The Rape of Europa (58 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

At Martin Fabiani’s gallery Rothenstein greatly admired an edition of the works of Buffon illustrated by Picasso which the dealer had published. Alas, it had long since been sold out, but Fabiani generously promised to find Rothenstein a copy.

58

Not long after this visit opportunist Fabiani, making a quick shift, put on a show to benefit British war wounded, which featured a number of high-grade works lent by M. de Galea, a fancy catalogue by Louis Aragon, and,

piece de résistance

, a painting by Winston Churchill.

59

Liberators in the know, beginning with Hemingway, who left a box of live grenades at Picasso’s studio, sought out their icons and found them safe. Picasso was mobbed. Kenneth Clark wrote that his studio was “stratified. … On the ground floor there were GI.s and American journalists; then came communist deputies and prominent party members who showed signs of impatience; then came old acquaintances; and finally one came to Picasso.”

60

Others went to Gertrude Stein’s fabled apartment. She was not yet there, though she had indeed been liberated by the Allied armies coming up from Marseilles. She, Miss Toklas, and their dog, Basket, did not return to Paris until December, again with the portrait by Picasso in the car, which served as a passport when they were stopped by armed Resistance members. Only a few things were missing from the apartment, taken at the last minute by roving SS troopers who had intended to destroy the “degenerate” Picassos there but, clearly no longer the supermen they once were, had been chased off by gendarmes called by the neighbors.

61

Despite the meagerness of their collections the museums soon reopened. The Carnavalet was first again with a show in September. The Louvre put

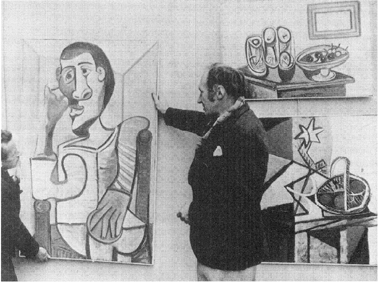

on a special exhibition of the Bayeux tapestry with the part showing the defeat of the British tactfully folded behind more palatable scenes. The galleries containing its unevacuated sculptures were opened too, but just in case the bombs came again, all the statues were carefully placed with their backs to the windows. The most precious things could not yet come home, for there was no coal to heat the vast museum spaces. But there was a Salon d’Automne at the Tokyo, and here Tate director Rothenstein finally saw convincing evidence of the rigors of the occupation in the “lassitude and frustration” expressed in many works. To him it even showed in many of the paintings by Picasso, who had been specially honored by a sort of retrospective of seventy-four pictures within the Salon. Picasso’s extreme modernism, plus his controversial and much-publicized membership in the Communist party, aroused so many from this lassitude that there were riots in the galleries, during which his canvases were ripped from the walls. Twenty gendarmes had to be posted in the rooms for the duration of the show. When Rothenstein described the changing of the guard in the galleries, Picasso was delighted and said, “Just like Buckingham Palace, isn’t it?”

62

Hanging Picassos for the Salon d’Automne, 1944

In their peregrinations around the châteaux in the countryside and the houses, palaces, and museums of Paris, the Monuments men had also been collecting information on the millions of things which had disappeared, presumably to the Reich. It was nearly impossible to be precise. Objects hidden or misplaced by collectors, Jewish and otherwise, appeared unexpectedly in closets, armoires, and barns, near and far from their proper locations. Boiseries from one château were found a few miles off in a neighboring one. Some things had not been hidden or stolen at all. Guy de Rothschild found a missing Boudin in his stables. In Robert de Rothschild’s Paris house, inhabited by a German general throughout the war, all was impeccably in place.

The owners themselves, who had left objects in the hands of retainers, friends, lawyers, and bankers, often had no idea where to start looking. Some things were entirely forgotten. Although German troops had been billeted in the château of the jeweler Henri Vever and had taken a collection of gold coins, they had not found his magnificent Islamic miniatures, though it was assumed that they had. Vever died peacefully during the occupation, and the miniatures, left to his family, were packed away and would not reappear until 1988. Inventories, if they existed at all, could be maddeningly vague. One officer wrote, “It is still not possible to ascertain what was hidden by … collectors before and during the German occupation, what the Germans destroyed in contradistinction to what they carried away … what was moved from one house to another by the Germans and what has just been mislaid during a period of disorder.”

63

Little was as yet known of the details of the art trade and the operations of the ERR, and for a very long time the single best source on this subject, Rose Valland, trusting no one, kept her carefully collected data to herself, though she did hint at her knowledge. After a time no one was certain if she really knew anything or not. She did know enough about bureaucracy to be sure that if she turned over her precious lists and photographs to SHAEF they might disappear without trace.

In her dealings with James Rorimer over the installation of the post office at the Jeu de Paume she felt she had found an American who did not “give the unfortunate impression of having arrived in a nation whose inhabitants were not important.” Rorimer was first impressed by the accuracy of her knowledge when they went together to inspect the famous train liberated by Alexandre Rosenberg, but it was not until December that Mlle Valland finally agreed to take him to the former haunts of the ERR. The tour began with a garage at 104, rue Richelieu, where they found thousands of confiscated books divided according to subject and destination and stacked up, ready for shipment to Germany. They went on to Lohse’s

apartment and various ERR offices where Rorimer picked up numbers of German documents which gave the MFAA men their first detailed insights into Nazi confiscation activity.

