The Psychopath Inside (7 page)

Read The Psychopath Inside Online

Authors: James Fallon

I wondered how the functioning of the frontal lobe, specifically the lower (ventral) and medial (along the midline) portions of the prefrontal cortex, would lead to some of the traits generally seen in psychopathy. A psychopath has a poorly functioning ventral system, usually used for hot cognition, but he can have a normal or even supernormal dorsal system, so that without the bother of conscience and empathy, the cold planning and execution of predatory behaviors becomes finely tuned, convincing, highly manipulative, and formidable. Because psychopaths' dorsal systems work so well, they can learn how to appear that they care, thus making them even more dangerous.

The other brain areas related to psychopathologies are the amygdala in the anterior inner region of the temporal lobe, the hidden insula, bridging the orbital cortex and anterior temporal lobe, and the cingulate and parahippocampal cortices, also connecting the prefrontal cortex and amygdala in a looping fashion. These areas of the brain of the psychopath were later shown in a thorough and well-done series of MRI studies in 2011 and 2012 by Kent Kiehl's research group at the MIND Institute at the University of New Mexico.

As discussed before, all of these are lumped together as the

limbic cortex, or cortices associated with the processing and elaboration of emotion. These areas are critical to understanding the psychopathic brain, for these, as well as the orbital and ventromedial prefrontal cortices, are maldeveloped or have sustained early damage. This finding was not a surprise to me, as all these brain areas had been implicated in individual syndromes related to lack of inhibition, sexual hyperfunction, and problems with moral reasoning. What was surprising was that psychopaths all showed these brain areas with lower activity, while other types of criminals, for example impulsive murderers, had a different pattern where one of these areas would show lower function, but not all the areas together.

For example, in impulsive people there is often a malfunctioning of the orbital cortex, and in hypersexual and rage-prone people there is often amygdaloid dysfunction. In people with parahippocampal and amygdala damage, one often finds inadequacies in emotional memory, sexuality, and social behavior, and in people with cingulate dysfunction, there can be problems with mood regulation and behavioral control. But the pattern of decreased functioning across the entire complex of these limbic, prefrontal, and temporal corticesâwhether due to prenatal development, perinatal maternal stress, substance abuse, direct trauma, or a severe rare combination of “high-risk” genesâappeared unique to the psychopath's brain.

No one had reported on the combination of prefrontal and temporal lobe underfunction, I noticed, and this motivated me to try my theory out on professional audiences, even though I was

not an expert in the area at that time. It was a new field and no one had established expertise. But given my neuroanatomical background, I was trained to visualize and explain previously unknown brain circuits in the normal and abnormal brain. I began giving talks on the subject in 2005 to several medical research universities and law schools in the United States, Europe, and Israel, and to the National Science Foundation Mathematical Biosciences Institute. I also gave one to the Moritz College of Law, after which they invited me to write my first paper on violent psychopathsâthe one I was working on the day I discovered my own scan. I wanted to organize my own thoughts on what makes these nasty fellows tickâand then explode into the worst kinds of violence.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

In 2005, I was also doing multiple studies on Alzheimer's disease. For one study, I needed to analyze a number of healthy comparison subjects. I figured we might as well look at a whole family, for an added dimension. So I scanned the brains of my mother, my aunt, three of my brothers, Diane, me, and our three kids. Fortunately everyone turned out fine. At least on the Alzheimer's front.

