The Rags of Time (23 page)

Authors: Maureen Howard

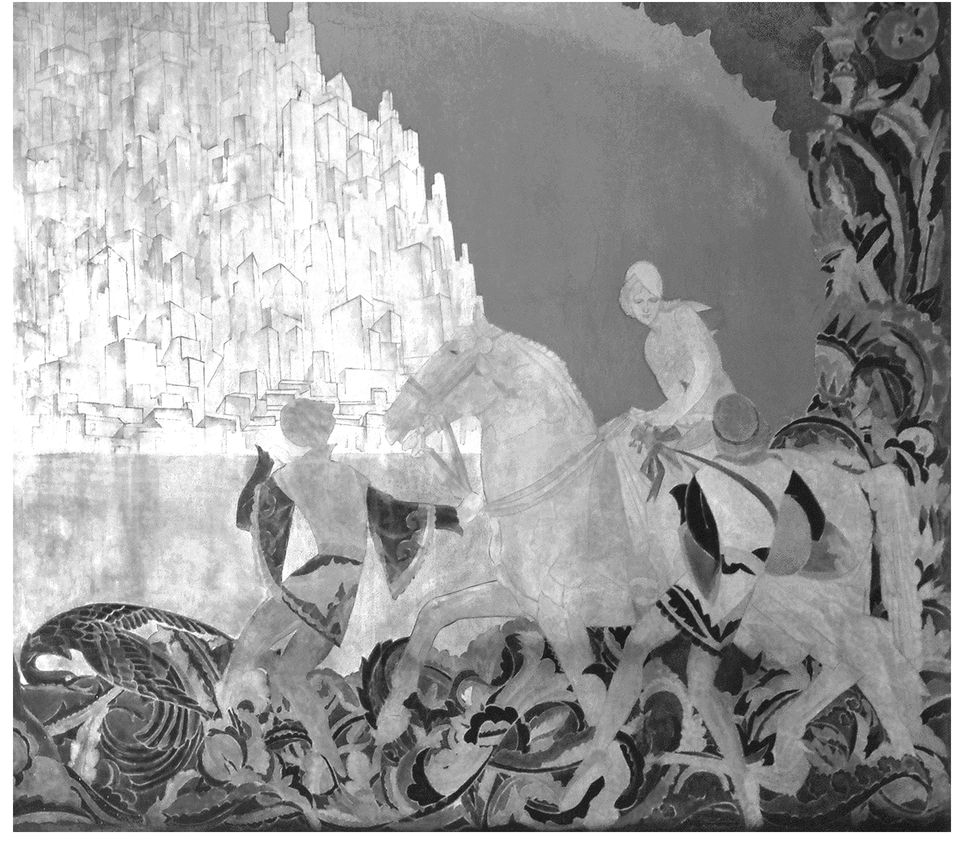

El Dorado

LITERARY WALK

Unfinished business, the popular poet, Fitz-Greene Halleck:

Green be the turf above thee,

Friend of my better days!

None knew thee but to love thee,

Nor named thee but to praise.

Friend of my better days!

None knew thee but to love thee,

Nor named thee but to praise.

Tears fell, when thou wert dying,

From eyes unused to weep,

And long where thou art lying,

Will tears the cold turf steep.

From eyes unused to weep,

And long where thou art lying,

Will tears the cold turf steep.

And so forth, elegy for his friend and collaborator, John Rodman Drake. Halleck—journalist, humorist, poet, banker and in that role confidential agent to John Jacob Astor. He moved in with the lonely millionaire, regretted the loss of his muse:

The power that bore my spirit up

Above this bank-note world—is gone.

Above this bank-note world—is gone.

But retired to Guilford on Long Island Sound, wrote

Connecticut,

a long, now and then amusing poem that reflects nothing of the industrial state where I was born, where the manufacture of guns and invention of the cotton gin were to play significant roles in the Civil War. Nevertheless, ten years after his death (the designated passage of time to confirm posterity by Order of the Park Commission), Halleck was installed on Literary Walk. One of our forgettable presidents, Rutherford B. Hayes, and Frederick Law Olmsted in attendance.

Connecticut,

a long, now and then amusing poem that reflects nothing of the industrial state where I was born, where the manufacture of guns and invention of the cotton gin were to play significant roles in the Civil War. Nevertheless, ten years after his death (the designated passage of time to confirm posterity by Order of the Park Commission), Halleck was installed on Literary Walk. One of our forgettable presidents, Rutherford B. Hayes, and Frederick Law Olmsted in attendance.

