The Reenchantment of the World (26 page)

Read The Reenchantment of the World Online

Authors: Morris Berman

sought to demonstrate in scientific (and later, scientistic) terms. To

do so one must show that unconscious knowledge is essentially body

knowledge or, more plainly put, that the body and the unconscious are

one and the same thing, and this was precisely Reich's major contribution

to psychoanalysis. A brief sketch of his work will help to substantiate

our argument for the continuity of holistic consciousness.

For him, as for Descartes, all affect was ultimately rooted in the

mechanical arrangement of corpuscles (or neurons), a bolief made explicit

in his unpublished "Scientific Project" of 1895 and retained by Western

medicine to this day. Mind and body, or ego and instinct, are rigidly

distinct entities, and all intrapsychic processes (like everything else)

are essentially mechanical in nature. From this strictly materialistic

analysis, with its elaboration in terms of thermodynamic and hydraulic

energy transfers (conversion, cathexis, resistance, etc.), it followed

that neurotic symptoms were adventitious, or mechanically separable. In

other words, a neurosis for Freud was an alien element in an otherwise

healthy organism. It was formed by repressing a painful event and

thereby removing it from conscious awareness; the neurosis could itself

be removed by techniques (notably free association) designed to make

the unconscious memory conscious.

this sensible, intellectual approach does not work. Freud himself was

aware of its limitations and did emphasize that the therapy session

must flush out, or "abreact," the emotion that accompanied the original

repression. Yet his commitment was ultimately to the supposediy curative

power of the intellect. "I can only wonder what neurotics will do

in the future," he remarked naively to Jung, "when all their symbols

have been unmasked. It will then bo impossible to have a neurosis."29

That analytical cognition made little difference for affect, or that

mimesis might be knowledge, were notions that Freud was no more willing

to accept than Plato had been. Nor did he ever grasp how passionately,

even erotically, he was attached to the concept of intellectual knowing.

approach. His central argument was that what we call "personality," or

"character," was itself a neurosis; or, as psychiatrist John Bowlby has

put it, a posture of defense against the threat of object-loss. Against

Freud's mechanistic theory, with its idea of separable parts, Reich

advanced a holistic one: "

there cannot be a neurotic symptom

," he wrote,

"

without a disturbance of the character as a whole

. Symptoms are merely

peaks on the mountain ridge which the neurotic character represents."30

of the personality, which has a psychic aspect, the neurosis, and a

muscular one, the character armor. Early in life, he contended, the

spontaneous nature of the child is subjected to severe repression by its

parents, who fear such spontaneity (in particular, the lack of sexual and

sensual inhibition) and socialize it out of the child, as it was long

ago socialized out of them. By age four or five, the natural instincts

have been crushed or surrounded by a psychic defence structure that has

a muscular rigidity as its correlate. What is lost is the ability to

succumb to involuntary experience, to abandon control and lose oneself in

an activity; to obtain what Reich called (perhaps misleadingiy) "orgastic

gratification." The orgastically ungratified person develops an artificial

character and a fear of spontaneity. Whereas the healthy character is

in control of his or her armor, the neurotic character is controlled by

it. The emotions of the latter, including anger, anxiety, sexual desire,

or whatever, are rigidly held down by this muscular tension, and the

result is the stiff (or collapsed) posture and mechanical articulation

of the body that is observable almost everywhere in our society. This

neurotic character, or "modal personality,"31 encased in character

armor, might most appropriately be compared to a crustacean. Its entire

character is designed to fulfill the function of defense and protection

or, alternatively, acquisition and aggrandizement. It moves from crisis

to crisis, driven by a a desire for success and proud of its ability

to tolerate stress. Its armoring is not merely a defense against the

other, but against its own unconscious, its own body. The armor may

protect against pain and anger, but it also protects against everything

else. These emotions are held down by inverted values, such as compulsive

morality and social politeness -- the veneer of civilization. The

modal personality is thus a mixture of external conformity and internal

rebellion. It reproduces, like a sheep, the ideology of the society that

molded it in the first place, and thus its ideology (regardless of its

politics) is essentially life-negating. In reproducing that ideology,

the neurotic character produces its own suppression. Neurosis is not some

adventitious accretion, some fly in the ointment. It is, Reich argued,

an icon of personality and culture as a whole.

