The Reenchantment of the World (12 page)

Read The Reenchantment of the World Online

Authors: Morris Berman

Plate 3. The alchemical androgyne. "Aurora consurgens," Ms. Rh 172,

Zentralbibliothek Zürich.

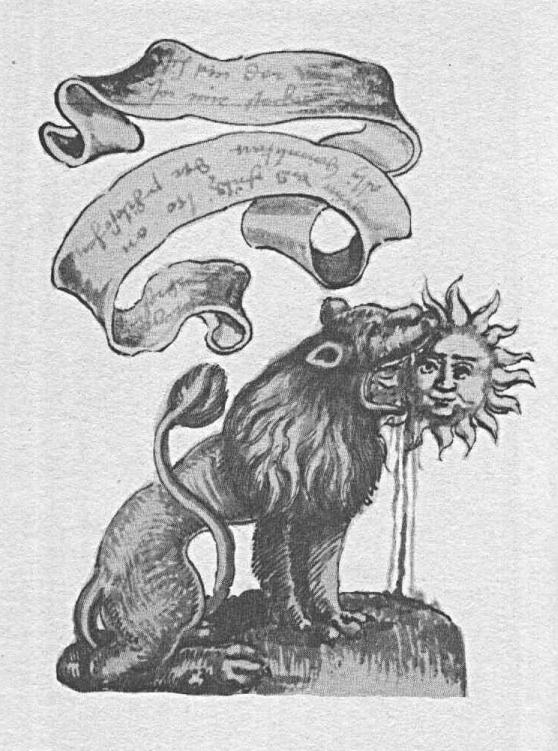

Plate 4. The green lion swallowing the sun. Arnold of Villanova,

"Rosariura philosophorum" (1550), Ms. 394a, f. 97, Kantonsbibliothek

(Vadiana), St. Gallen.

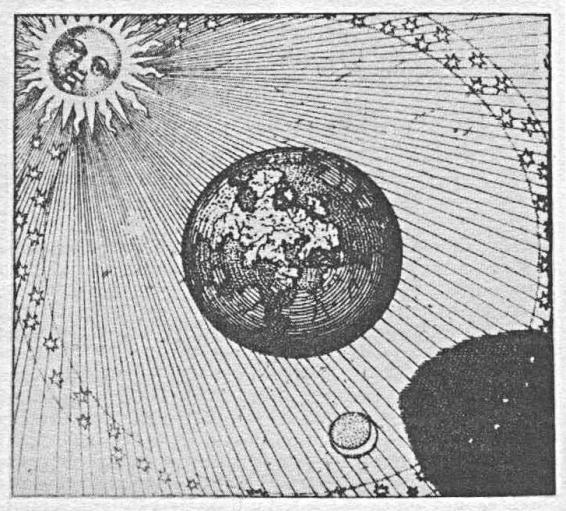

Plate 5. "Sol niger: the nigredo"; from J.D. Mylius, "Philosophia

reformata" (1622). Reproduced by C.G. Jung in Gesammelte Werke,

publ. Walter-Verlag.

that appears meaningless, and actually rather stupid, in its attempt to

rob significant images of their meaning. Thus, in the example given in

Chapter 1, if I dream that I am my father and that I am arguing with him,

it is irrelevant that this is not logically or empirically possible. What

is

relevant is that I awake from the dream in a cold sweat and remain

troubled for the rest of the day; that my psyche is in a state of civil

war, torn between what I want for myself and what my (introjected)

father wants for me. To the extent that this dilemma remains unresolved,

I shall be fragmented, un-whole; and since (Jung believed) the drive

for wholeness is inherent in the psyche, my unconscious will send out

dream after dream on this particular theme until I take steps to resolve

the conflict. And because life is dialectical, so too will be my dream

images. They will continue to violate the logical sequences of space and

time, and to represent opposing concepts that, on closer examination,

prove to be pretty much the same.

