The Reenchantment of the World (2 page)

Read The Reenchantment of the World Online

Authors: Morris Berman

Translated into everyday life, what does this disenchantment mean?

It means that the modern landscape has become a scenario of "mass

administration and blatant violence,"2 a state of affairs now clearly

perceived by the man in the street. The alienation and futility that

characterized the perceptions of a handful of intellectuals at the

beginning of the century have come to characterize the consciousness of

the common man at its end. Jobs are stupefying, relationships vapid and

and transient, the arena of politics absurd. In the vacuum created by the

collapse of traditional values, we have hysterical evangelical revivals,

mass conversions to the Church of the Reverend Moon, and a general retreat

into the oblivion provided by drugs, television, and tranquilizers. We

also have a desperate search for therapy, by now a national obsession,

as millions of Americans try to reconstruct their lives amidst a pervasive

feeling of anomie and cultural disintegration. An age in which depression

is a norm is a grim one indeed.

Perhaps nothing is more symptomatic of this general malaise than the

inability of the industrial economies to provide meaningful work. Some

years ago, Herbert Marcuse described the blue- and white-collar classes in

America as "one-dimensional." "When technics becomes the universal form

of material production," he wrote, "it circumscribes an entire culture;

it projects a historical totality -- a 'world.'" One cannot speak of

alienation as such, he went on, because there is no longer a self to be

alienated. We have all been bought off, we all sold out to the System

long ago and now identify with it completely. 'People recognize themselves

in their commodities," Marcuse concluded; they have become what they own.3

Marcuse's is a plausible thesis. We all know the next-door neighbor who

is out there every Sunday, lovingly washing his car with an ardor that is

almost sexual. Yet the actual data on the day-to-day life of the middle

and working classes tend to refute Marcuse's notion that for these people,

self and commodities have merged, producing what he terms the "Happy

Consciousness." To take only two examples, Studs Terkel's interviews with

hundreds of Americans, drawn from all walks of life, revealed how hollow

and meaningless they saw their own vocations. Dragging themselves to work,

pushing themselves through the daily tedium of typing, filing, collecting

insurance premiums, parking cars, interviewing welfare applicants,

and largely fantasizing on the job -- these people, says Terkel, are no

longer characters out of Charles Dickens, but out of Samuel Beckett.4

The second study, by Sennett and Cobb, found that Marcuse's notion of

the mindless consumer was totally in error. The worker is not buying

goods because he identifies with the American Way of Life, but because

he has enormous anxiety about his self, which he feels possessions

might assuage. Consumerism is paradoxically seen as a way

out

of a

system that has damaged him and that he secretly despises; it is a way

of trying to keep

free

from the emotional grip of this system.5

But keeping free from the System is not a viable option. As technological

and bureaucratic modes of thought permeate the deepest recesses of our

minds, the preservation of psychic space has become almost impossible.6

"High-potential candidates for management positions in American

corporations customarily undergo a type of finishing-school education

that teaches them how to communicate persuasively, facilitate social

interaction, read body language, and so on. This mental framework is

