The Reenchantment of the World (4 page)

Read The Reenchantment of the World Online

Authors: Morris Berman

that the knowledge of nature comes about under artificial conditions. Vex

nature, disturb it, alter it, anything -- but do not leave it alone. Then,

and only then, will you know it. The elevation of technology to the

level of a philosophy had its concrete embodiment in the concept of

the experiment, an artificial situation in which nature's secrets are

extracted, as it were, under duress.

the control of the environment by mechanical means in the form of

windmills or plows is almost as old as homo sapiens himself. But the

elevation of this control to a philosophical level was an unprecedented

step in the history of human thought. Despite the extreme sophistication

of, for example, Chinese-technology down to the fifteenth century A.D.,

it never had occurred to the Chinese (or to Westerners, for that matter)

to equate mining or gunpowder manufacture with pure knowledge, let alone

with the key to acquiring such knowledge.7 Science did not, then, grow up

"around" Bacon, and his own lack of experimentation is irrelevant. The

details of what constituted an experiment were worked out later, in the

course of the seventeenth century. The overall framework of scientific

experimentation, the technological notion of the questioning of nature

under duress, is the major Baconian legacy.

that the mind of the experimenter, when it adopts this new perspective,

will also be under duress. Just as nature must not be allowed to go

its own way, says Bacon in the Preface to the work, so it is necessary

that "the mind itself be from the very outset not left to take its own

course, but guided at every step; and the business be done as if by

machinery." To know nature, treat it mechanically; but then your mind

must behave mechanically as well.

verbiage, and felt that nothing less than certainty would do for a true

philosophy of nature. The "Discourse," written some seventeen years

after the "New Organon," is in part an intellectual autobiography. Its

author emphasizes the worthlessness of the ancient learning to himself

personally, and in doing so implicates the rest of Europe as well. I

had the best education France had to offer, he says (he studied at

a Jesuit seminary, the Ecole de La Flèche); yet I learned nothing I

could call certain. "As far as the opinions which I had been receiving

since my birth were concerned, I could not do better than to reject them

completely for once in my life time. . . . ."8 As with Bacon, Descartes

goal is not to "engraft" or "superinduce," but to start anew. But how

vastly different is Descartes' starting point! It is no use collecting

data or examining nature straight off, says Descartes; there will be time

enough for that once we learn how to think correctly. Without having a

method of clear thinking which we can apply, mechanically and rigorously,

to every phenomenon we wish to study, our examination of nature will of

necessity be faulty. Let us, then, block out the external world and sort

out the nature of right thinking itself.

I thought I knew up to this point. This act was not undertaken for

its own sake, or to serve some abstract principle of rebellion, but

proceeded from the realization that all the sciences were at present

on shaky ground. "All the basic principles of the sciences were taken

from philosophy," he writes, "which itself had no certain ones. Since

my goal was certainty, "I resolved to consider almost as false any

opinion which was merely plausible." Thus the starting point of the

scientific method, insofar as Descartes was concerned, was a healthy

skepticism. Certainly the mind ought to be able to know the world, but

first it must rid itself of credulity and medieval rubbish, with which

it had become inordinately cluttered. "My whole purpose," he points out,

"was to achieve greater certainty and to reject the loose earth and sand

in favor of rock and clay."

depressing conclusion: there was nothing at all of which one could

be certain. For all I know, he writes in the "Meditations on First

Philosophy" (1641), there could be a total disparity between reason

and reality. Even if I assert that God is good, and is not deceiving me

when I try to equate reason with reality, how do I know there is not a

malignant demon running about who confuses me? How do I know that 2 + 2

do not make 5, and that this demon does not deceive me, every time I make

the addition, into believing the numbers add up to 4? But even if this

were the case, concludes Descartes, there is one thing I do know: that I

exist. For even if I am deceived, there is obviously a "me" who is being

deceived. And thus, the bedrock certainty that underlies everything: I

think, therefore I am. For Descartes, thinking was identical to existing.

