony in memory of ancient Jerusalem’s torment? Not a one! Throughout all its three-thousand-year-long history Jerusalem has been capital to no one but the Jews. So it was. So it is. And so it shall forever be.”

The entire audience leapt to their feet in a standing ovation, led by the chairman of the evening, Sam Rothberg, a sharp-chinned, plain-talking philanthropist, hewed from much the same flinty rock as the prime minister himself. A native of Peoria, Illinois, Sam Rothberg was an initiator of, and voluntarily led, the State of Israel Bonds campaign for years, often against the wishes of other prominent Jewish community leaders, who preferred tried and tested Israeli charities like the United Jewish Appeal. Menachem Begin respected Sam Rothberg enormously, at times treating him as a sort of ex-officio cabinet minister, charging him with helping top up the country’s development budget while also raising funds for the expanding needs of the country’s prestigious Hebrew University, whose governing board he chaired.

When the prime minister sat down, Rothberg shook his hand enthusiastically and bellowed above the hullabaloo, “Menachem, that was magnificent! Where on earth do you find the energy to cope with the two most grueling jobs in government

–

the premiership and the defense ministry, and yet still be as fresh as a daisy at this hour of the night?”

“I try to do what Napoleon did,” responded Begin, smiling, rising again to bow and wave at the still-applauding crowd. “Napoleon said of himself that he compartmentalized an array of subjects in his head, and when he wished to focus on one he simply locked the doors on all the others. Tonight, I locked everything away but Jerusalem, and on that subject, the good Lord gives me great strength. Remember the ancient words of the Almighty, ‘Hanoten l’ayef koach’” [He who gives strength to the weary].

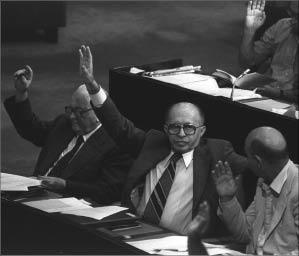

Photograph credit: Chanania Herman & Israel Government Press Office

Prime Minister Begin votes for the Jerusalem Bill, 29 July 1980

“So how much sleep do you manage on?” asked Rothberg, amid the din.

“Though I only managed a couple of hours last night,

Hanoten l’ayef koach

saw me through the day. So now I shall go home, have a quiet nocturnal chat with my wife, study the latest dispatches, get a few hours rest, and,

im yirtze Hashem

[God willing], be ready to start tomorrow afresh.”

The next day, the prime minister was rushed to Hadassah Hospital with a heart attack. It turned out to be a relatively mild one, and the doctors indulged his doggedness by allowing him to work minimally behind a curtained-off corner in the coronary ward, which he shared in semi-privacy with eight other patients. Summoned to his bedside, I found him propped up reading cables. His pajama-clad shoulders were bowed and his cheeks sallow, but his eyes were as sharp as ever.

“

Hosht du gehert aza meisa?

” [Did you ever hear of such a thing?] he asked me impishly, in colloquial Yiddish. “Lord Carrington has the chutzpah to tell me what I should be doing here in my own capital. I read it in a press report from London this morning.”

The British foreign secretary and the Israeli prime minister had, by this time, arrived at a no-exit stalemate of chronic dislike for one another.

“I shall write him a letter!” said Begin, and on the spot he began dictating to me a furious reprimand, essentially telling Lord Carrington to mind his own business, and repeating much the same thing as he had said to one of the journalists outside Number 10, when he had called on Mrs. Thatcher.

“Open your bible, Lord Carrington,” he dictated, “and read the First Book of Kings, chapter two, verse eleven, where you will find that King David moved his capital from Hebron, where he had reigned for seven years, to Jerusalem, where he ruled for another thirty-three years, and this at a time when the civilized world had never heard of London.”