then imported into the sphere of personal and sexual relations. One

thus learns, for example, how to discard friends who may prove to be

career obstacles and to acquire new acquaintances who will assist in

one's advancement. The employee's wife is also evaluated as an asset or

liability in terms of her diplomatic skills. And for most males in the

industrial nations, the sex act itself has literally become a project,

a matter of carrying out the proper techniques so as to achieve the

prescribed goal and thus win the desired approval. Pleasure and intimacy

are seen almostas a hindrance to the act. But once the ethos of technique

and management has permeated the spheres of sexuality and friendship,

there is literally no place left to hide. The "widespread climate of

anxiety and neurosis" in which we are immersed is thus inevitable.7

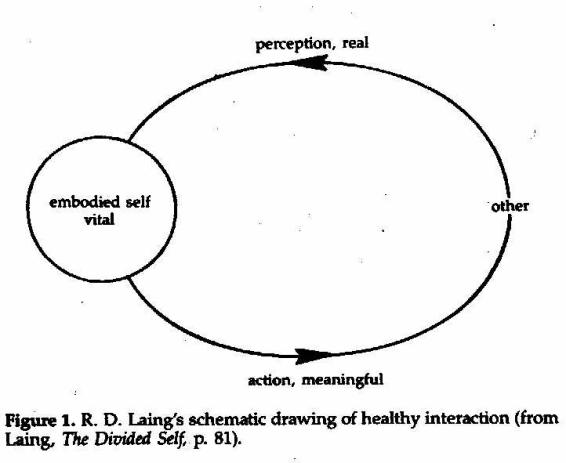

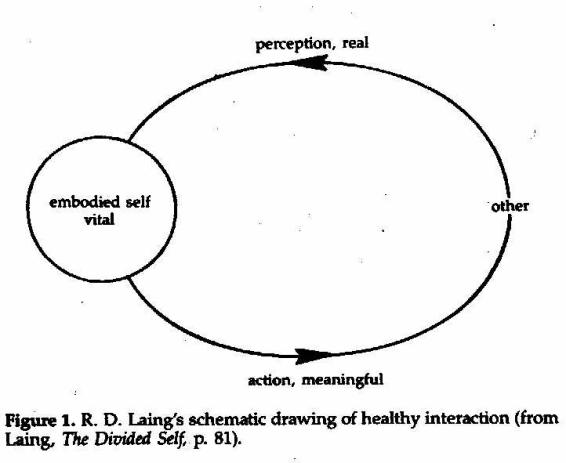

workings of the System most completely. In a study that purported to

be about schizophrenia, but that was for the most part a profile of

the psychopathology of everyday Life, R.D. Laing showed how the psyche

splits, creating false selves, in an attempt to protect itself from

all this manipulation.8 If we were asked to characterize our usual

relations with other persons, we might (as a first guess) describe them

as pictured in Figure 1 (see above). Here we have self and other in

direct interaction, engaging each other in an immediate way. As a result,

perception is real, action is meaningful, and the self feels embodied,

vital (enchanted). But as the discussion above clearly indicates, such

direct interaction almost never takes place. We are "whole" to almost no

one, least of all ourselves. Instead we move in a world of social roles,

interaction rituals, and elaborate game-playing that forces us to try

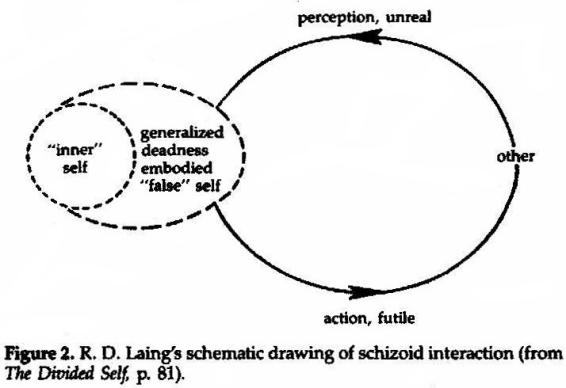

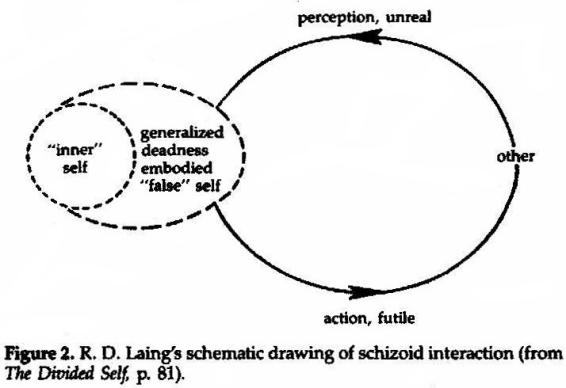

to protect the self by developing what Laing calls a "false-self system."

the interaction and leaving the body -- now perceived as false, or dead

(disenchanted) -- to deal with the other in a way that is pure theater,

while the "inner" self looks on like a scientific observer. Perception

is thus unreal, and action correspondingly futile. As Laing points out,

we retreat into fantasies at work -- and in "love -- and establish a

false self (identified with the body and its mechanical actions) which

performs the rituals necessary for us to succeed in our tasks. This

process begins sometime during the third year of life, is rexnforced in

kindergarten and grammar school, continues on into the dreary reality

of high school, and finally becomes the daily fare of working life.9

Everyone, says Laing -- executives, physicians, waiters, or whatever --

playacts, manipulates, in order to avoid being manipulated himself. The

aim is the protection of the self, but since that self is in fact cut

off from any meaningful intercourse, it suffocates. The environment

becomes increasingly unreal as human beings distance themselves from the

events of their own lives. As this process accelerates, the self begins

to fight back, to nag itself (and thus create a further split) about the

existential guilt it has come to feel. We are haunted by our phoniness,

our playacting, our flight from trying to become what we truly are or

could be. As the guilt mounts, we silence the nagging voice with drugs,

alcohol, spectator sports -- anything to avoid facing the reality of

the situation. When the self-mystification we practice, or the effect of

the pills, wears off, we are left with the terror of our own betrayal,

and the emptiness of our manipulated "successes."