On the other hand, Shakespeare, encircled in late blooming mums, is smaller in scale than Halleck, Robert Burns, and Walter Scott, though he’s afforded a more decorative plinth to set him above us. The inline skating

proficienados

on their way to the plaza fronting the bandstand to compete in splits, flips, airborne waltzes know the Bard and a fragment of verse, if only lines from a movie.

Maria! Say it soft and it’s almost like praying. . . .

proficienados

on their way to the plaza fronting the bandstand to compete in splits, flips, airborne waltzes know the Bard and a fragment of verse, if only lines from a movie.

Maria! Say it soft and it’s almost like praying. . . .

Oh, leave them alone; don’t heckle, lick your old chops at their presumed ignorance while your fingers, a touch arthritic, fumble at the cell phone, which begs for your password. The call home aborted.

In the Park,

all I meant to say. Obsessed with the Greensward, I plump myself down in its stories, the neat rectangle of its map morphing into the uncertain turns and loops of the natural world, slopes and summits plotted.

In the Park,

all I meant to say. Obsessed with the Greensward, I plump myself down in its stories, the neat rectangle of its map morphing into the uncertain turns and loops of the natural world, slopes and summits plotted.

As I descend to the Terrace, the Lake appears two dimensional against a painted backdrop of an enchanted forest as in

Midsummer Night’s Dream,

but we are well into November. Movietime, Mickey Rooney played Puck, but who was Titania, Queen of the Fairies?

Midsummer Night’s Dream,

but we are well into November. Movietime, Mickey Rooney played Puck, but who was Titania, Queen of the Fairies?

Come, sit thee down upon this flow’ry bed,

While I thy amiable cheeks do coy,

And stick musk-roses in thy slick smooth head,

And kiss thy fair large ears, my gentle joy.

While I thy amiable cheeks do coy,

And stick musk-roses in thy slick smooth head,

And kiss thy fair large ears, my gentle joy.

Many trivia questions remain unanswered. You remind me our little life’s not a game show. No buzzer of defeat. No cash prizes. My adventures in the Park across the way from our apartment seem all too solitary, enacted in the geography of my imagination. Virginia Woolf gave up on a friend who was addicted to Solitaire, laying out the cards in a dreary game the Brits call Patience. Well, I have no patience with life dealt out in med milligrams, scaled down to my daily walk: to the yield of small encounters, a scrapbook of facts and fables, though I have included you along the way, begged your advice, as in:

What am I to do with terra incognita above 96th Street?

What am I to do with terra incognita above 96th Street?

You said:

Anita Louise played Titania.

Ashamed you knew that, then:

There’s something odd going on with you. Some evasion.

Anita Louise played Titania.

Ashamed you knew that, then:

There’s something odd going on with you. Some evasion.

Dusting me off, you switch to an old story, this day’s further deflation of the dollar against the euro, then recall how we lived it up, traveled on two cents plain when we were kids. Our mighty dollars cashed in on the black market.

Expensive gelato in the Piazza Barberini.

Raspberry tart, rue Monsieur-le-Prince.

A hundred bucks sent from home . . . I bought pantomime figures in the dusty bookshop on my way to the British Museum.

Switching channels, you assume the editorial voice:

Gold will top

$800

an ounce. The banks have gone begging.

Gold will top

$800

an ounce. The banks have gone begging.

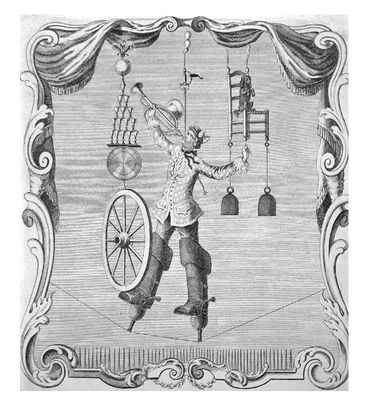

My tightrope walker, jugglers, clowns have never faded all these years. I love those theatrical folks trained to amaze, take chances.

We talk a Mad Hatter’s babble avoiding what we intend. If we didn’t speak at cross purposes, I’d admit that I’m silenced by candidates now up and running, not one of them reflecting my angst as night by nightly news broadcasts our failure. My mistrusts of Sunday morning pundits. Last week, fellow with the plastic hair had the buzz:

The war’s not front page.

His easy skip to inflation. At my wrath, you pleasantly turned to the commodities market. Copper, corn, oil $$$ a barrel, the Chinese paying top price for iron. Tiffany & Co. interest in gold digging, though seven hundred thousand pounds of waste a day gives the corporation pause. Gold has nothing to do with my explorations in the Park written on devalued paper. No mention of uranium, or my angry outburst last month against the war, carrying on like a braless girl lost in Woodstockian fields of love is the answer. Your voice dipped to a whisper, a calming suggestion—

El Dorado.