Plate 6. "The sun and his shadow complete the work," from Michael Maier,

"Scrutinium chymicum" (1687). Reproduced by C. G. Jung in "Gesammelte

Werke," publ. Walter-Verlag.

depth psychology, was the discovery that patients with no previous

knowledge of alchemy were having dreams that reproduced the imagery of

alchemical texts with a bewildering similarity. In his famous essay

"Individual Dream Symbolism in Relation to Alchemy," Jung recorded a

series of one such patient's dreams and produced for nearly every dream

a separate alchemical plate that duplicated the dream symbols in an

unmistakable way.19 Inasmuch as Jung claimed that others had produced a

similar set of dream images while undergoing the individuation process,

Jung was forced to conclude that this process was indeed inherent in the

psyche and that the alchemists, without really knowing exactly what they

were doing, had recorded the transformations of their own unconscious

which they then projected onto the material world. The gold of which

they spoke was thus not really gold, but a "golden" state of mind,

the altered state of consciousness which overwhelms the person in an

experience such as the Zen satori or the God-experience recorded by such

Western mystics as Jacob Boehme (himself an alchemist), St. John of the

Cross, or St. Theresa of Avila. Far from being some pseudo-science or

protochemistry, then, alchemy was fully real -- the last major synthetic

iconography of the human unconscious in the West. Or, in Norman O. Brown's

terms, "the last effort of Western man to produce a science based on an

erotic sense of reality."20

repression of the unconscious characteristic of the West since the

Scientific Revolution -- a repression that he saw as having tragic

consequences in the modern era, including widespread mental illness

and orgies of genocide and barbarism.21 Thus Jung believed that

the failure of each individual to confront his own psychic demons,

the part of his personality he hated and feared (what Jung called the

"shadow"), inevitably had disastrous consequences; and that the only

hope, at least on the individual level, was to undertake the psychic

journey that was in fact the essence of alchemy. In the cryptic words

of the seventeenth-century alchemist and Rosicrucian, Michael Maier:

'The sun and his shadow complete the work' (see Plate 6).22 The creation

of the Self lies not in repressing the unconscious, but in reintroducing

it to the conscious mind.

in alchemical texts suddenly made sense. The "Ourobouros" of Plate 2,

for example, a symbol that occurs (in one form or another) in almost

every culture, represents the achievement of psychic integration,

the unification of opposites. Green is the color of an early stage of

the alchemical process, whereas red (the 'rubedo,' as it was called)

is that of a later one. Hence beginning and end, head and tail, alpha

and omega, are united. The gold, or the Self, inherent from the first,

is finally separated out. The world is the same, but the person has

changed. As T. S. Eliot put it in "Little Gidding":

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

resemblance, was captured in alchemy by pictures of androgynes (Plate

3), hermaphrodites, and brother-sister marriages or sexual unions. The

conjunction of opposites occurs in the alchemical alembic, where lead

is seen to be gold in potentia, where mercury is both liquid and metal,

where what is volatile (represented by the rising eagle) becomes fixed,

and what is fixed (the dead eagles at the bottom) volatile.

lion attempting to eat or swallow the sun. As already indicated, green

is an early stage of the process, where the raw, vegetative force of the

unconscious is released and the conscious mind feels itself in danger of

being devoured. The alchemical slogan, "Do not use high-grade fires,"

is appropriate here. The cycle of sublimation and distillation is slow

and infinitely tedious, as are all the alchemical operations, and any

attempt to hasten the process will only prove abortive. The danger in

tapping the unconscious is that one will get more than one bargained for;

that the repressed unconscious will overwhelm the conscious as a hole

is poked in the dike separating the two. This phenomenon is well known

to many psychiatrists, as well as to many people who have studied yoga,

meditation, or have experimented with psychedelic drugs ("high-grade

fires").23 The person in search of integration may be permanenently

scared off, or forced to undertake his or her search from the very

beginning. At the very worst, the eruption of unconscious information

can dismember the soul, result in psychosis.24 The alchemical process is

often summed up in the phrase 'solve et coagula'; the persona is dissolved

(on the psychic level) so as to enable the real Self to coagulate, or come

together. But as R.D. Laing points out in "The Politics of Experience,"