as to defy comprehension. There is now a significant suicide rate among

the seven-to-ten age group, and teenage suicides tripled between 1966 and

1976 to roughly thirty per day. More than half the patients in American

mental hospitals are under twenty-one. In 1977, a survey of nine- to

eleven-year-olds on the West Coast found that nearly half the children

were regular users of alcohol, and that huge numbers in this age group

regularly came to school drunk. Dr. Darold Treffert, of Wisconsin's Mental

Health Institute, observed that millions of children and young adults are

now plagued by a gnawing emptiness or meaninglessness expressed not as a

fear of what may happen to them, but rather as a fear that nothing will

happen to them." Official figures from government reports released during

1971-72 recorded that the United States has 4 million schizophrenics, 4

million seriously disturbed children, 9 million alcoholics, and 10 million

people suffering from severely disabling depression. In the early 1970s,

it was reported that 25 million adults were using Valium; by 1980, Food

and Drug Administration figures indicated that Americans were downing

benzodiazepines (the class of tranquilizers which includes Valium) at a

rate of 5 billion pills a year. Hundreds of thousands of the nation's

children, according to "The Myth of the Hyperactive Child" by Peter

Schrag and Diane Divoky (1975), are being drugged in the schools, and

one-fourth of the American female population in the thirty-to-sixty age

group uses psychoactive prescription drugs on a regular basis. Articles in

popular magazines such as "Cosmopolitan" urge sufferers from depression

to drop in to the local mental hospital for drugs or shock treatments,

so that they can return to their jobs as quickly as possible. "The drug

and the mental hospital," writes one political scientist, "have become

the indispensable lubricating oil and reservicing factory needed to

prevent the complete breakdown of the human engine."10

Russia are world leaders in the consumption of hard liquor; the

suicide rate in France has been growing steadily; in West Germany,

the suicide rate doubled between 1966 and 1976.11 The insanity of Los

Angeles and Pittsburgh is archetypal, and the "misery index" has been

climbing in Leningrad, Stockholm, Milan, Frankfurt and other cities

since midcentury. If America is the frontier of the Great Collapse,

the other industrial nations are not far behind.

not

witnessing a peculiar

twist in the fortunes of postwar Europe and America, an aberration that

can be tied to such late twentieth-century problems as inflation, loss of

empire, and the like. Rather, we are witnessing the inevitable outcome

of a logic that is already centuries old, and which is being played out

in our own lifetime. I am not trying to argue that science is the cause

of our predicament; causality is a type of historical explanation which

I find singularly unconvincing. What I am arguing is that the scientific

world view is

integral

to modernity, mass society, and the situation

described above. It is our consciousness, in the Western industrial

nations -- uniquely so -- and it is intimately bound up with the emergence

of our way of life from the Renaissance to the present. Science, and our

way of life, have been mutually reinforcing, and it is tor this reason

that the scientific world view has come under serious scrutiny at the

same time that the industrial nations are beginning to show signs of

severe strain, if not actual disintegration.

solutions I dimly perceive, are epochal, and this is all the more reason

not to relegate them to the realm of theoretical abstraction. Indeed,

I shall argue that such fundamental transformations impinge upon the

details of our daily lives far more directly than the things we may think

to be most urgent: this Presidential candidate, that piece of pressing

legislation, and so on. There have been other periods in human history

when the accelerated pace of transformation has had such an impact on

individual lives, the Renaissance being the most recent example prior

to the present. During such periods, the meaning of individual lives

begins to surface as a disturbing problem, and people become preoccupied

with the meaning of meaning itself. It appears a necessary concomitant

of this preoccupation that such periods are characterized by a sharp

increase in the incidence of madness, or more precisely, of what is seen

to define madness.12 For value systems hold us (

It means that the modern landscape has become a scenario of "mass

administration and blatant violence,"2 a state of affairs now clearly

perceived by the man in the street. The alienation and futility that

characterized the perceptions of a handful of intellectuals at the

beginning of the century have come to characterize the consciousness of

the common man at its end. Jobs are stupefying, relationships vapid and

and transient, the arena of politics absurd. In the vacuum created by the

collapse of traditional values, we have hysterical evangelical revivals,

mass conversions to the Church of the Reverend Moon, and a general retreat

into the oblivion provided by drugs, television, and tranquilizers. We

also have a desperate search for therapy, by now a national obsession,

as millions of Americans try to reconstruct their lives amidst a pervasive

feeling of anomie and cultural disintegration. An age in which depression

is a norm is a grim one indeed.