Released from hospital ten days later to recuperate at home, Begin seemed unfazed that eleven of the thirteen foreign embassies in Jerusalem

–

including the Dutch, which had been the first to open an embassy in Jerusalem – had withdrawn to Tel Aviv, in protest against the Knesset bill. Begin also received a fourteen-page letter from President Sadat which included a sharp protest against the Jerusalem bill. Annoyed though the Egyptian leader was, he nevertheless graciously opened with a solicitous inquiry about Mr. Begin’s health after his heart attack. These were not empty words; as unlikely as the pairing of these two men was, they had, by now, taken a genuine liking to each other.

In his reply, which Begin drafted that night, he began on an equally personal note, marveling with intense lyricism at the fragility of the human heart. He wrote:

May I tell you something of my thoughts during the illness which suddenly befell me? My good doctors put me under a big machine, made in Israel, unique in its sophistication. They made a photo of my heart and decided to show it to me. So, what is the human heart? It is, simply, a pump! God Almighty, I thought to myself, as long as this pump is working, a human being feels, thinks, speaks, writes, loves his family, smiles, weeps, enjoys life, gets angry, gives friendship, gets friendship, prays, dreams, remembers, forgets, forgives, influences others, is being influenced by other people

–

lives! But when this pump stops, one is no more. What a wonder is the cosmos and the frailty of the human body, without which the mind, too, becomes still, helpless and hapless. Therefore, it is the duty of every man who is called, to serve his people, his country, humanity, a just cause, to do his best

–

as long as the pump pumps.

Having delivered himself of these musings, he delved into the substance of the Egyptian president’s letter, gently rebuking him for insinuating that he had misled him on the matter of Jerusalem:

You will, I hope, forgive me for this quasi-philosophic introduction, but it is relevant. Both our nations yearn for peace. It is in this spirit, and for the sake of clarity, that I must make several

corrections

in your detailed letter…You will agree with me that none of our meetings consisted of a monologue, either by you or by me. We conducted a mutual dialogue. You spoke, and I responded. I spoke, you responded. Let us therefore refresh our memory of the things we spoke about.

In your letter to me, you write, “You will recall that I agreed [in El Arish] to provide you with water that could reach Jerusalem, passing through the Negev. You, however, misunderstood the idea by saying that the national aspirations of your people are not for sale.”

Mr. President: I believe that were you to recreate in your mind our short dialogue at El Arish you will agree that: (a) you suggested to me bringing water from the Nile to the Negev Desert. You never once mentioned bringing water to Jerusalem; (

b)

I never said that the national aspirations of my people are not for sale. I would never use such language in our exchanges. You took the initiative by making a double proposal. You said: “We must act with vision. I am prepared to let you have water from the Nile to irrigate the Negev,” and you also said, “let us resolve the problem of Jerusalem, because if we solve this problem we solve everything.” To which I responded: “Mr. President, water from the Nile to the Negev Desert

–

a great idea, indeed a great vision. But we must always distinguish between moral and historical values, which is the matter of Jerusalem, and material advances, which is the matter of watering the Negev. So let us separate the two

–

Jerusalem on the one hand, and water from the Nile to the Negev on the other.”

He then went on to catalogue in immense detail the number of times he had emphasized his principled and consistent refusal to put Jerusalem on the negotiation table, and objected to the intimation that under Jewish sovereignty the religious rights of Muslims and Christians could not be guaranteed. Warming to that topic, he sermonized:

We know that from the point of view of religious faith, Jerusalem is holy to Christians and Muslims, but to the Jewish people Jerusalem is their history for three millennia, their heart, their dream, the visible symbol of their national redemption.

Anwar Sadat was not at all receptive to this lecture. Two weeks later he wrote a thirty-five page retort, much of it a recapitulation of his

previous

epistle, but introduced now by a lengthy discourse on the religious imperative which had inspired all his negotiations. His inspiration, he wrote, was stirred while on a visit to Mount Sinai. Begin was so intrigued by this that he invited Deputy Prime Minister Yigael Yadin, Foreign Minister Yitzhak Shamir, and Interior Minister Yosef Burg to his home, to hear their impressions of the opening paragraph of the Sadat letter, which he read out to them: