The Reenchantment of the World (11 page)

Read The Reenchantment of the World Online

Authors: Morris Berman

outer, psychic and organic (or physical), do not exist. If you wish

to promote love, says Agrippa, eat pigeons; to obtain courage, lions'

hearts. A wanton woman, or charismatic man, possesses the same virtue

as a lodestone, that of attraction.10 Diamonds, on the other hand,

weaken the lodestone, and topaz weakens lust. Everything thus bears the

mark of the Creator, and knowledge, says Agrippa, consists of "a certain

participation," a (sensuous) sharing in His Divinity. This is a world

permeated with meaning, for it is according to these signatures that

everything belongs, has a place. "There is nothing found in the whole

world," he writes, "that hath not a spark of the virtue [of the world

soul]." "Every thing hath its determinate and particular place in the

exemplary world."

we have noted, magic and Hermeticism were in continual conflict with the

church. But this conflict, like the theory of knowledge that underlay it,

was also one of resemblance, for the medieval church (as we shall discuss

below) was steeped in magical practices and sacraments from which it

derived its power on the local level. Consequently, it would tolerate

no rivalry on this score.11 The important point, however, is that all

premodern knowledge had the same structure. As Michel Foucault tells us,

divination "is not a rival form of knowledge; it is part of the main body

of knowledge itself." Erudition and Hermeticism, Petrarch and Ficino,

ultimately inhabited the same mental universe.

can be dated) in the late sixteenth century, that so radically marks

off the medieval from the modern world; and nowhere is this more clearly

portrayed than in Cervantes' epic, "Don Quixote."12 The Don's adventures

are an attempt to decipher the world, to transform reality itself into a

sign. His journey is a quest for resemblances in a society that has come

to doubt their significance. Hence, that society judges him to be mad,

"quixotic." Where he sees the Shield of Mambrino, Sancho Panza can make

out only a barber's basin; where (to take the most famous example) he

perceives giants, Sancho sees only windmills. Hence the literal meaning

of 'paranoia': like knowledge. The division of psychic and material,

mind and body, symbolic and literal, has finally occurred. The madman

perceives resemblances that do not exist, that are seen as not signifying

anything at all. By 1600 he is "alienated in analogy," whereas four

or five decades earlier he was the typical educated European. For the

madman the crown makes the king, and Shakespeare captured the shift in the

definition of reality in his line, "All hoods do not monks make." Given

the meaninglessness of such associations, practices such as conjuring

could no longer be regarded as effective. "I can call spirits from the

vasty deep," says Glendower to Hotspur in "Henry IV, Part I." "Why so

can I, or so can any man," replies the latter; "But will they come when

you do call for them?"

with which we are very familiar. Glendower, on the other hand, sounds

the last chords of a world largely lost to our imaginations; a world of

resonance, resemblance, and incredible richness. Yet these chords may,

even today, echo vaguely in our subconscious minds. Before turning to

a more extended discussion of the collapse of original participation,

then, it will be worth our while to stay with it a bit longer, and see

if we cannot feel our way into this manner of thinking.

The pre-Homeric Greek, the medieval Englishman (to a lesser extent, of

course), and the present-day African tribesman know a thing precisely in

the act of identification, and this identification is as much sensual

as it is intellectual. It is a

totality

of experience: the "sensuous

intellect," if the reader can imagine such a thing. We have so lost

the ability to make this identification that we are left today with

only two experiences that consist of participating consciousness: lust

and anxiety. As I make love to my partner, as I immerse myself in her

body, I become increasingly "lost." At the moment of orgasm, I

am

the

act; there is no longer an "I" who experiences it. Panic has a similar

momentum, for if sufficiently terrified I cannot separate myself from

what is happening to me. In the psychotic (or mystic) episode, my skin

has no boundary. I am out of my mind, I have become my environment. The

essence of original participation is the

feeling

, the bodily perception,

that there stands behind the phenomena a "represented" that is of the

same nature as me -- 'mana,' God, the world spirit, and so on.13 This

notion, that subject and Object, self and other, man and environment,

are ultimately identical, is the holistic world view.

although sexual desire and panic remain the best examples. In truth --

and we shall treat this in detail in Chapter 5 -- participation is the

rule rather than the exception for modern man, although he is (unlike his

premodern counterpart) largely unconscious of it. Thus as I wrote the

first few pages of this chapter, down to this page, at least, I was so

absorbed in what I was doing that I had no sense of myself at all. The

same experience happens to me at a movie, a concert, or on a tennis

court. Nevertheless, the consciousness of official culture dictates my

"recognition" that I am not, and can never be, my experiences. Whereas

my premodern counterpart felt, and saw, that he was his experiences --

that his consciousness was not some special, independent consciousness --

I classify my own participation as some form of "recreation," and see

reality in terms of the inspection and evaluation Plato hoped men would

achieve. I thus see myself as an island, whereas my medieval or ancient

predecessor saw himself more like an embryo. And although there is no

going back to the womb, we can at least appreciate how comforting and

meaningful such a state of mind, and view of reality, truly was.

in the same world as I am, but somehow conceptualizing it differently

(i.e., incorrectly)? Doesn't the subject/object dichotomy represent a

distinct advance in human knowledge over this primitive, even orgiastic

identification of self and other? These questions, which are all

essentially asking the same thing, are the ones most crucial to the

history of consciousness, and require closer scrutiny. For there are only

two possibilities here. Either original participation, which was the basic

mode of human cognition (despite the gradual attenuation of that mode)

down to the late sixteenth century, was an elaborate self-deception; or

original participation really did exist, was an actual fact.14 We shall

try to decide between these two alternatives by means of an analysis of

the paradigm science of participation, alchemy.