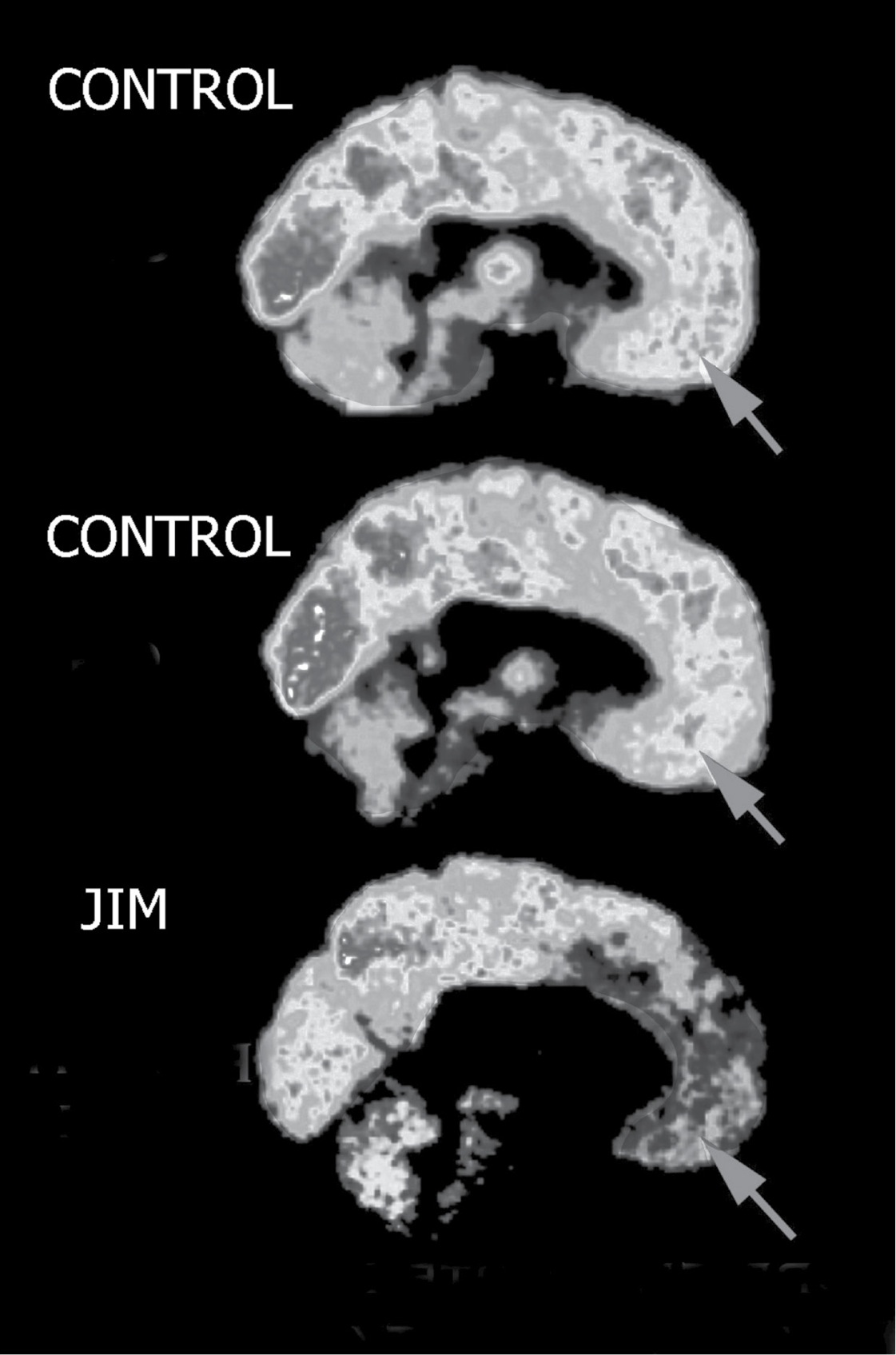

This was when the realization mentioned at the beginning of this book occurred. Looking at my family's scans, I saw one that I thought had been mixed in from the psychopathic killers' scans. It turned out to be my own. I had the trademark inactivity in the orbital, ventral, and temporal cortices as well as connecting tissue.

FIGURE 3E

: My PET scan (with two controls).

My first reaction: “You've got to be kidding me.” It blew me away. Then I just laughed. I said to myself, “Oh, I get the joke.” If you were asked over the years to look at killers' brains and found a pattern to them, and then found out you had the same pattern, that's funny. If I'd thought for a moment that I really was a psychopath, I may have reacted more soberly. But I didn't.

One reason for my denial was that, despite my research into the brain and behavior, I had very little understanding of what a psychopath was, since psychopaths weren't the focus of my lab. In my mind, they were mostly violent, unstable individuals who lacked empathy and thrived on manipulation. Love me or hate me, I was not a criminal. My brain may have looked a lot like those of the murderers I'd been studying, but I had never killed or ruthlessly assaulted anyone. I had never fantasized about committing violence or doing harm to another individual. I was a successful, happily married father of threeâa pretty normal guy.

Most of my colleagues wouldn't find out about my scan for three more years, but I mentioned it in a few of my talks on psychopathy. People said, “That's pretty wild, but what does it mean?” They couldn't process it. I obviously was not a psychopathic killer like the people I'd been studying, so no one made a big deal out of it.

