The Rape of Europa (65 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

Art professionals looked at the collection from a different perspective. National Gallery chief curator Walker, who inspected it on July 21, wrote that Goering “was obviously swindled during the years he was buying pictures,

but he had excellent advice when it was a matter of looting. Superb paintings from the Rothschild, Koenigs, Goudstikker, Paul Rosenberg, Wildenstein and other private collections and dealers. His famous Vermeer is a fake which must have been painted four years ago for him.”

22

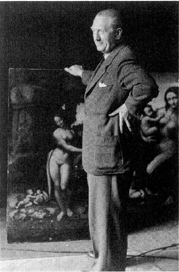

Walter Andreas Hofer meets the press at Berchtesgaden.

Hofer’s performance was topped by that of his former boss, who in the first days of his incarceration sent his valet, with an American escort, to see Frau Emmy and bring some clean laundry and, to while away the prison hours, an accordion. He also told his man to bring him the tiny Memling

Madonna

from the Rothschild collection, which was part of his wife’s “nest egg.” Piously stating that it did not belong to him, but was “from the Louvre,” he presented it to one of his American jailers. The valet later testified that Goering had told him that the intended recipient was “a German-born naturalized American citizen who had migrated to America in 1928 and that he was the son of a Prussian Security Police master musician.” The issue of this rather unusually talented father spoke German fluently with a Berlin accent, and “Goering frequently visited this officer’s billet, usually returning from these visits in the early morning hours and in a fairly intoxicated state.” The Reichsmarschall had sadly misjudged the appeal both of the old country and bribery to his now thoroughly American captor. The painting, with a certain amount of fuss, was returned to the 101st Airborne, and Frau Emmy was relieved of her remaining insurance pictures.

23

In all these goings-on before the collection could be completely secured, two of the four little Memling

Angels

from the Goudstikker collection, which had also been taken from Frau Emmy and put with the rest, a Cranach, and two small van Goyen landscapes disappeared, as did a tiny painting of Madame de Pompadour attributed to Boucher. An American officer had found it lying somewhere in Berchtesgaden. On his next furlough

he took it to Paris and presented it, in a paper bag, to a lady friend serving in an American agency. She liked it, but thought nothing of it, and eventually brought it home. A few years later she married someone else, and hung it in a corner. It was not until much later that someone remarked that it looked like a good painting. Investigation revealed not only the attribution but that it had been confiscated from a branch of the French Rothschilds, who had long since collected their insurance and did not wish to revive old problems. The chance owners still have it, now rather more prominently displayed, in their drawing room.

After the first excitement, the tedious work of inventorying began. Lists had to be made of what was in American hands, and compared to other lists gleaned from interrogations and Goering’s records. Only then would the officers know what was missing. An appeal to the good burghers of Berchtesgaden to turn in “found objects” did not get much response. Later their depredations would be more carefully investigated, but for now the MFAA had more than enough to handle: on May 8 Third Army had reached Alt Aussee, which by its sheer magnitude would eclipse every other find.

The arrival of the American presence had not been very dramatic. Commanded by Major Ralph Pearson, two jeeps and a truck full of soldiers of the Eightieth U.S. Infantry crept carefully up the steep roads to the mine head to check on the reputed repository. They were especially alert because they were entering the heart of the “Alpine Redoubt,” which was supposed to be the last bastion of the fanatic core of the Nazi establishment, and they were not sure if word of Germany’s surrender had reached this remote region, or that it would be honored even if it had. Not only was there no resistance: the machine-gun-toting guards sent by Eigruber surrendered like lambs, and Major Pearson was soon overwhelmed by helpful mine and cultural officials who fell all over themselves in their desire to claim credit for having saved the works of art.

24

The Americans were shown the famous bombs, and a folksy group photograph of mine workers, GIs, and art guardians was duly taken. (This image, which was widely distributed, identified the whole group as “Austrian Resistance Movement miners.”) For the time being the Americans remained unaware of the exact roles of the Alt-Aussee personnel; they were more concerned with establishing order in the town and protecting the vast mine.

Posey and Kirstein, called to inspect, were delayed at the foot of the steep road up to Alt Aussee for hours by still fully armed but cheerful elements of the German Sixth Army and their camp followers, who were descending to the prisoner-of-war cages near Salzburg to surrender. Once at the minehead, it did not take architect Posey long to open an access

through the blocks in the main shaft. In the second room they entered, “resting a foot off the ground, upon four empty cardboard boxes, quite unwrapped, were eight panels of

The Adoration of the Lamb.”

They had found the Ghent altarpiece. To Kirstein “the miraculous jewels of the Crowned Virgin seemed to attract the light from our flickering acetylene lamps.” Farther on was the Bruges

Madonna

, still on her sordid old mattress, covered with a sheet of asphalt paper.

25

The Ghent altarpiece at Alt Aussee

The ancient, labyrinthine mine, in which chambers could be approached from various levels and directions, was extremely difficult to secure. Moreover, it was impossible to tell who could be trusted, as the stories of those involved in Alt Aussee’s operations were equally labyrinthine. Kirstein wrote that “factions among the mine personnel were at each other’s throats, each claiming the credit for having uniquely, and against the others, saved the mine.”

26

Scholz of the ERR, who had made good his promise to send armed men to the mine (immediately arrested by the Americans), sent Posey a long report which, he pompously wrote, “supplements in detail the information that I had already given to Dr. Lincoln Kirstein” and was “a true account of the part played by the Special Staff, Fine Arts [ERR] in the measures taken for the prevention of this act of terror.”