more than just my own existence. Confronted with the rest of knowledge,

however, Descartes finds it necessary to demonstrate (which he does

most unconvincingly) the existence of a benevolent Deity. The existence

of such a God immediately guarantees the propositions of mathematics,

which alone among the sciences relies on pure mental activity. There

can be no deception when I sum the angles of a triangle; the goodness

of God guarantees that my purely mental operations will be correct,

or as Descartes says, clear and distinct. And extrapolating from this,

we see that knowledge of the external world will also have certitude

if its ideas are clear and distinct, that is, if it takes geometry as

its model (Descartes never really did define, to anybody's satisfaction,

the terms "clear" and "distinct"). Science, says Descartes, must become a

"universal mathematics"; numbers are the only test of certainty.

Whereas the latter sees the foundations of knowledge in sense data,

experiment, and the mechanical arts, Descartes sees only confusion in such

subjects and finds clarity in the operations of the. mind, alone.9 Thus

the method he sets forth for acquiring gnowleage is based, he tells us,

on geometry. The first step is the statement of the problem that, in its

complexity, will be obscure and confused. The second step is breaking

the problem down into its simplest units, its component parts. Since

one can perceive directly and immediately what is clear and distinct in

these simplest units, one can finally reassemble the whole structure in a

logical fashion. Now the problem, complex though it may be, is no longer

unknown (obscure and confused), because we ourselves have first broken it

down and then put it back together again. Descartes was so impressed with

this discovery that he regarded it as the key, indeed the only key, to

the knowledge of the world. "Those long chains of reasoning," he writes,

"so simple and easy, which enabled the geometricians to reach the most

difficult demonstrations, had made me wonder whether all things knowable

to men might not fall into a similar logical sequence."10

his grappling with the concept of experiment based on technology certainly

underlie much of our current scientific thought, the implications drawn

from the Cartesian corpus exercised a staggering impact on the subsequent

history of Western consciousness and (despite the differences with Bacon)

served to confirm the technological paradigm -- indeed, even helped to

launch it on its way. Man's activity as a thinking being -- and that

is his essence, according to Descartes -- is purely mechanical. The

mind is in possession of a certain method. It confronts the world as a

separate object. It applies this method to the object, again and again

and again, and eventually it will know all there is to know. The method,

furthermore, is also mechanical. The problem is broken down into its

components, and the simple act of cognition (the direct perception)

has the same relationship to the knowledge of the whole problem that,

let us say, an inch has to a foot: one measures (perceives) a number of

times, and then sums the results. Subdivide, measure, combine; subdivide,

measure, combine.

consists of subdividing a thing into its smallest components. The essence

of atomism, whether material or philosophical, is that a thing consists

of the sum of its parts, no more and no less. And Descartes' greatest

legacy was surely the mechanical philosophy, which followed directly

from this method. In the "Principles of Philosophy" (1644) he showed

that the logical linking of clear and distinct ideas led to the notion

that the universe was a vast machine, wound up by God to tick forever,

and consisting of two basic entities: matter and motion. Spirit, in

the form of God, hovers on the outside of this billlard-ball universe,

but plays no direct part in it. All nonmaterial phenomena ultimately

have a material basis. The action of magnets, attracting each other

over a distance, may seem to be nonmaterial, says Descartes, but the

application of the method can and will ultimately uncover a particulate

basis for their behavior. What Descartes does, really, is provide Bacon's

technological paradigm with strong philosophical teeth. The mechanical

philosophy, the use of mathematics, and the formal application of his

four-step method enable the manipulation of the environment to take

place with some sort of logical regularity.