Newton, and have noted the relationship between his self-repression and

his system of the world. We have also argued that such a person was

the product of the rise of capitalism and the Puritan mentality that

accompanied it. In one of his earliest studies, Erich Fromm demonstrated

quite convincingly the connection between this so-called anal type,

with its preoccupation with orderliness, and the social typology of the

capitalist described by Werner Sombart and Max Weber. "The character

structure," wrote Reich, "is the congealed sociological process of a

given epoch." As Reich realized, such a type is hardly the prerogative

of capitalist society, for it exists in all industrial societies,

all societies based on production and efficiency rather than joy and

authenticity.32

had a strong political orientation, and did not believe that individual

cures could succeed apart from major social changes. But the project of

integrating individual with social change eluded him (as it has every

political theorist), and he was not able to clarify how a political

program could be forged out of authenticity or self-realization. On

the individual level, however, he had no doubts: authenticity meant,

specifically, body authenticity, the feeling of the continuity of

consciousness with the body which Descartes denied was possible. "The

philosophic underpinning of body authenticity," writes Peter Koestenbaum,

"is that the body is a metaphor for the fundamental structure of being

itself" -- a position, incidentally, with which no self-respecting

alchemist would disagree.33 The restoration of authenticity, of the sense

of authentic being-in-the-world, was thus not likely to be accomplished

through the intellect; a situation that for Reich explained the general

failure of Freudian analysis. Reich's specific mode of therapy went hand

in hand with his realization that Descartes was quite simply wrong,

that the mind/body dichotomy was an artificial construct. The whole

theory of character armor, which Reich believed was validated every

time a patient walked into his office, demonstrated that "muscular

attitudes and character attitudes have the same function in the psychic

mechanism." The psychiatrist could actually have greater success in

getting to the unconscious through the manipulation of the patient's body

than by the technique of free association. This manipulation loosened the

armor, producing not merely an abundance of twitchings and sensations,

but primitive emotions and a memory of the event during which these

emotions (instincts) were originally repressed. These emotions and

memories were not, in Cartesian formulation, causes or results of

body phenomena; rather, "they were simply these phenomena themselves

in the somatic realm." Somatic rigidity, wrote Reich, "represents the

most essential part in the process of repression," and each rigidity

"

contains the history and meaning of its origin.

" Armor in short, is the

form in which the experience of impaired functioning is preserved. Reich

concluded not only that the traditional mind/body dichotomy was in error,

but that Freud was wrong in arguing that the unconscious, like Kant's

'Ding an sich,' was not tangible. 'Put your hands on the body,' said

Reich, 'and you have put your hands on the unconscious.' The eruption of

ancient childhood memories and their affective accompaniment in hundreds

of patients demonstrated to him that the unconscious can be contacted

directly in the form of the biological energy of the body and the various

twists and turns that have blocked and distorted it.

demonstrate clinically, is something we are all intuitively aware of,

and which can be explored without undergoing Reichian analysis. All of us

have had the experience, for example, of waking up and forgetting what we

were just dreaming about. We may then slowly shift our position in bed,

only to have part or all of the dream come back; and different positions

will retrieve different scenes of the dream. In dreaming, apparently,

certain imagery from the body tissues is released as we toss and turn in

our sleep; or alternatively, these images got "fixed" in the body while

it was in certain positions. Recalling a particular image is therefore

often dependent on assuming the bodily configuration that was present

during the original dream sequence.

