The Rape of Europa (26 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

The Baron’s lifestyle was anything but modest. Alfred Rosenberg, his real boss, had encouraged him to entertain lavishly in order to gain respect for the ERR, which was held in contempt by the regular army. The aristocratic von Behr, always attired in fancy uniforms, and his English wife did what they could to push their way into high occupation society. Goering’s influence was extraordinary. Officers who at heart condemned the confiscations were still dazzled enough to betray their consciences. This was certainly true of Dr. Bunjes, who when he was eventually fired by Metternich was immediately rehired by Goering as an Air Force officer.

Ideologue Rosenberg, whose scruples were of a different nature, was by now totally eclipsed within his own agency. On his one visit to the Jeu de Paume the only way people knew he was there, according to Rose Valland, was by the “funereal smell of the many pots of chrysanthemums which had been put around in his honor.” Being in Paris was all-important. Rosenberg assistants such as Robert Scholz who were sent periodically to check up on the outrageous goings-on got nowhere with the clever operators

sur place

, who soon discovered that they could siphon off certain works to sell for their own profit. By all accounts the atmosphere within the ERR was fraught with terrible intrigues and jealousies exacerbated by flagrant affairs carried on with the various ladies of the staff. Indeed, von Behr’s secretary and mistress, Fräulein Pütz, had to be sent home when things became too blatant; and an Eternal Triangle situation involving the reigning lady in the Paris office, her fiancé (who was a curator), and another woman badly slowed down productivity, and led to what bemused later investigators termed “hysterical slander and counter accusations.”

42

In this mad and secret scene, Rose Valland managed somehow to survive.

Her dowdy looks certainly did not invite advances from the Germans, and she was regarded by all as an insignificant administrative functionary. Her presence at the heart of this undertaking, which the Germans wished to conceal from the French, was an anomaly. Dr. Bunjes had even written in one report that “all access to the Louvre must be refused, as we do not wish the French services to know of our organization and its functions, and because it would be vulnerable to espionage.”

43

This was exactly what Mlle Valland was doing. Throughout the war she met frequently with Jacques Jaujard and his assistants, many of whom were working closely with the Resistance and through whom the Free French government was kept informed of the whereabouts of the national treasures. The museum people, like everyone else, listened late into the night to the BBC, whose programs were laced with cryptic messages to underground activists all over Europe. Thus they knew that information on the relocation of the collections to Loc-Dieu and later to other refuges had been received in London when the message

“La

Joconde

a le sourire

[The

Mona Lisa

is smiling]” came crackling through the night.

Mlle Valland’s main objective was to find out where the ERR takings were being stored in Germany. For Hitler’s and Goering’s personal acquisitions were only a part of what left France. Between April 1941 and July 1944, 4,174 cases, which filled 13S boxcars and contained at least 22,000 lots, were shipped out to the Reich.

44

There had been much discussion about where to keep all this. Posse had first suggested the basements of the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, which would hold 250 pictures or so, and which would be the most convenient place for Hitler to view them. Dr. Buchner preferred the Castle of Dachau, the folksy little Bavarian village that had become home to so many other things collected by the Reich, though he worried that its proximity to Munich would expose the paintings to bomb danger.

45

It was Hitler himself who chose the incredible pseudomedieval Castle of Neuschwanstein, built by Mad King Ludwig of Bavaria, in a remote area near the Austrian border. But so vast were the numbers of things sent there that later shipments had to be distributed to even more remote depots: Chiemsee, the Monastery of Buxheim, Schloss Nikolsburg in Czechoslovakia, and Schlosses Kogl and Seisenegg in Austria.

Four times the Germans threw Rose Valland out. The reasons were linked to the fortunes of their armies: every time an Allied landing or attack was rumored, she would be required to leave. But when the crisis had died, she would come back, talking of heating problems and maintenance, and begin her observations again. At night she took home the negatives of the archival photographs being taken by the Nazis, and had them printed

by a friend. In the morning they would be back in place. Every time there was a theft or damage she would be questioned. This, she later declared, was “very disagreeable,” but she managed to stay on. Loyal French guards filled her in on details of events in those parts of the Louvre which were off limits to her. Packers and drivers told her what they were doing. Everything was reported to Jaujard and his assistant, Mme Bouchot-Saupique. (Jaujard’s apartment, inside the Louvre itself, was a Resistance safe house, a key to which was hidden in a special place in the courtyard. Other corners of the enormous building contained caches of underground books and journals.

46

)

French resistance to German art policy was not limited to the Louvre proper. The Musées Nationaux and the Domaines had together formed a Committee of Sequestration and Liquidation which attempted to enforce the right of the French state to the “abandoned” collections, and to give the Musées the right of preemption in the case of sales of works of national interest. The idea was that the museums would liquidate the collections to themselves, thereby making them state property. The Germans allowed this for a few second-rate works, but the committee got nowhere with major ones. Nor was another ploy of any avail: the falsification of documents of donation, brilliantly done on old paper and complete with forged stamps and signatures, used in an attempt to protect the Calmann-Levy collection.

In the Unoccupied Zone they had more success. Parts of the collections of Robert, Maurice, and Eugene de Rothschild, some of which had been found in an abandoned truck on a country road, were quickly “bought” with an entirely fictitious fund of FFr 13 million appropriated by the Ministry of Finance, parent organization of the Domaines. Curators from all the major museums were invited to take their pick of hundreds of objects ranging from paintings of every school to porcelains and furniture. They quickly catalogued the works in their regular inventories, and mixed the packing crates in with the rest.

47

So persistent were the French protests against the confiscations, which came even from the Vichy Prime Minister and its Commissioner for Jewish Affairs, that they could not be ignored. The protests were addressed to General von Stülpnagel, commander of German forces in France. Encouraged by the Kunstschutz, he demanded that the ERR provide some legal basis for their activity. The resulting response must be among the masterpieces of perverted legalism.