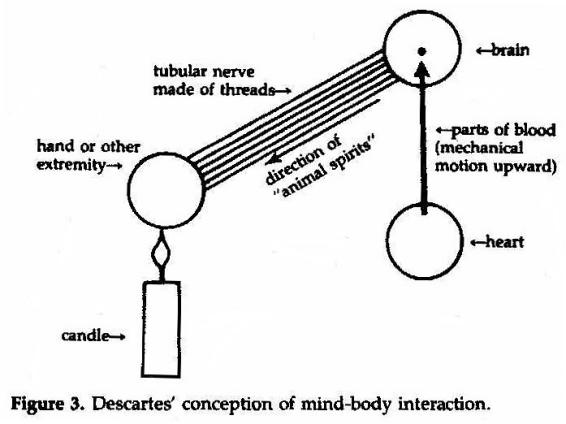

that man can know all there is to know by way of his reason, included

for Descartes the assumption that mind and body, subject and object,

were radically disparate entities. Thinking, it would seem, separates me

from the world I confront. I perceive my body and its functions, but "I"

am not my body. I can learn about the (mechanical) behavior of my body by

applying the Cartesian method -- and Descartes does this in his treatise

"On Man" (1662) -- but it always remains the object of my perception. Thus

Descartes depicted the operation of the human body by means of analogy to

a water fountain, with mechanical reflex action being the model of most,

if not all, human behavior. The mind, res cogitans ("thinking substance"),

is in a totally different category from the body, res extensa ("extended

substance"), but they do have a mechanical interaction that we can

diagram as in Figure 3, below. If the hand touches a flame, the fire

particles attack the finger, pulling a thread in the tubular nerve which

releases the "animal spirits" (conceived as mechanical corpuscles) in the

brain. These then run down the tube and jerk the muscles in the hand.11

and that of Laing's "false-self system" depicted in the Introduction

(see Figure 2). Schizophrenics typically regard their bodies as "other,"

"not-me." In Descartes' diagram, too, brain (inner self) is the detached

observer of the parts of the body; the interaction is mechanical, as

though one saw oneself behaving as a robot -- a perception that is easily

extended to the rest of the world. To Descartes, this mind-body split was

true of

all

perception and behavior, such that in the act of thinking

one perceived oneself as a separate entity "in here" confronting things

"out-there." This schizoid duality lies at the heart of the Cartesian

paradigm.

of knowledge on geometry, also served to reaffirm, if not actually

canonize, the Aristotelian principle of noncontradiction. According to

this principle, a thing cannot both be and not be at the same time. When

I strike the letter "A" on my typewriter, I get an "A" on the paper

(assuming the machine is working properly), not a "B." The cup of coffee

sitting to the right of me could be put on a scale and found to have a

weight of, say, 5.24 ounces, and this fact means that the object does not

weigh ten pounds or two grams. Since the Cartesian paradigm recognizes

no self-contradictions in logic, and since logic (or geometry), according

to Descartes, is the way nature behaves and is known to us, the paradigm

allows for no self-contradictions in nature.

it will suffice to note that real life operates dialectically, not

critically.12 We love and hate the same thing simultaneously, we fear

what we most need, we recognize ambivalence as a norm rather than an

aberration. Descartes' devotion to critical reason led him to identify

dreams, which are profoundly dialectical statements, as the model of

unreliable knowledge. Dreams, he tells us in the "Meditations on First

Philosophy," are not clear and distinct, but invariably obscure and

confused. They are filled with frequent self-contradictions, and possess

(from the viewpoint of critical reason) neither internal nor external

coherence. For example, I might dream that a certain person I know is my

father, or even that I am my father, and that I am arguing with him. But

this dream is (from a Cartesian point of view) internally incoherent,

because I am simply not my father, nor can he be himself and someone

else as well; and it is externally incoherent, because upon waking, no

matter how real it all seems for a moment, I soon realize that my father

is three thousand miles away, and that the supposed confrontation never

took place. For Descartes, dreams are not material in nature, cannot be

measured, and are not clear, and distinct. Given Descartes' criteria,

then, they contain no reliable information.

Other books

The Beast of Blackslope by Tracy Barrett

Love Is My Reason by Mary Burchell

Cyn (Moon Hunter's Inc. Book 2) by Catty Diva

The Eyes of the Dead by Yeates, G.R.

The Iris Fan by Laura Joh Rowland

On the Grind (2009) by Cannell, Stephen - Scully 08

The Mermaids Singing by Val McDermid

The Coming of the Dragon by Rebecca Barnhouse

The Golden Spiders by Rex Stout

Captive of Fate by McKenna, Lindsay