27

Posey, unimpressed, had the most obvious Nazis arrested and set the

rest to work. But George Stout was repelled, and wrote: “I am sick of all schemers, of all the vain crawling toads who now try to edge into positions of advantage and look for selfish gain or selfish glory from all this suffering.”

28

The task before them would eclipse these emotions.

On his first visit to Alt Aussee, Stout, using available records, estimated the contents as follows: “6,577 paintings, 2,300 drawings and watercolors, 954 prints, 137 pieces of sculpture, 129 pieces of arms and armor, 122 tapestries, 78 pieces of furniture, 79 baskets objects, 484 cases thought to be archives, 181 cases books, 1,200—1,700 cases apparently books or similar, 283 cases contents completely unknown.”

29

This did not include the Vienna holdings at Lauffen. Stout went back to Third Army headquarters to report on his findings. He felt the things in Alt Aussee would be safe, from the conservators’ point of view, for years, and that careful plans for the safe removal and storage of the objects should be prepared. He calculated that it would take at least six weeks to “get out the bulk of the important holdings.”

30

On the day Stout had gone up to Alt Aussee, Calvin Hathaway, busily planning his next foray at Seventh Army headquarters in Augsburg, received an intriguing call from the German Army’s liaison office at Zell am See, not far from the big mine. The German Supreme Command, he was told, “is in possession of valuable works of art which it wishes to transfer to the custody of the civil administration at Innsbruck.” The caller did not say where or what the works were. Hathaway dropped everything and went to Zell am See, where he learned with some effort that the works were the hijacked pictures from the Vienna Kunsthistorisches and that they were now in Sankt Johann in the Tirol. At the American Forty-second Division Intelligence office in Kitzbühel, where he next proceeded in order to make arrangements to retrieve what was essentially the cream of the Vienna collection, he was forced to endure a little “lecture on the triviality and unimportance of works of art” from the commanding officer, who nonetheless did provide the required help.

In the little ski town of Sankt Johann, Hathaway’s party was directed to the Golden Lion Inn, where “the preliminary reluctance of female owner and English speaking niece to admit any knowledge of works of art on premises was brought to nought by Emil God, guest of the house.” God (no relation) took them next door to his house and down to a damp basement with puddles on the floor, where they found thirty-two uncrated pictures, forty-nine sacks of tapestries, and nine opened wooden packing cases. God claimed that the Germans who had left the cases there had said they contained food, and that he himself had opened them to get some. The pictures had not been unpacked. Interrogations in the little town produced

numerous versions of the arrival of the objects and of their concealment. God said SS officers had threatened him and tried to take some of the works. He whispered to Hathaway that he was sure Cellini’s famous

Salt Cellar

, the only known work from the master’s hand, was in one of the boxes, which does not seem to have been the case. Hathaway recommended that God be questioned further if it did not turn up. The mayor said he had not told the constantly changing American units about the cases because he “felt no confidence in American interest” and feared the objects would end up in Germany.

The Forty-second Division, noticeably more enthusiastic when apprised of the value of the little cache, now agreed to post guards and move the pictures upstairs to God’s sitting room. There was the usual scramble for protective blankets and packing materials, during which the CO fiercely offered to take the former “from the beds of the Nazis of the town,” which proved unnecessary when a quantity was found in a German military hospital. The pictures were taken to safe storage in the Mozarteum in Salzburg.

31

It later appeared that little Sankt Johann had been pretty busy in the last days of war: in a barn belonging to the Chief Forester, CIC agents found $2 million worth of various foreign currencies, and several sacks of gold bars, jewelry, and coins, which were to have taken care of SS chief Himmler in future years.

32

There were other hard-core Nazis who had made careful preparations for the future. No one had been harder-core than Mayor Liebl of Nuremberg, who had so assiduously procured and protected the greatest Germanic treasures for his city. The elaborate bunkers built under the eleventh-century Kaiserburg, which extended underground well out under the streets, were a marvel of construction and climate control. In them he had put the Veit Stoss altarpiece and the Holy Roman regalia, along with Nuremberg’s more legitimate collections. One access to the bunker was through a secret entrance disguised to look like a plain little shop on a small side street. From there a long concrete ramp, blocked at intervals by ten-foot-high steel doors, led to the foundations of the castle.

Despite his faith in the Führer, the thin wedge of doubt had eventually penetrated even the mayor’s mind. After heavy air raids in October 1944, Liebl, having consulted Himmler, ordered special copper containers to be made for five pieces of the Holy Roman regalia: the crown, Imperial sword, sceptre, Imperial globe, and the sword of St. Maurice. The pieces were unpacked from their original cases and put in the new ones, which were soldered shut. The boxes were then, in greatest secrecy, walled up by Liebl and two city officials, Drs. Friese and Lincke, in one of the passages in the bunker complex on March 31, 1944. Liebl and the top SS leadership

then concocted a cover story to the effect that the regalia had been taken off by the SS and sunk in Lake Zell in Austria. To make the story convincing, a removal was actually staged with the help of two local SS men. Alas, Liebl, his faith shattered, burned his papers and committed suicide on April 19, as Allied troops poured into his Germanic city. The intact bunkers, to which cooperative city officials provided keys, were discovered and put under guard.

Other books

The Secret of Willow Lane by Virginia Rose Richter

The Last Summer of the Camperdowns by Kelly, Elizabeth

The Seventh Secret by Irving Wallace

The Belial Stone (The Belial Series) by Brady, R.D.

Strontium-90 by Vaughn Heppner

Inexperienced Mage (Reawakening Saga) by Jackson, D.W.

Never Forgotten (Never Forgotten Series) by Risser, Kelly

A Plague of Sinners by Paul Lawrence

Million-Dollar Amnesia Scandal by Rachel Bailey

This Way to Heaven by Barbara Cartland