Perhaps nothing is more symptomatic of this general malaise than the

inability of the industrial economies to provide meaningful work. Some

years ago, Herbert Marcuse described the blue- and white-collar classes in

America as "one-dimensional." "When technics becomes the universal form

of material production," he wrote, "it circumscribes an entire culture;

it projects a historical totality -- a 'world.'" One cannot speak of

alienation as such, he went on, because there is no longer a self to be

alienated. We have all been bought off, we all sold out to the System

long ago and now identify with it completely. 'People recognize themselves

in their commodities," Marcuse concluded; they have become what they own.3

Marcuse's is a plausible thesis. We all know the next-door neighbor who

is out there every Sunday, lovingly washing his car with an ardor that is

almost sexual. Yet the actual data on the day-to-day life of the middle

and working classes tend to refute Marcuse's notion that for these people,

self and commodities have merged, producing what he terms the "Happy

Consciousness." To take only two examples, Studs Terkel's interviews with

hundreds of Americans, drawn from all walks of life, revealed how hollow

and meaningless they saw their own vocations. Dragging themselves to work,

pushing themselves through the daily tedium of typing, filing, collecting

insurance premiums, parking cars, interviewing welfare applicants,

and largely fantasizing on the job -- these people, says Terkel, are no

longer characters out of Charles Dickens, but out of Samuel Beckett.4

The second study, by Sennett and Cobb, found that Marcuse's notion of

the mindless consumer was totally in error. The worker is not buying

goods because he identifies with the American Way of Life, but because

he has enormous anxiety about his self, which he feels possessions

might assuage. Consumerism is paradoxically seen as a way

out

of a

system that has damaged him and that he secretly despises; it is a way

of trying to keep

free

from the emotional grip of this system.5

But keeping free from the System is not a viable option. As technological

and bureaucratic modes of thought permeate the deepest recesses of our

minds, the preservation of psychic space has become almost impossible.6

"High-potential candidates for management positions in American

corporations customarily undergo a type of finishing-school education

that teaches them how to communicate persuasively, facilitate social

interaction, read body language, and so on. This mental framework is

then imported into the sphere of personal and sexual relations. One

thus learns, for example, how to discard friends who may prove to be

career obstacles and to acquire new acquaintances who will assist in

one's advancement. The employee's wife is also evaluated as an asset or

liability in terms of her diplomatic skills. And for most males in the

industrial nations, the sex act itself has literally become a project,

a matter of carrying out the proper techniques so as to achieve the

prescribed goal and thus win the desired approval. Pleasure and intimacy

are seen almostas a hindrance to the act. But once the ethos of technique

and management has permeated the spheres of sexuality and friendship,

there is literally no place left to hide. The "widespread climate of

anxiety and neurosis" in which we are immersed is thus inevitable.7

workings of the System most completely. In a study that purported to

be about schizophrenia, but that was for the most part a profile of

the psychopathology of everyday Life, R.D. Laing showed how the psyche

splits, creating false selves, in an attempt to protect itself from

all this manipulation.8 If we were asked to characterize our usual

relations with other persons, we might (as a first guess) describe them

as pictured in Figure 1 (see above). Here we have self and other in

direct interaction, engaging each other in an immediate way. As a result,

perception is real, action is meaningful, and the self feels embodied,

vital (enchanted). But as the discussion above clearly indicates, such

direct interaction almost never takes place. We are "whole" to almost no

one, least of all ourselves. Instead we move in a world of social roles,

interaction rituals, and elaborate game-playing that forces us to try

to protect the self by developing what Laing calls a "false-self system."

the interaction and leaving the body -- now perceived as false, or dead

(disenchanted) -- to deal with the other in a way that is pure theater,

while the "inner" self looks on like a scientific observer. Perception

is thus unreal, and action correspondingly futile. As Laing points out,

we retreat into fantasies at work -- and in "love -- and establish a

false self (identified with the body and its mechanical actions) which

performs the rituals necessary for us to succeed in our tasks. This

process begins sometime during the third year of life, is rexnforced in

kindergarten and grammar school, continues on into the dreary reality

of high school, and finally becomes the daily fare of working life.9

Everyone, says Laing -- executives, physicians, waiters, or whatever --

playacts, manipulates, in order to avoid being manipulated himself. The

aim is the protection of the self, but since that self is in fact cut

off from any meaningful intercourse, it suffocates. The environment

becomes increasingly unreal as human beings distance themselves from the

events of their own lives. As this process accelerates, the self begins

to fight back, to nag itself (and thus create a further split) about the

existential guilt it has come to feel. We are haunted by our phoniness,

our playacting, our flight from trying to become what we truly are or

could be. As the guilt mounts, we silence the nagging voice with drugs,

alcohol, spectator sports -- anything to avoid facing the reality of

the situation. When the self-mystification we practice, or the effect of

the pills, wears off, we are left with the terror of our own betrayal,

and the emptiness of our manipulated "successes."