I mentioned the scan to my family, but they're not scientists. They just said, “Oh, interesting.” Diane told me, “I've known you my whole life, and you've never hit me. That scan is curious, but the proof is in the pudding. Sure, you've got a lot of bad behaviors, but you're not that.”

And I didn't question her.

Bloodlines

A

lthough I wasn't worried I was a psychopath, the revelation that my own scan fit perfectly with the pattern of the scans of the psychopathic killers did give me reason to pause. I'd been so sure I'd discovered something profound that would help us better understand what makes a psychopath a psychopath, but the disconnect between my brain pattern and my behavior might imply that my theory of the psychopath brain was wrong, or, at the very least, incomplete.

In December 2005, two months after I discovered my abnormal brain scans, my wife, Diane, and I hosted a barbecue for our immediate family one Sunday in our backyard. As I was grilling various meats and veggies, my mother, Jennie, pulled me aside. “I hear you've been going around the country talking about murderers' brains,” she whispered. She knew I'd given a few lectures in which I mentioned that my own brain looked just like a killer's. “I think there is something you should look at.”

She had my full attention.

“Your cousin Dave mentioned a new historical book that was published, and it is about our family. Well, actually, it's about your

father's family.” My cousin David Bohrer, a no-frills, intellectual, and nimble-witted newspaper editor, is an avid family genealogy buff and came across this book in his research. He and I had discussed family history for years, and he had mentioned the book to me without any particular value-added heads-up concerning what it was about. I had ordered it a few months before but hadn't bothered to read it.

“I know about the book, Ma, but haven't had time to read it yet.”

“Why not?”

“Please, Mums, I'll look at it after dinner.”

I knew the bum's rush I was giving my mother wasn't going to keep her at bay for long. As a teenager, she had successfully broken through the otherwise impenetrable defenses of Elsa Einstein, wife of Albert, after seeing her on the streets of Poughkeepsie, to gain favor for her husband's autograph. Sixty years later I had lost her in a crowd outside the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, only to track her down fifteen minutes later duking it out with radio rock jock Rick Deesâshe thought modern-day music was much too loud and the lyrics disgraceful and wanted to tell him about it. I had also seen her lecture our family friend George Carlin several times about the use of profanity in his acts; he was, after all, plenty funny enough without having to resort to such cheap and vulgar word games, Jennie said. This diminutive Sicilian, who was still, at eighty-nine, a sharp-tongued

principessa

, would not be easily put off by her son's disinterest in her book recommendation. But, out of respect for

the time-honored rule that a meal cooked properly comes first, she relented.

A half hour after finishing dinner I stole away to my office for a bit and sat down to a double espresso and a glass of black anisette, with the obligatory thirteen coffee beans thrown in. As I munched on the beans and sipped the coffee and liqueur, I skimmed the book. It was called

Killed Strangely: The Death of Rebecca Cornell

, by Elaine Forman Crane, and it detailed the murder of seventy-three-year-old Rebecca Cornell by her forty-six-year-old son, Thomas, in 1673. This was one of the first cases of matricide in the American colonies. (The Cornell family tree is of some general interest to an American history buff, as Rebecca is an ancestor of Ezra Cornell, the founder and namesake of Cornell University.)

Rebecca lived in a large house on a one-hundred-acre plot along the Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island with Thomas and his family. One night after dinner she was found charred and smoldering near the fireplace in her bedroom, almost unrecognizable. Originally the death was decreed an “Unhappie Accident,” but Rebecca's brother was soon visited by an apparition suggesting foul play. Thomas, financially dependent on his mother, had not always gotten along with her and was at times abusive. Rebecca's body was exhumed for a closer examination, and a suspicious wound was found in her stomach, the result of a possible stabbing. Despite weak evidence, Thomas was convicted and hanged.