In his diary Rorimer noted that Mlle Valland, though recently appointed Secretary of a newly created French committee for recuperation of art, “has not yet given the French authorities all of her information about the destination and location of works of art sent to Germany.” This, according to a later book by Rorimer, she confided to him alone over a candlelit supper, with champagne,

chez elle.

Mlle Valland’s own book omits the romantic details, but her trust in Rorimer is clear, and she duly presented her lists both to her French colleagues and to the MFAA officer, whom she urged to go to Germany as soon as possible to make sure that the Allied vanguards would be aware of the ERR repositories. But Rorimer could do no more than send this information on to the forward echelons. He himself would not be sent to Germany until March 1945, by which time a number of things were no longer where Mlle Valland thought they were.

There had, of course, been plenty of preparing in Germany for the inevitable Allied incursion onto the Continent in the north. The storage places stuffed with confiscated works which awaited the Reich’s victory in order to be displayed not only would never be emptied into Hitler’s museums and government palaces; they were now in considerable danger from the aggressive bombing tactics of their former owners.

The Berlin museums, like everyone else, had begun preparations to shelter their own collections from air attack in the thirties.

64

During the Sudeten Crisis things were put in basements and a few very important ones in the vaults of the Reichsbank, but they were ordered back on display by the Nazi government so as to calm public opinion. Somewhat resentful, the curators intensified their in-house preparations. Rumors of the coming invasion of Poland reached them on August 25, 1939. By this hour the French and British collections were already on the road. Nothing in Berlin had been moved, nor were there instructions from the Nazi government. This time the Prussian Minister of Finance told the director of the Antiquities Division, Carl Weickert, to take charge of finding shelter for the Berlin collections and not worry about intervention. For the time being, though the collections were packed, they stayed in the city, stacked in fortified basements or in the vaults of the Mint and the Reichsbank. A protective structure was placed around the virtually immovable Pergamon altar.

Other jurisdictions, less confident than Berlin of their cellars and defenses, had begun to send things to the country. Soon there was hardly

a schloss in the Reich without stored treasures. The Vienna museums had established 108 repositories in Austria. Dresden occupied 60. The Rhineland museums, closest to an enemy after the fall of Poland, sent a great deal to the east of Germany, while the Bavarian collections were scattered south of Munich.

A bombing raid on Berlin in December 1940, which blew away the Pergamon frieze protection like so much cardboard, led to reconsideration of matters. In early 1941 the altar was dismantled with great effort—it was necessary to take down the outer wall of the museum—and, each piece having been carefully marked, was moved to the Mint, which itself was reinforced with several layers of concrete. The fabulous Trojan gold treasure, thought to have been owned by King Priam of

Iliad

fame, was moved in three chests from the Prehistory Division to a vault at the Prussian State Bank.

As the bombing increased it was soon clear that even this might not be adequate. Still, no one considered moving things out of town, but discussed using space in the huge antiaircraft towers, surmounted by guns, which were being built by Speer and were said to be able to withstand any known assault. Although many of the museum directors disliked the idea of being under military control, it was decided to place the best Berlin objects in these towers. Between September 1941 and September 1942 this operation was slowly accomplished. There were two towers: the one at Friedrichshain held the cream of the Kaiser Friedrich Museum, or Gemäldegalerie, much of the print collections, the Islamic holdings, and the famous bust of Nefertiti; the other, near the Zoo, sheltered, among other things, the paintings of the purged Nationalgalerie, and the Trojan gold.

In the year it had taken to accomplish this storage the military situation had totally changed. The war in Russia was not progressing as expected and bombing increased steadily. The previously unthinkable idea of fighting within Germany had crept into everyone’s mind, and although no one yet envisioned Berlin as a battlefield, evacuation of the collections from the city was once again discussed. But it was not until March 1943 that Weickert, reinforced by a directive from the Propaganda Ministry to find absolutely secure storage for all collections, was able to persuade his colleagues to consider sending them to the deep mines dotted around Thuringia, and nothing was actually moved until June 1944. The first items went to a mine at Grasleben, about thirty-five miles west of Magdeburg, on the busy day of June 6. Despite the news of the Normandy landings and the new horror of incendiary bombs, only the second-class items still left in the museum cellars were sent.

In January 1945 the Wehrmacht suddenly ordered the museums to clear out of part of the Zoo tower. In the few hours a day in which there was no bombing, the precious objects were transferred to the Friedrichshain tower. But the Russians were now so close that it was all too clear that even this would not be safe. The terrible fire bombing of Dresden which began on February 13 intensified all fears. There were rumors that everyone would be evacuated from Berlin. Museums director Kümmel begged his Ministry for permission to move things to the West. The Ministry agreed, but even at this juncture some division directors, balking at the idea of moving things on the dangerous roads, withheld approval. Exasperated, Culture Minister Rust asked Hitler for a decision. The Führer, whose own collections, as we shall see, had long since been taken to safety, and who was by now aware of Allied plans made at Yalta for the partition of Germany, finally gave the order for evacuation on March 8, 1945.

Other books

Hot Shot by Kevin Allman

Stuff to Die For by Don Bruns

Woman with a Blue Pencil by Gordon McAlpine

If I Stay by Gayle Forman

The House at Sandalwood by Virginia Coffman

Firehurler (Twinborn Trilogy) by Morin, J.S.

Rebel by Francine Pascal

Excess Baggage by Judy Astley

Fourmile by Watt Key