The first document was produced in November 1941 by Gerhard Utikal, chief of ERR activities in the West, and was personally approved by Reichsleiter Rosenberg. It is a précis of Nazi philosophy which cleverly

makes use of the similar thinking of certain elements of the Vichy regime: By conquering France, the German Army had liberated it from the influence of international Jewry. The armistice made with the French people was not made with the Jews, who could not be considered the equals of French citizens, as they formed a state within a state and were permanent enemies of the Reich. The Jews, by their amassing of riches, had prevented the German people from “having their proper share of the economic and cultural goods of the Universe.” Since most of the Jews in France had come originally from Germany, the “safeguarding” of their works of art should be considered “a small indemnity for the great sacrifices of the Reich made for the people of Europe in their fight against Jewry.” The rules of war allowed use of the same methods “which the adversary has first used.” Stretching it a bit, Utikal argued that since in the Talmud it was stated that non-Jews should be regarded as “cattle” and deprived of their rights, they themselves should now be treated in the same way. The Reich had done the French a favor by not confiscating real estate and furniture along with the rest, and the French people should be grateful for the objects they had obtained through the good offices of the German armies. As for The Hague Convention, the Jew and his assets were outside all law, since for centuries the Jews themselves had considered non-Jews as outside their own laws.

48

Needless to say, this ludicrous document did not prevent further protests from the “ungrateful French.” Six months later, on orders of Goering, the ERR felt constrained to produce another justification, this time written by the less confident Dr. Bunjes. Much longer than the Utikal response, it used most of the same arguments, ornamented with childish additions which reflected the deep frustration the more brainwashed Nazis felt at their rejection by the conquered peoples they ruled. More ominous were its frequent references to “the dreaded German demands for the return of art stolen by French troops in Germany.” Blame for the complaints of the French government was placed squarely at the door of Musées director Jaujard and his staff. The closing sentence tells us all we need to know, as if there had ever been any doubt: “Only … when the Führer has made the final decision as to disposition of the safeguarded art treasures, can the French Government receive a final answer.”

49

Careful reading of the Bunjes report reveals no references to the “furniture” which the Germans, according to Utikal, had so kindly left untouched. This was for the very good reason that only a few weeks before the report was written, the ERR had started a new project: the seizure of furniture from the houses of Jews who “have fled or are about to flee, in

Paris and throughout the occupied Western territories.” The furniture would be used by the occupation administrations of the East, which after the attack on the Soviet Union had come under Rosenberg’s aegis, and where, Rosenberg lamented, “living conditions were frightful and the possibilities of procurement so limited that practically nothing more can be purchased.” Hitler thought this was a fine idea, and all commands were informed of the coming action in January 1942.

50

In Paris the odious von Behr was put in charge of this operation, which was code-named the M-Aktion (Möbel, or furniture, Project). Indeed, according to his coworkers, the whole thing was his idea.

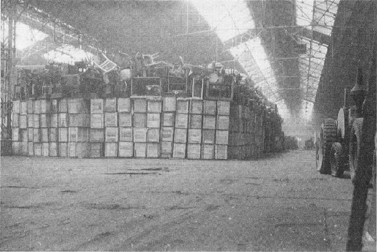

Paris: M-Aktion loot ready for shipment to the Reich, 1944

The M-Aktion marks a true low, even in the history of looting. Once again the ERR teams set out, but this time to search for soap dishes and armoires. The secret orders which initiated the process noted that “art treasures, precious rugs, and similar items are not suitable for use in the East under conditions prevailing there. They will be safeguarded in France.” Next came a message from the High Command: the confiscations were to be carried out “with as little publicity as possible. No [public] ordinance is necessary … as these measures must be represented as much as possible as requisitions or sanctions.”

51

A house-by-house check of the entire city of Paris was begun, in case

some fleeing Jews or other undesirables had not been accounted for. Some thirty-eight thousand dwellings were sealed. It was pretty complicated work: only unoccupied homes were involved, and, after consultations with the embassy, confiscation officials exempted absent Jews of many nations as well as those “who work for German firms and in forestry and agriculture, or who are prisoners of war.”

52

Food discovered on the premises was sent to the Wehrmacht; beds, linens, sofas, lamps, clothes, etc., were checked off on specially printed forms. A French organization, the Comité Organisation Déménagement, was set up and made responsible for measuring doorways, talking with concierges, packing, transporting, and finding railcars for the loot. The Union of Parisian Movers was forced to supply some 150 trucks and 1,200 workers a day for the operation.

The Germans were responsible for deciding what

not

to take, such as “objets d’art, books, wood, coal, wine and alcohol, empty bottles, etc.” They were also supposed to supervise the French railroads so the process would not be obstructed through “inertia and ill-will.”

53

Everything except art, which was sent to the Jeu de Paume, was first taken to a huge collecting area for sorting. Due to increasing acts of sabotage by the French workers, the camps were fenced off and seven hundred Jews “supplied by the SD” were interned therein, divided into groups of cabinetmakers, furriers, electricians, and so forth, and set to work processing and repairing the incoming goods, which passed by them on a conveyor belt.

Other books

The Merry Month of May by James Jones

Mona Lisa Overdrive by William Gibson

Listen To Me Honey by Risner, Fay

The Root of All Evil (Hope Street Church Mysteries Book 4) by Ellery Adams, Elizabeth Lockard

Ghost of a Chance by Kelley Roos

Dirty Little Secret (Dirty #1) by Amber Rides

The Geography of You and Me by JENNIFER E. SMITH

Calling Me Home by Louise Bay

Ride by Cat Johnson

Damaged by McCombs, Troy