My mother wasn't just interested in Rebecca's story because she had warped taste in entertainment. According to David,

Rebecca Cornell was our great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandmother in our patrilineal line. And it turned out that Thomas wasn't the only murderer in the Cornell clan. Rebecca, the book pointed out, was also a direct ancestor of Lizzie Borden, the putative ax murderer accused of killing her father and stepmother in 1892. That made Borden, according to David, our cousin. The book reported that between 1673 and 1892, there would be a handful of other murderers and suspected murderers in our patrilineal line, each one of whom had been accused or convicted of killing a close family member. Rebecca's descendant Alvin Cornell murdered his wife, Hannah, in 1843, using first an iron shovel handle to strike her, then a razor to slit her throat. The Cornells' penchant for killing their own, I mused, was damned civic-minded of our lot, and happily, and somewhat conclusively, the trail seems to have run cold at the end of the nineteenth century, making me and my father several generations removed from

that

side of the family.

David and our other cousin Arnold Fallon have researched our family tree with great energy and expertise. Through their tireless genealogical efforts, including visits to cemeteries scattered throughout New England, New York, Kansas, and California, they continue to discover new and juicy family tidbits. In 2011 and 2012, they found two other paternal lines of grandfathers where further mayhem is still being uncovered, including one line of suspected and convicted murderers (for a total of seven in the family, two of them women), and one line of grandfathers with a penchant for leaving their wives and families for either other

women or completely unknown reasons. In both of these lineages, and the Cornell line, our male ancestors were unkind or downright homicidal to people in their immediate families only, never to strangers.

Going further back, my distant grandfather King John Lackland (1167â1216) is known as the most brutal, and hated, of the English monarchs, in spite of the fact that he signed one of the most important antimonarchical documents of all time, the Magna Carta. John was quite the all-pro prick, said to have lacked scruples (something a close friend once said about me), been treacherous, and to have a “puckish” sense of humor (something my uncle Bob once said of me). He had very high energyâhypomania if not maniaâand was highly distrustful, unstable, cruel, and ruthless. A near-contemporary of his said, “John was a tyrant. He was a wicked ruler who did not behave like a king. He was greedy and took as much money as he could from his people. Hell is too good for a horrible person like him.” But kind things, almost, have been said about him, too. In

King John: England's Evil King?

, the historian Ralph Turner wrote, “John had potential for great success. He had intelligence, administrative ability and he was good at planning military campaigns. However, too many personality flaws held him back.”

John's father, Grandpa King Henry II (1154â1189), was like John in that he also went into violent rages. At times they got so pissed off that they foamed at the mouth. Henry was killed by his son. Grandpa Henry III and Grandpa Edward I, like King John, were also known to be a bit aggressive, impulsive, and

mean-spirited, and all four were brutal toward Jews. Henry III made Jews wear a badge of shame in public, and Edward I expelled the Jews from England in 1290, but not before executing three hundred of them. Edward was feared one-on-one. He was big, powerful, and aggressive and was referred to as a leopard (in a derogatory way) in “The Song of Lewes” in 1264. The historian Michael Prestwich wrote that the dean of St. Paul's confronted Edward over taxation and died (somehow) on the spot at the king's feet, so he may have been murdered by hand, although I have never seen that confirmed.

Diane and I visited a “family” castle (Caerphilly Castle) in Wales in 2004. This was the roost of Grandfather Gilbert de Clare. He also massacred Jews (1264) at Canterbury. Another bad guy in this same line is John Fitzalan. In one campaign he rested up in a nunnery, where his men (and he?) raped all the women inside, then ransacked the neighborhood in Brittany. Right after this, on his boat just off the coast, some of his men became frightened of a storm, so he murdered them. This is only a sampling, but suffice it to say I do not come from a line of mensches.

I knew my mother was pleased by these developments. Jennie, whose full Sicilian name is Giovannina Giuseppina Salvetrica Sylvia Scoma, is the daughter of Sicilian immigrants who, like many others who had come to America to make their way up in the world, had engaged in some dubious activities over the course of their lives. My grandfather Tomas held various respectable jobs while my mother and her siblings grew up: court interpreter,

barber, pinsetter, musicianâbut even after he moved the family from Brooklyn, where my mother was born, to Poughkeepsie, he worked each week in Brooklyn running numbersâthat is, orchestrating an illicit lotteryâand selling enough bootleg merchandise to open his own restaurant. This being the Prohibition era, my mother and her brother and three sisters supported their father's entrepreneurial endeavor by bootlegging beer. My father and his family, unsuspecting of their own unsavory roots, loved to tease my mother about her past. So I wasn't surprised to notice a devilish twinkle in Jennie's eyes as she told me about my father's bloodthirsty ancestors.

