The Rape of Europa (71 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

Repeated attempts by Berlin officials to gain access to the Collecting

Point were resisted by both Otto and the British. It was not until September 1947 that a new assistant, using inventory lists recently sent from Berlin, discovered that thirty-two pieces of the gold hoard were missing. By now it was impossible to tell at what point they had been removed. Otto and his staff were all fired by the embarrassed British, and a police investigation instituted. A curator from the Schloss Museum in Berlin was put in charge of the Collecting Point. Further inventorying revealed that more gold items had vanished. They have never been found.

13

British officers faced with hundreds of uncrated Nationalgalerie pictures at Grasleben

While the field officers were engaged in these strenuous activities, certain of their peacetime colleagues were collecting people and information. The OSS Art Looting Investigation Unit, consisting of naval officers/art historians James Plaut, Theodore Rousseau, and Lane Faison had begun operations in Germany in late May 1945, in a gingerbread-covered villa conveniently located not far from Alt Aussee. Their information was not only of interest to the MFAA officers; their principal sponsorship was by the Army Judge Advocate’s office, which was investigating war crimes. Before they arrived in Germany the three officers had already looked into Alois Miedl’s activities in Spain and attempted without success to extradite him. They had done further preliminary work in France and England, drawing on the documents collected by the Intelligence agencies of various

nations. Since the previous autumn Army authorities had had lists of the Nazi art principals, and Douglas Cooper of British Intelligence had been questioning any POWs taken to England who seemed to have art backgrounds. Lists of suggested questions and names of Nazi agencies were distributed to all Intelligence units. By the time the Alt Aussee interrogation center was set up, Mühlmann, Lohse, Hofer, Goering’s secretary Gisela Limberger, and all of the Reichsmarschall’s records were in custody.

The work of arrest and interrogation was not so pleasant: Frau Dietrich dropped all the charm she had displayed to the Führer when Lane Faison came for her account books, but soon calmed down when she saw the pistol (never used) he wore.

14

Once in captivity, the German art purveyors spoke volumes. Hofer seemed able to remember every transaction, reeling off the details of certain of them with ease while avoiding those which revealed his own venality. Mühlmann, after trying to escape twice and responding initially with contempt, eventually talked a great deal, even telling his captors little anecdotes about Hitler and Hoffmann. His testimony is full of claims: that he tried to keep collections together, that he tried to save things for Austria, that he helped preserve Polish treasures. But unlike many of his colleagues, he had no illusions about the reality of his acts and at the end of one statement wrote, “The Third Reich had to lose the war because this war was based on robbery and on a system of injustice and violence, which could only be broken from the outside. Every individual has now to pay personally for the mortgage which the German people has accepted.”

15

Some had paid already. Bunjes was not the only suicide: von Behr was found, still in his uniform, together with his wife in his apartments at Schloss Banz near Bamberg. They had gone out in style by drinking an excellent vintage (1918) champagne laced with cyanide. In a storeroom deep in his cellars, walled up for an unknown posterity, were all the records of Alfred Rosenberg’s ill-fated Ministry, which now would be used as evidence at Nuremberg. Haberstock and his records were found nearby at the castle of the Baron von Pollnitz, who had been so helpful in the retrieval of the Wildenstein collection from its Louvre guardians. Gurlitt was there too. After Haberstock was arrested, von Pollnitz told Frau Haberstock that he would hide the dealer’s remaining pictures if she would reveal their whereabouts. She declined this offer. MFAA officers later by chance found some of them in the famous Schloss Thurn and Taxis in Württemberg.

Hermann Voss was different. He managed to travel to Wiesbaden, where he offered to assist the Americans in the recovery of the Linz collections

from Alt Aussee. It seems never to have occurred to him that his wartime activities would be viewed as criminal by the Allies; he expected that the Americans would arrange for his wife and his personal papers to be brought from Dresden so that he could donate them to some public institution or university, where he no doubt planned to continue his studies. He even presented the Monuments men with a copy of his poem deploring the German conquest of France. He was, therefore, quite amazed to be arrested immediately by Walter Farmer and sent off to Alt Aussee to be interrogated.

16

It took longer to track down ERR executive Gerhard Utikal, who knew all too well what was in store for him and had started working on a farm under an assumed name. His wife and two small children were found in a small Bavarian town. When “confronted with the alternative of either revealing her husband’s whereabouts or of being interned herself,” she yielded his address. The officer who had located Frau Utikal was later congratulated by MFAA officer Thomas Howe for the “discretion and psychological skill used in dealing with [her].”

17

As the Nazi art gatherers and their records were brought in, the OSS trio slowly began to comprehend the staggering magnitude of the German operation. The more they learned, the less sympathy they had for those who had traded with and for the Nazis. And indeed the evidence of cynical collaboration was devastating. Reports and questioning produced endless examples of betrayal and corruption, and of the extraordinary ability of the Germans to compartmentalize and rationalize their actions. Their responses for the most part have a terrible similarity: they were only protecting the art; they were only following orders. These statements were backed by reams of stamped and notarized testimonials from wives, doctors, and colleagues who always mentioned that those being questioned helped this or that Jew, and only gave lip service to the Nazi party.