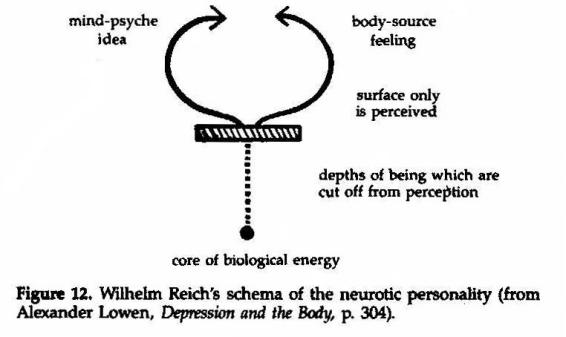

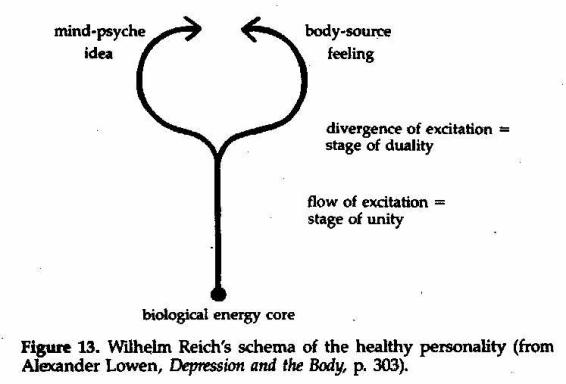

Chapter I is in reality the schema of the modern schizoid

personality. This personality can also be schematized as in

Figure 12. What we take as normal is thus a distortion of a

very different, non-Cartesian relationship that a person can

and should have with him- or herself, as illustrated in Figure 13.

only

duality,

only

subject/object distinction, the stage of unity indicated in Figure 13

is permanently inaccessible to him or her. But as we have seen, this

unity is the primary reality of all human being and cognition, and

to be out of touch with it is to be suffering from severe internal

distortion. The point is that the modal personality, having a distorted

internal relationship, must necessarily have a distorted external

one. He or she will see the world the way Newton saw it in his later

years. Surface appearances will be confused with the real thing. Truly

accurate perception depends upon maintaining contact with the biological

core, for only then can one return to it at will, that is, abandon control

and merge with the object. And it was this ability to surrender control,

to obtain "orgastic gratification," or what I have referred to as the

mimetic experience, that Reich defined as the ability to love. Suspension

of ego thus lies at the core of loving, and all true experience of nature

depends on it.

sense of everything being alive and interrelated, is that the world

is sensual at its core; that this is the essence of reality. Tactile

experience can be taken as the root metaphor for mimesis in general. When

the Indian does a rain dance, for example, he is not assuming an

automatic response. There is no failed technology here, rather, he is

inviting the clouds to join him, to respond to the invocation. He is,

in effect, asking to make love to them, and like any normal lover they

may or may not be in the mood. This is the way nature works. By means of

this approach, the native learns about the reality of the situation, the

moods of the earth and the skies. He surrenders: mimesis, participation,

orgastic gratification. Western technology, on the other hand, seeds

the clouds by airplane. It takes nature by force, "masters" it, has no

time for mood or subtlety, and thus, along with the rain, we get noise,

pollution, and the potential disruption of the ozone layer. Rather than

put ourselves in harmony with nature, we seek to conquer it, and the

result is ecological destruction. Who, then, knows more about nature,

about "reality"? The person who caresses it, or the one who takes it by

force, vexes it, as Bacon urged? The epistemological corollary of Reich's

work is that having certainty about reality is dependent upon loving -- a

remarkable sort of conclusion. Conversely, perception based on mechanical

causality and the mind/body dichotomy is best put under the heading of

"impaired reality-testing," the clinical definition of insanity.

Other books

Mended Affections (The Affections Series Book 2) by Elizabeth Wills

Tell Me What Is Priceless (Siren Publishing Classic) by Kat Barrett

The Darling Buds of May by H.E. Bates

The Ripper's Wife by Brandy Purdy

The After Party by Anton Disclafani

Thicker than Blood by Madeline Sheehan

Murder in the Rue St. Ann by Greg Herren

Take it Deep (Take 2) by Roberts, Jaimie

Beauty Chorus, The by Brown, Kate Lord