The Rape of Europa (61 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

The gentlemen at Yalta had not specified who would actually do the work in occupied Germany. Roosevelt, wanting to bring the troops back as soon as possible, returned to his visions of a civilian occupation government and offered the post of High Commissioner of Germany to Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy. But McCloy knew that it would take a military presence to deal with the horrendous problems of devastated Germany. He declined the offer and recommended General Lucius Clay, a brilliant organizer who had been in charge of keeping supplies flowing to the armies in Europe. On March 31 Clay was appointed Deputy Military Governor under Eisenhower. McCloy was sent over to present this surprise assignment to the Supreme Commander, who had not been consulted. After some soothing, Eisenhower agreed that, as in Italy, a Military Government was the most suitable solution, at least for the early stages of occupation.

After Yalta the Departments of State, War, and Treasury had combined to produce a detailed policy directive for the Military Government commander. Negotiations and maneuvers of Byzantine complexity followed. The result of these efforts was the infamous document known as JCS 1067, in which Morgenthau’s ideas were considerably softened and many loopholes were left for improvisation, but which still retained a punitive approach. Germany, it declared, “will not be occupied for the purpose of liberation, but as a defeated enemy nation.” The occupiers were urged to be just, but firm and aloof, and fraternization with German officials and population was forbidden. Living conditions were to be kept below those of the Allied nations. Reparations programs were to be enforced, and the economy “decentralized.” Works of art, classified as one type of property

in the financial section of the directive, were to be “impounded regardless of the ownership thereof.” There was little useful detail in this document, which noted only that “all reasonable efforts should be taken to preserve historical archives, museums, libraries and works of art.”

84

Moreover, because of their “top secret” classification even these deceptively simple instructions could be revealed only to a very few high-ranking officers. The plan’s vague and negative requirements would, if taken literally, make the governing of Germany essentially impossible. The Army, stuck with a job it never wanted, would be forced to improvise as situations presented themselves. Clay read this document for the first time in early April 1945, as he flew to Paris to take up his duties. The surrender of Germany was a month away.

During all these highly secret machinations the Roberts Commission representatives, in consultation with Hammond and Hathaway at SHAEF, continued to work on the formulation of a restitution policy with representatives of the Allied and occupied nations. Their requests for guidance, sent to the State Department, were virtually ignored (not surprising given the battles over occupation policy which were in progress). In London the Allied nations had produced a number of ideas, having finally agreed on such basics as the precise definition of a work of art, and what exactly was meant in legal documents by the French word

spolié

, or “looted.”

85

These weighty matters having been resolved, there was general agreement that all property “taken to Germany during the occupation would be presumed to have been transferred under duress and accordingly treated as looted property.”

It was also agreed that identifiable works should be returned to the governments of the countries from which they had been taken, and not to individual owners. A United States Military Government law ordered a freeze on all trade and the importation or exportation of works of art from Germany. And again it was proposed that Germany should be obligated to replace lost works with comparable objects from its own collections. To carry out this process, referred to as “restitution in kind,” some sort of international commission was envisioned which would adjudicate claims. These ideas were sent for approval to the State Department by the Roberts Commission in July and November 1944, and again in February 1945.

86

The Allied governments avoided commitment on this subject, as they had on everything else. The State Department finally informed the RC that all restitution matters would have to be referred to a Reparations Commission which the Big Three had ordered to be established at the Yalta Conference. The only trouble was that as of April 1945 no Reparations Commission had yet been appointed.

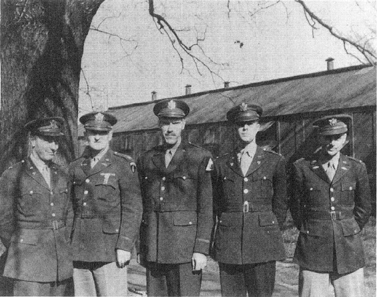

Monuments men (left

to right)

Mason Hammond, Henry Newton, John Nicholas Brown, Calvin Hathaway, and Kenneth Lippman

John Nicholas Brown, whom the RC expected to advise Eisenhower on these matters, had arrived in London on March 9, 1945. He found a “blind town,” whose blank, boarded-up windows offered only slight protection against Hitler’s ultimate weapon: the V2. Indeed, shortly after his arrival he was slightly wounded by flying glass during an attack. All the iron railings in the parks had long since been melted down. Dressed in the uniforms of many nations, the inhabitants groped their way around the dimmed-out streets. But the knowledge of imminent victory gave a feeling of hope and there were jonquils in the fenceless parks and plenty of theater, the new Olivier film of

Henry V

, some heat and hot water, and amazingly good food still served with style at the Connaught and other watering spots. Hammond, Hathaway, and Crosby took Brown around London and taught him all the tricks of wartime living and transportation. They introduced him to various generals “who greeted me warmly and told me they wanted a long talk soon,” he wrote to his wife.

To Brown’s surprise, Newton, about whom he had been briefed in

Washington, now appeared to be the acting head of a new division called Reparations, Deliveries and Restitution, to which Brown seemed to be assigned. After five days it was painfully clear that “General Hilldring and David [Finley] had given me a complete misconception. There was no question of heading up a brand new project, choosing personnel, etc. It was all chosen and going and more or less cut and dried, at least in this planning phase. Thus there was no great grandeur. I had no aide, no great field of usefulness, and as for Gen. Ike, well he was just titular head way out yonder. To say I am aide to Gen. Ike is really ludicrous.”