After the months of investigation Plaut, Rousseau, and Faison produced three very long and overwhelmingly detailed “Consolidated Interrogation Reports.” Another on the Dienststelle Mühlmann was written by Jan Vlug, a Dutch Intelligence officer working with them. Separate reports were also filed on each of the principals. Again and again the feelings of the writers penetrate their official prose. In the middle of his endless pages of details Vlug allows himself to exclaim that Mühlmann is “obstinate, he has no conscience, he does not care about Art, he is a

liar

and a

vile

person.” Rousseau felt that his analysis of the Goering collection “dispels any illusion that might remain about Goering as the ‘best’ of the Nazis. In this one pursuit in which he might have shown himself to be in fact a different type of man, he was the prototype of all the worst in National Socialism. He

was cruel, grasping, deceitful and hypocritical… well-suited to take his place with Hitler, Himmler, Goebbels and the rest.”

18

Faison recommended that the Linz operation be declared a criminal organization. Nazi looting, he wrote, was different from that of any previous war in having been “officially planned and expertly carried out… to enhance the cultural prestige of the Master Race.”

19

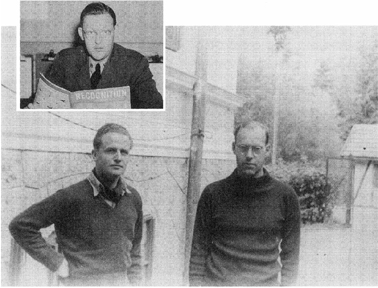

The OSS team: Theodore Rousseau

(left)

and James Plaut at their interrogation center (Inset: Lane Faison, July 1945)

Despite their disgust the OSS and MFAA men were human. Craig Smyth, who later had to supervise the house arrest of Hermann Voss, found it difficult to treat so eminent a scholar as a criminal and had him report daily to someone else. Monuments officer Charles Parkhurst, sent to question the widow of Hans Posse, whom he found living on the proceeds of sales of the pathetic contents of two suitcases of family bibelots, described her as a “gentle, elderly person” and broke off his interrogation when she began to weep. In the few answers she did provide it was clear that she was very proud of her husband’s accomplishments. She even showed Parkhurst photographs of Hitler at Posse’s state funeral, but of his actual transactions she clearly knew nothing.

20

Plaut doubted that Bruno

Lohse had really known the extent of Goering’s evildoing and noted that both he and Fräulein Limberger had become despondent when all was revealed. Rousseau and Faison too, after weeks of questioning Miss Limberger, were convinced that despite the fact that she had read the damning daily correspondence from Hofer to Goering, she bore no blame. When they had finished with her, Faison could not bring himself to leave her at the squalid internment camp to which she had been assigned and instead asked her where she would like to go. She named the Munich dealer Walter Bornheim, he of the suitcases full of francs, and a principal supplier to both Linz and Goering. Faison consented, and left her at the military post in Gräfelfing, where Bornheim lived.

21

In June 1945 both the Americans and the Europeans, who by now had established their own recovery commissions at home, still believed that an international restitution commission would be set up. The day the Reparations Conference opened in Moscow, in a breakthrough for the British, the European Advisory Council back in London agreed that German works of art should not be used for reparations “pending restitution.”

22

After this had been completed, according to their thinking, claims would be made to the still dreamt-of international commission for the “replacement in kind” of missing or destroyed items, an idea particularly dear to the French. None of this could take place until the structure of the four-way occupation of Germany had been agreed upon by the Big Three at their summit conference which would begin on July 17 in Potsdam, just outside Berlin.

By the second week of July, SHAEF headquarters in Frankfurt swarmed with officers and diplomats preparing for the coming conference. John Brown had arrived on June 12, after a tour of the American-held repositories, and was billeted in a comfortable, fully furnished “middle-class” house lacking only hot water. These amenities, he discovered upon reading his billeting notice, had been guaranteed in the following manner: “Occupants will not be notified prior to four hours before they must complete evacuation, so that the houses will be left habitable. Occupants will not be permitted to remove furniture, rugs or furnishings.”

23

John Walker had joined him there, living on the princely per diem of $7.00 per day, to prepare for his inspection trip. Brown, who had finally met with Clay to discuss MFAA thinking, was optimistic that “something really constructive will eventuate from this meeting at Potsdam. … I sense a feeling in the air…. President Truman is a great man in his quiet way.”

24

MFAA discussions concentrated on the future inter-Allied restitution commission and its relation to Military Government. Its duties, they felt,

would be eased by the continuing recovery of major works from their refuges, which would obviate the need for replacement in kind from the German patrimony. No one in this group had any knowledge of the quite different plans being made at the highest levels of the United States government, though they were aware that not everyone thought as they did. In his diary Walker noted in passing that Colonel Leslie Jefferson, head of the division of which MFAA was a branch, was “a hard boiled regular Army colonel with no interest whatever in art. He wants U.S. to get something out of this war. Dislikes French.”

25

Other books

10 Nights by Michelle Hughes, Amp, Karl Jones

A Corpse at St Andrew's Chapel by Mel Starr

Night Resurrected by Joss Ware

Chasing Gideon by Karen Houppert

Conspiracy by Black, Dana

Siren's Fury by Mary Weber

Phantom Fae by Terry Spear

Scarlet Fever - Hill Country 2 by Hunter, Sable

Three Rivers by Chloe T Barlow

The Privateer by Zellmann, William