As with my brain scan, the discovery of this bookâand, later, the rest of the historyâdidn't trouble me too much. To me, it was the sort of revelation one might even brag about, akin to discovering your family is made up of more horse thieves than blue bloods.

I also knew that ancestry is not genetics, and, given the amount of dilution of genetic impact at each mixing generation, it is hard to make a case that such a long and checkered lineage over centuries would determine why and how a particular person would behave, and misbehave. Nonetheless, in our family we know of at least two lines of killers and one line of wife abandoners. This type of genetic parlor game makes one wonder whether a slight tendency for some traits might percolate through so many generations to the present. Complicating the story, my father, my grandfather Harry Cornell Fallon, and two uncles who fought in World War II were conscientious objectors, but nonetheless were

medics in battles at Iwo Jima, New Guinea, and New Caledonia. I should point out, however, that my grandfather loved to brawl. Also, in my own generation of brothers and cousins, at least five are aggressive and fearless boxers and street fighters. They actually

like

to fight, and will even take on several people at a time by themselves. These hombres are fearless and aggressive. But they are also great partyers, funny, and smart.

My family history would take on a new level of gravitas when I started to learn about my own genes. As part of the Alzheimer's brain scan study, my lab had taken blood samples for genetic analysis. And as soon as I saw my own scan, I decided we should check those samples for aggression-related traits.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

How do genes affect behavior? To begin to answer this question, it's important to understand some basics about genetics.

There are approximately twenty thousand genes in the human genome. The genes are located in forty-six chromosomes (twenty-three pairs), one set in the pairs derived from the mother, one set from the father, in the nucleus of most cells of the body. The only cells that don't contain all forty-six chromosomes are the germ cells in the testes or ovaries, each of which has twenty-three chromosomes, or half the number in the somatic cells. Cells that contain all forty-six chromosomes are called diploid cells since they contain both pairs, while germ cells are called haploid.

Chromosomes are composed of DNA, the master blueprint of a cell. DNA is coded on the sequence of four different chemicals called bases. The bases sit in pairs with T (thymine) coupled with

A (adenine) and G (guanine) coupled with C (cytosine). The forty-six-chromosome (diploid) genome contains over six billion base pairs. Sequences of base pairs, called genes, code for and produce gene products such as proteins. If just one of the base pairs is altered by mutation, say from ultraviolet damage, a virus, or cigarette smoke, the resulting protein will be aberrant, and usually faulty.

Some of these mutations are not fatal and are actually kept by the cells and the population. These are called single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs. If the incidence of the change is found in less than 1 percent of the population of humans, it is called a mutation; if more than 1 percent, it is typically called an SNP. There are about twenty million SNPs found in humans, and they account for many differences in the appearance and behavior of people, from curly hair to obesity to drug addiction. It is these SNPs where the hunt for genetic “causes” of traits and diseases has focused since the 1990s.

Other important alterations to the genetic code involve so-called promoters and inhibitors, pieces of genes that regulate the gene's ability to make products. Some of these products regulate the behavior of neurotransmitters. So promoters and inhibitors are like the gas and brake pedals of a gene as they control the delivery of neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine in the brain. For serotonin, implicated in depression, bipolar disorder, sleep and eating disorders, schizophrenia, hallucinations and panic attacks, as well as psychopathy, the breakdown enzyme is MAO-A. MAOA, the gene that produces this enzyme (and lacks its hyphen),

has a promoter that comes in either a short form or a long form. The version of the MAOA gene with the short promoter has been associated with aggressive behavior and is called the “warrior gene.”

There are probably twenty to fifty or more SNPs involved in causing most diseases. Therefore, statements that the warrior gene “causes” aggression, violence, and retaliation raises the hackles of geneticists, since there are probably dozens or more “warrior genes” in people who are particularly violent. But even the simple diseases (called Mendelian diseases, after the godfather of genetics, Gregor Mendel)âlike cystic fibrosis, which is caused by a single mutation in the gene that codes for the chloride channel in cell membranes regulating water balance in the lungs and gut and glandsâcan appear as fifty different disorders in fifty different individuals with the disease. In the case of cystic fibrosis, that single chloride channel mutation affects other cellular and organ components. The gene-gene interaction, or more correctly gene productâgene product interaction, is called epistasis, and this effect must also be considered when determining the causes, symptoms, and cures for diseases of all kinds, even psychiatric disorders.