87

Brown thought Newton (whom he described as a “California church architect”) and the others were doing a fine job; he was so impressed by Newton’s ability to circumvent Army red tape that he recommended that efforts continue to put him in charge of “all our MFAA officers.” MFAA, he confided privately, “ranks in the Army

very

low.” Brown took all this in good humor, but he was not without resources. When McCloy came to London, Brown “got to see him, to the amazement of the Army.” McCloy told him to talk to “Major Gen. Clay, the new head of the Control Council.” This proved not to be so easy, as Clay was in Paris. Brown, not as brazen as Francis Henry Taylor when it came to unauthorized travel, settled down in London and quietly immersed himself in his new subject, hoping to be useful in the diplomatic end of things presently being handled by Sumner Crosby, and eventually at SHAEF headquarters when he should be called there. Sir Leonard Woolley he found “agreeable and not difficult.” But after suffering through a dinner seated next to Lady W., the other half of the team, he could only comment that she was “a combination of tactlessness and snobbery.”

Brown had no trouble working with both Woolley and Newton on restitution policy. (Finley was thrilled with this rare report of harmony at headquarters.) By early April further principles of restitution were taking shape in London. Ecclesiastical property from German churches, they all strongly felt, should be exempted from use for replacement in kind. The British, Brown reported back to Washington, were against using any works of art, including German-owned ones, for reparations, and he suggested that the United States announce a similar policy which would stipulate that “cultural objects in German public or private collections may not be included in an estimate of German capital assets to be seized or held for the purpose of ultimate reparations.”

88

This principle he considered “vitally necessary,” and he suggested that the Treasury Department be consulted on the matter.

A few days after making these recommendations Brown was finally moved across to France and the little town of Barbizon. Newton thought it

a good time to take him on an inspection trip to Italy, and arranged yet another Papal Audience and a tour through the newly liberated north, where they were briefed on the discovery of the repositories at San Leonardo. This junket, organized in considerable style by Newton, was perhaps the final straw for his Army enemies, who angrily cabled that he was in Italy “without prior clearance” and was signing communications “Special Advisor, War Department.” Brown’s status was even less clear. “Requested is extent to which he may be considered to represent War Department views,” one officer inquired. Hilldring at Civil Affairs replied unhelpfully to these cables from Italy that “the War Department has no knowledge as to how Newton and Brown got to your theater or why they are there,” but said that “it would be appreciated if you will listen to Mr. Brown’s views. Of course you are at liberty to do what you please regarding his recommendations.”

89

Little did Brown know how very “low” the MFAA mission did rank in the eyes of the Army brass.

XI

ASHES AND DARKNESS

Treasure Hunts in the Ruined Reich, 1945

In the first months of 1945 the small group of Monuments men in the forward echelons moved into the thin strip of newly conquered German territory immediately behind the front lines. It was shockingly different from what they had encountered thus far. The previous October, Aachen had given them a glimpse of the destructiveness of total war, but the constant saturation bombing and fierce resistance of the German armies since that time had further reduced the “skeleton” cities to flat wastelands of rocky rubble sometimes relieved by pockmarked cathedrals, spared thanks to the maps provided by the Roberts Commission.

The remaining inhabitants of these moonscapes lived marginally in cellars, while newly liberated groups of half-starved forced laborers and displaced persons roamed about looking for food and anything of value that might be exchanged for it. In such conditions the protection and repair of historic buildings was, for the most part, a ludicrous impossibility. Nevertheless, the MFAA officers continued to do what they could to salvage chance finds of sculpture or movable works from the smoldering heaps of stone and gather them in more protected places which could be put under guard. It was discouraging and dangerous work: on March 10 British Major Ronald Balfour was killed by artillery-shell fragments while trying to save sculptures from a fourteenth-century church in Cleve.

To George Stout, waiting impatiently for the liberation of the constantly growing list of repositories which Intelligence sources were reporting, this tragic event made the magnitude of the task set for the tiny number of MFAA officers more ominous than ever. There were now only five of them in the forward area. At fleeting meetings with the policy makers at headquarters, or by telephone, Stout tried to organize the forward placement of his colleagues and prepare procedures for dealing with the large deposits of works of art which he knew they would soon encounter. He circulated a list of German museum personnel who might reveal the locations of their repositories and thereby prevent their destruction. At the top was Count

Metternich, who had returned to his post as Provincial Curator in Westphalia after being fired by Goering. But he was not to be found in Bonn when it was taken. Nor were there any museum officials in Cologne to tell Stout where their holdings had been hidden. It was not a place in which he wanted to linger. To his wife he wrote that he felt “bitterness, hatred—the way you feel a raw north gale.”

1

This was hardly surprising, considering the fact that heavy bombing of the cities to the east was still going on, and that the German radio continually broadcast bulletins such as the following:

Other books

The Best Laid Plans by Terry Fallis

The Irish Warrior by Kris Kennedy

Zepha the Monster Squid by Adam Blade

Forbidden by Cheryl Douglas

The One For Me by Layla James

Raising A Soul Surfer by Cheri Hamilton, Rick Bundschuh

Blush (Rockstar #2) by Anne Mercier

LONDON ALERT by Christopher Bartlett

DEBT by Jessica Gadziala

The Cloud Pavilion by Laura Joh Rowland