there is no guarantee that this Self will coagulate; indeed, such a

result may be especially unlikely in a culture that is terrified of the

unconscious and rushes to drug the individual back into what it defines

as reality.25 Even the relatively alchemical culture of the Middle Ages

was keenly aware of such danger, as Plate 4 indicates; and it was part

of the alchemical opus to "tame" the green lion, or

"cut off his paws" -- an act that (in material terms, from our

point of view) consisted in touching sulfur with mercury or boiling

it in acid for an entire day. If this taming were not carried out,

the breakthrough of the unconscious, the dissolution of the ego, the

collapse of the subject/object distinction, the sudden conviction that

there is a Mind behind phenomenal appearances -- this single, unified

flash of light could catapult the practitioner into heaven or hell,

depending on his or her makeup and the particular circumstances. Hence

another crucial alchemical slogan: 'Nonnulli perierunt in opere nostro' --

"not a few have perished in our work."

in which the lead is dissolved and the solution becomes black. This

is the "dark night of the soul," the point at which the persona has

been dissolved and the Self has not yet appeared on the horizon. Hence

the skeleton, the death of the ego, and the black sun ('sol niger'),

representing acute depression. The "shadow" has now completely eclipsed

the conscious ego. In "The Divided Self," Laing quotes the writing of

a schizophrenic patient who, with no previous knowledge of alchemy,

uses the phrase "black sun" to describe her way of experiencing the

world. But in dialectical fashion, lead contains the nugget of gold,

and the skilled alchemist can bring about the transmutation by careful

attention to his experiments. Hence the concluding line of Laing's book:

"If one could go deep into the depth of the dark earth one would discover

'the bright gold,' or if one could get fathoms down one would discover

'the pearl at the bottom of the sea.' "26

evidence that the alchemists were quite deliberate about the psychic

aspect of their work. 'Aurum nostrum non est aurum vulgi,' they write;

"our gold is not the common [i.e., commercial] gold." 'Tam ethice quam

physice'; "as much moral as material." Or as one alchemist, Gerhard

Dorn, candidly put it: "Transform yourselves into living philosophical

stones!" Thus Jung was able to claim that what was "really" taking place

in the alchemist's laboratory was the psychic process of self-realization,

which was, then projected onto the contents of the furnace or alembic. The

alchemist

thought

he made gold, but of course he didn't; rather, he

made some concoction that, due to his altered state of consciousness,

he called "gold."

in the course of their work alchemists practiced a number of techniques

that can produce these altered psychic states: meditation, fasting, yogic

or "embryonic" breathing, and sometimes the chanting of mantras. These

techniques have been practiced for millennia, especially in Asia, for

the express purpose (in our terms) of breaking down the divide between

the conscious and unconscious parts of the mind. They strip the person of

mundane desires, enabling him to penetrate another dimension of reality;

and as Western science is just beginning to discover, they are certainly

efficacious in physiological terms, especially if we adopt the (to me,

quite reasonable) position that soul is another name for what the body

does. It is easy to assume that the psychic aspect is the reality,

and the material aspect deluded or irrelevant.

Other books

My Soul to Keep by Carolyn McCray

A Stone's Throw (The Gryphonpike Chronicles Book 3) by Annie Bellet

Passions of War by Hilary Green

United Eden by Nicole Williams

Ten Little Aliens: 50th Anniversary Edition by Stephen Cole

The Methuselah Project by Rick Barry

Dark Parties by Sara Grant

Uninvited: An Unloved Ones Prequel #2 (The Unloved Ones Prequels) by Richey, Kevin

Christmas Delights 3 by RJ Scott, Kay Berrisford, Valynda King,

Reversed by Alexa Grave