The war’s not front page.

His easy skip to inflation. At my wrath, you pleasantly turned to the commodities market. Copper, corn, oil $$$ a barrel, the Chinese paying top price for iron. Tiffany & Co. interest in gold digging, though seven hundred thousand pounds of waste a day gives the corporation pause. Gold has nothing to do with my explorations in the Park written on devalued paper. No mention of uranium, or my angry outburst last month against the war, carrying on like a braless girl lost in Woodstockian fields of love is the answer. Your voice dipped to a whisper, a calming suggestion—

El Dorado.

Seems a year since my brother calmed me down.

A little warm milk before bedtime, Mimi. Do Columbus.

A little warm milk before bedtime, Mimi. Do Columbus.

And now you accused me of evasion, ask,

How was your day?

Drama queen no more, I report that I gave full attention to my computer, then took the grandchildren to the playground that lies in the earthworks across the street. Longitude and latitude same as always on CPW, though you still refer to the 8th Avenue Subway. You grew up in this city. I did not. You climbed the Park’s massive rock formations with the janitor’s boy before he was thrown out of PS 6, years before Bimbo, your nefarious playmate, had a record, before they sent you to the private school with proper teams, playing fields. No more make believe in the Park above 96th—bang, bang you’re dead—no private adventures.

How was your day?

Drama queen no more, I report that I gave full attention to my computer, then took the grandchildren to the playground that lies in the earthworks across the street. Longitude and latitude same as always on CPW, though you still refer to the 8th Avenue Subway. You grew up in this city. I did not. You climbed the Park’s massive rock formations with the janitor’s boy before he was thrown out of PS 6, years before Bimbo, your nefarious playmate, had a record, before they sent you to the private school with proper teams, playing fields. No more make believe in the Park above 96th—bang, bang you’re dead—no private adventures.

Yes, I spent my fish-and-chips pence on comic cutouts of Columbine and Pierrot, those quarrelsome lovers, and prints of my tightrope walkers who never worked with a net.

I’m a girl from the circus town of Bridgeport, where my grandfather, getting on with his life, carted water and hay—seventeen dollars for the season—to elephants shivering in Barnum’s winter quarters, longing for dust baths and a wallow in warm African rivers.

I’m a girl from the circus town of Bridgeport, where my grandfather, getting on with his life, carted water and hay—seventeen dollars for the season—to elephants shivering in Barnum’s winter quarters, longing for dust baths and a wallow in warm African rivers.

See here, on the bill of sale: ALL GOODS SOLD AT PURCHASERS RISK.

Now, wasn’t that smart of Grandpa?

Now, wasn’t that smart of Grandpa?

He left out the apostrophe.

He never made it to eighth grade. You know there’s a statue of the Hatter in the Park. He smirks while Alice presides for a sane moment.

The kids?

Yes, after school with the children. We’re lucky to have them nearby. Just suppose we were in some sunny place with elder persons? Golf cart gliding us about the links, Happy Hour for Seniors, the lively arguments of a book club . . .

Come off it. The playground in your Park?

Yes, the one with decks, child-safe. Nicholas dangling from a rope swing—no hands!

So, a full report: The playground was desolate, the bench I sat on littered with leaves that should have fallen weeks ago. The lone baby tender on the phone neglecting her charge, a bandy-legged toddler eating cookies coated in sand. Kate, beyond playground, stood aloft on the deck, my binoculars aimed at our building, the windows catching the brass light of sundown.

Hoping to see their terrarium.

So, a full report: The playground was desolate, the bench I sat on littered with leaves that should have fallen weeks ago. The lone baby tender on the phone neglecting her charge, a bandy-legged toddler eating cookies coated in sand. Kate, beyond playground, stood aloft on the deck, my binoculars aimed at our building, the windows catching the brass light of sundown.

Hoping to see their terrarium.

She can’t see round corners.

That’s worth a fleeting smile. Our argument is winding down. True, we live in the rear of our building. With an angling of the head pressed to the window, I am afforded a partial view of the asphalt entrance to the Park, where you fear I’ve invested unwisely in a bear market of legends, unreal estate of my last place on earth. As for Kate, she wanted to spritz their terrarium, the brandy snifter in which they have created an alternate world—tropical, lush as the virgin forests of Guiana, which reminded Columbus of Valencia. You know perfectly well that it sits on our windowsill sweating the seasons.

That was my day. Now will you answer my question? What’s above 96th?