as to defy comprehension. There is now a significant suicide rate among

the seven-to-ten age group, and teenage suicides tripled between 1966 and

1976 to roughly thirty per day. More than half the patients in American

mental hospitals are under twenty-one. In 1977, a survey of nine- to

eleven-year-olds on the West Coast found that nearly half the children

were regular users of alcohol, and that huge numbers in this age group

regularly came to school drunk. Dr. Darold Treffert, of Wisconsin's Mental

Health Institute, observed that millions of children and young adults are

now plagued by a gnawing emptiness or meaninglessness expressed not as a

fear of what may happen to them, but rather as a fear that nothing will

happen to them." Official figures from government reports released during

1971-72 recorded that the United States has 4 million schizophrenics, 4

million seriously disturbed children, 9 million alcoholics, and 10 million

people suffering from severely disabling depression. In the early 1970s,

it was reported that 25 million adults were using Valium; by 1980, Food

and Drug Administration figures indicated that Americans were downing

benzodiazepines (the class of tranquilizers which includes Valium) at a

rate of 5 billion pills a year. Hundreds of thousands of the nation's

children, according to "The Myth of the Hyperactive Child" by Peter

Schrag and Diane Divoky (1975), are being drugged in the schools, and

one-fourth of the American female population in the thirty-to-sixty age

group uses psychoactive prescription drugs on a regular basis. Articles in

popular magazines such as "Cosmopolitan" urge sufferers from depression

to drop in to the local mental hospital for drugs or shock treatments,

so that they can return to their jobs as quickly as possible. "The drug

and the mental hospital," writes one political scientist, "have become

the indispensable lubricating oil and reservicing factory needed to

prevent the complete breakdown of the human engine."10

Russia are world leaders in the consumption of hard liquor; the

suicide rate in France has been growing steadily; in West Germany,

the suicide rate doubled between 1966 and 1976.11 The insanity of Los

Angeles and Pittsburgh is archetypal, and the "misery index" has been

climbing in Leningrad, Stockholm, Milan, Frankfurt and other cities

since midcentury. If America is the frontier of the Great Collapse,

the other industrial nations are not far behind.

not

witnessing a peculiar

twist in the fortunes of postwar Europe and America, an aberration that

can be tied to such late twentieth-century problems as inflation, loss of

empire, and the like. Rather, we are witnessing the inevitable outcome

of a logic that is already centuries old, and which is being played out

in our own lifetime. I am not trying to argue that science is the cause

of our predicament; causality is a type of historical explanation which

I find singularly unconvincing. What I am arguing is that the scientific

world view is

integral

to modernity, mass society, and the situation

described above. It is our consciousness, in the Western industrial

nations -- uniquely so -- and it is intimately bound up with the emergence

of our way of life from the Renaissance to the present. Science, and our

way of life, have been mutually reinforcing, and it is tor this reason

that the scientific world view has come under serious scrutiny at the

same time that the industrial nations are beginning to show signs of

severe strain, if not actual disintegration.

solutions I dimly perceive, are epochal, and this is all the more reason

not to relegate them to the realm of theoretical abstraction. Indeed,

I shall argue that such fundamental transformations impinge upon the

details of our daily lives far more directly than the things we may think

to be most urgent: this Presidential candidate, that piece of pressing

legislation, and so on. There have been other periods in human history

when the accelerated pace of transformation has had such an impact on

individual lives, the Renaissance being the most recent example prior

to the present. During such periods, the meaning of individual lives

begins to surface as a disturbing problem, and people become preoccupied

with the meaning of meaning itself. It appears a necessary concomitant

of this preoccupation that such periods are characterized by a sharp

increase in the incidence of madness, or more precisely, of what is seen

to define madness.12 For value systems hold us (

Other books

The Perfect Scream by James Andrus

Lifesaving for Beginners by Ciara Geraghty

Dare to Breathe by Homer, M.

The Great Fire by Lou Ureneck

Cursed by Jennifer L. Armentrout

VEX: Valley Enforcers, #1 by Walters, Abi

Claire and Present Danger by Gillian Roberts

Refresh by S. Moose

Dead in the Water by Ted Wood

The Tale-Teller by Susan Glickman