attempt to find a chemical substance that, when added to lead, transformed

it into gold. Alternatively, it was the attempt to prepare a liquid,

the 'elixir vitae,' that would prolong human life indefinitely. Since

neither of these goals is attainable, the entire alchemical enterprise is

dismissed as a nonsensical episode (more than two thousand five hundred

years) in the history of science, a venture that could be viewed as tragic

were it not so silly in content. At most, modern science concedes that

the alchemists did, in the pursuit of their spurious ends, discover as

by-products various medicines and chemical substances that have some

utilitarian value.

truth. The quick production of the 'lapis,' or philosopher's stone,

whether in the form of gold or elixir, was certainly an irresistible

goal for many alchemists, and the term "puffer" was used to denote

the commercial opportunist and charlatan. "Of all men," wrote Agrippa,

"chymists are, the most perverse."15 Yet a brief perusal of medieval

and Renaissance alchemical plates, such as those collected by Carl

Jung, is enough to convince us that such charlatartry was hardly the

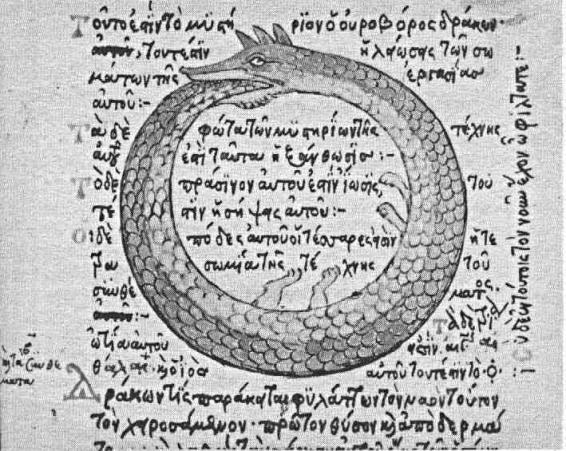

whole story to alchemy.16 What could these strange images (see Plates

2 - 6) possibly mean? A green and red snake swallowing its tail; an

"androgyne," or man-woman, joined at the waist with an eagle rising

behind it and a pile of dead eagles at its feet; a green lion biting

the sun, with blood (actually mercury) dripping from the resultant

"wound"; a human skeleton perched on a black sun; the sun casting a long

shadow behind the earth -- these and other images are so fantastic as

to defy comprehension. Surely, if all one wanted was health or wealth,

there was no need for the painstaking preparation of such elaborately

illustrated manuscripts. Mythopoeic artwork of this sort forces us to

abandon the simplistic utilitarian interpretation of alchemy and try,

instead, to chart the totally unfamiliar terrain of consciousness that

this bizarre imagery represents.

alchemy by means of clinical material from dream analysis, and then on

this basis to formulate the argument that alchemy was, in essence, a map

of the human unconscious. Central to Jungian psychology is the concept of

"individuation," the process whereby a person discovers and evolves his

Self, as opposed to his ego. The ego is a persona, a mask created and

demanded by everyday social interaction, and, as such, it constitutes

the center of our conscious life, our understanding of ourselves through

the eyes of others. The Self, on the other hand, is our true center,

our awareness of ourselves without outside interference, and it is

developed by bringing the conscious and unconscious parts of our mind

into harmony. Dream analysis is one way of achieving this harmony. We

can unlock our dream symbols and then act on the messages of our dreams

in waking life, which in turn begins to alter our dreams. But how to

analyze our dreams? They are frequently cryptic, and so often violate

causal sequence as to border on gibberish. But it is precisely here,

Jung discovered, that alchemy can make a crucial contribution. In fact,

it is by something like the doctrine of signatures that we are able to

figure out what our dreams mean.17

Plate 2. The Ourobouros, symbol of integration. Synosius, Ms. grec

2327, f.279. Phot. Bibl. nat. Paris.

which I have termed "dialectical," as opposed to the critical reason

characteristic of rational, or scientific, thought.18 As we saw earlier,

Descartes regarded dreams as perverse because they violated the principle

of noncontradiction. But this violation is not arbitrary; rather,

it emerges from a paradigm of its own, one that could well be called

alchemical. This paradigm has as a central tenet the notion that reality

is paradoxical, that things and their opposites are closely related, that

attachment and resistance have the same root. We know this on an intuitive

level already, for we speak of love-hate relationships, recognize that

what frightens us is most likely to liberate us, and become suspicious if

someone accused of wrongdoing protests his or her innocence too hotly. In

short, a thing can both be and not be at the same time, and as Jung,

Freud, and apparently the alchemists all understood, it usually is.

Other books

The Weird Travels of Aimee Schmidt: The Curse of the Gifted by J.A. Schreckenbach

Kit by Marina Fiorato

The Riviera Connection by John Creasey

Tango One by Stephen Leather

A Knife Edge by David Rollins

The Catherine Lim Collection by Catherine Lim

Five Classic Spenser Mysteries by Robert B. Parker

The Duke's Lady (Historical Romance - The Ladies Series) by Jernigan, Brenda

The Winter's Tale by William Shakespeare

Droit De Seigneur by Carolyn Faulkner