You’re back to the weak dollar, to gold mined mostly for jewelry. Whole hillsides destroyed, wetlands reduced to ash for rings on our fingers, bells on our toes. Not mine, no way José in Peru with lungs collapsing from tons of toxic waste. I am sanctimonious, but my outrage at those who think it’s OK to slam a prisoner’s head into water, bobbing for rotten apples, folks, doesn’t have the old huff and puff. I’m reduced to a litany of complaints. You have not separated paper from plastic while I have taken bottles to the bottle people who live on the returns of our trash. And have you noted that the smirk of Cheney’s smile has dipped to new lows? Never called Veep. That would lend him a pinprick of cozy: and the detained may never come to trial. The deflation of their captors is the best we can—I can—hope for, the stale breath of their dark secrets, slow wheeze of their hot-air balloon, the sorry spectacle of its bladder on

the green breast of the new world

.

Its vanished trees . . .

the green breast of the new world

.

Its vanished trees . . .

At the end of

The Rings of Saturn,

Sebald’s walking tour of the east coast of England, having embraced the near and far reaches of history, personal and public, he returns to home and garden, recalls the elms devastated by the Dutch elm disease:

The Rings of Saturn,

Sebald’s walking tour of the east coast of England, having embraced the near and far reaches of history, personal and public, he returns to home and garden, recalls the elms devastated by the Dutch elm disease:

One of the most perfect trees I have ever seen was an almost two hundred-year-old elm that stood on its own in a field not far from our house. About one hundred feet tall, it filled an immense space. I recall that, after most of the elms in the area had succumbed, its countless, somewhat asymmetrical, finely serrated leaves would sway in the breeze as if the scourge which had obliterated its entire kind would pass it by without a trace; and I also recall that a bare fortnight later all these apparently invincible leaves were brown and curled up, and dust before the autumn came.

This year, next year . . . will mark the hundred years since the elms were planted to arch over the Mall. With great care and expense, many are still standing, some replaced, each tree endowed, money down against disease. Olmsted understood the American elms’ formality, the grandeur of their welcoming arch to the people of the city, high and low. Saplings demand patience.

In the morning you leave a report on the front hall table. It is a research update on the

Eldorado Gold Corporation.

So we spar, paper-doll lovers, kiss and make up.

Product development toward year end. No new ounces added to the reserve.

Read as a message, I understand you would like me to nest on the sill, flourish under glass like the ferns in the children’s terrarium, and entertain no dangerous exploits above 96th Street. Stay put, here in the El Dorado. Next you may advise meditation—ooom, ooom—and renew the prescription: no exercise beyond the short walk in which I turn and see them looming, the safe towers of home. But today I’ll push on in the Park to 72nd across from the Dakota, determined to investigate the report that IMAGINE is sinking, the tiles at the edge of the magic circle sucked into sandy soil. By the time I reach Lennon’s memorial, I’m bummed out, the heavy heartbeat throbbing as I join a busload of tourists, baby boomers honoring their bonged past. And the crazies always, humming as they lay tulips round about in a mysterious pattern. I’m foolishly encouraged. IMAGINE has been shored up, as certain in this uncertain world as Radio City, Ellis Island, St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Eldorado Gold Corporation.

So we spar, paper-doll lovers, kiss and make up.

Product development toward year end. No new ounces added to the reserve.

Read as a message, I understand you would like me to nest on the sill, flourish under glass like the ferns in the children’s terrarium, and entertain no dangerous exploits above 96th Street. Stay put, here in the El Dorado. Next you may advise meditation—ooom, ooom—and renew the prescription: no exercise beyond the short walk in which I turn and see them looming, the safe towers of home. But today I’ll push on in the Park to 72nd across from the Dakota, determined to investigate the report that IMAGINE is sinking, the tiles at the edge of the magic circle sucked into sandy soil. By the time I reach Lennon’s memorial, I’m bummed out, the heavy heartbeat throbbing as I join a busload of tourists, baby boomers honoring their bonged past. And the crazies always, humming as they lay tulips round about in a mysterious pattern. I’m foolishly encouraged. IMAGINE has been shored up, as certain in this uncertain world as Radio City, Ellis Island, St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Other books

Patrick: A Mafia Love Story by Saxton, R.E., Tunstall, Kit

Some Like It Wild by M. Leighton

Minstrel of the Water Willow by Elaina J Davidson

Teresa Medeiros - [FairyTale 02] by The Bride, the Beast

Life Is Not a Reality Show by Kyle Richards

Snake Handlin' Man by D. J. Butler

Hardpressed by Meredith Wild

Saul of Sodom: The Last Prophet by Jinn, Bo

The Endless Sky (Cheyenne Series) by Henke, Shirl

The Key West Anthology by C. A. Harms