The Reenchantment of the World (14 page)

Read The Reenchantment of the World Online

Authors: Morris Berman

most readers as radical in the extreme. The above analysis forces me to

conclude that it is not merely the case that men conceived of matter as

possessing mind in those days, but rather that in those days, matter

did

possess mind, "actually" did so. When the obvious objection is raised

that the mechanical world view must be true, because we are in fact

able to send a man to the moon or invent technologies that demonstrably

work, I can only reply that the animistic world view, which lasted for

millennia, was also fully efficacious to its believers. In other words,

our ancestors constructed reality in a way that typically produced

verifiable results, and this is why Jung's theory of projection is off

the mark. If another break in consciousness of the same magnitude as

that represented by the Scientific Revolution were to occur, those on

the other side of that watershed might conclude that our epistemology

somehow "projected" mechanism onto nature. But modern science, with

the significant exception of quantum mechanics, does not regard the

gestalt of matter/motion/experiment/quantification as a

metaphor

for reality; it regards it as the

touchstone

of reality. And if the

criterion is going to be efficacy, we can only note that our own world

view has pragmatic anomalies that are as extensive as those of either

the magical or the Aristotelian world view. We are not, for example,

able to explain psychokinesis, ESP, psychic healing, or a host of other

"paranormal" phenomena by means of the current paradigm. There is no way,

on a pragmatic basis, to make a judgment in terms of any epistemological

superiority, and in fact, in terms of providing for a comprehensible

world, original participation might even win out. Participation

constitutes an insuperable historical barrier unless we consent to

regenerate a dead evolutionary pattern -- an act that would return us to a

world view in which it would be meaningless to ask: Which epistemology is

superior? Regenerating this pattern, we would, in some important sense,

have fallen back through the rabbit hole whence we originally came. In

such a world, the material transformation of lead to gold may well occur,

but we cannot know that now, nor can we know it for the Middle Ages.

exposed. Most historical and anthropological studies of witchcraft, for

example, never speculate that the massive number of witchcraft trials

during the sixteenth century might have been caused by something more than

mass hysteria. (Will our descendants, we wonder, regard our involvement

with science and technology as mass hysteria, or more correctly realize

that it was a way of life?) The number of works that depict participating

consciousness from the inside, such as Chinua Achebe's description of

Nigerian village life in "Things Fall Apart," is very small indeed; and

I know of only one writer who has managed both to enter that world and

to articulate its epistemology in modern terms -- Carlos Castaneda.34 I

shall be discussing alternative realities in greater detail later on in

this book. For now, the reader should be aware of how stark the choice

really is. Either such realities were mass hallucinations that went on

for centuries, or they were indeed realities, although not commensurable

with our own. In his critique of Castaneda's work, anthropologist Paul

Riesman confronts the issue directly, though the reader should note that

Riesman hardly represents mainstream thinking on the subject:

knowledge of other peoples as forms and structures necessary for

human life that those people have developed and imposed upon a reality

which we know -- or at least our scientists know -- better than they

do. We can therefore study those forms in relation to "reality" and

measure how well or ill they are adapted to it. In their studies

of the cultures of other people, even those anthropologists who

sincerely love the people they study almost never think that they

are learning something about the way the world really is. Rather,

they conceive of themselves as finding out what other people's

conceptions

of the world are.35

general, we have made precisely this mistake. We seek to describe what

the alchemist

thought

he was up to; we never grasp that what he was

"actually" doing was real. Moreover, we rarely apply this methodology to

our own methodology; we never manage to see

our

culture and knowledge as

"forms and structures necessary for human life" as it exists in Western

industrial societies.

judge them in our terms. The price paid, however, is that what we

actually learn about them is severely limited before the inquiry even

begins. Nonparticipating consciousness cannot "see" participating

consciousness any more than Cartesian analysis can "see" artistic

beauty. Perhaps Heraclitus put it best in the sixth century B.C. when

he wrote, "What is divine escapes men's notice because of their

incredulity."36

is especially relevant because of the role of values in shaping our

perceptions. Our purpose with respect to gold is not very different

from that of King Midas. We seek to know how the alchemist "did

it". because we see gold as a vehicle for obtaining other things. To

the true alchemist, gold was the end, not the means. The manufacture of

gold was the culmination of his own long spiritual evolution, and this

was the reason for his silence. "The material aim of the alchemists,"

writes the historian Sherwood Taylor,

and the alchemical vessel is the uranium pile. Its success has had

precisely the result that the alchemists feared and guarded against,

the placing of gigantic power in the hands of those who have not been

fitted by spiritual training to receive it. If science, philosophy,

and religion had remained associated as they were in alchemy, we

might not today be confronted with this fearful problem.37

world view, or driven underground to become part of the ideology of

so-called obscurantist groups: Rosicrucians, Freemasons, and others. In

terms of making a claim on the dominant culture, its last great stand

occurred during the English Civil War and Commonwealth period (1642-60),

and its last great practitioner was Isaac Newton, though he wisely kept it

a private matter.38 Yet because alchemy (and all of the occult sciences)

represents a map of the unconscious, because it apparently corresponds

to a psychic substrate that is trans-historical, alchemy is still with

us, both privately and publicly, and it is doubtful that dialectical

reason can ever be completely extirpated. Privately it survives, as we

have seen, in dreams, and also in psychosis.39 Publicly it has but one

surviving domain -- the world of surrealist art. The express purpose

of the Surrealist Movement in the first half of the twentieth century

was to free men and women by liberating the images of the unconscious,

by deliberately making such images conscious. There is, as a result, a

peculiar visual link between alchemical plates, dreams, and surrealist

art which seems to go deeper than appearances. All three use allegory

and the incongruous juxtaposition of objects, and all three violate

the principles of scientific causality and noncontradiction. Yet they

do create a message by somehow managing to reflect, or evoke, certain

familiar states of mind. These messages are intuitive, even numinous,

rather than cognitive-rational, but we somehow "know" what they are

saying. Their rules are those of premodern logic, of participating

consciousness, of resemblance and "a secret affinity between certain

images." "One cannot speak about mystery," wrote René Magritte; "one

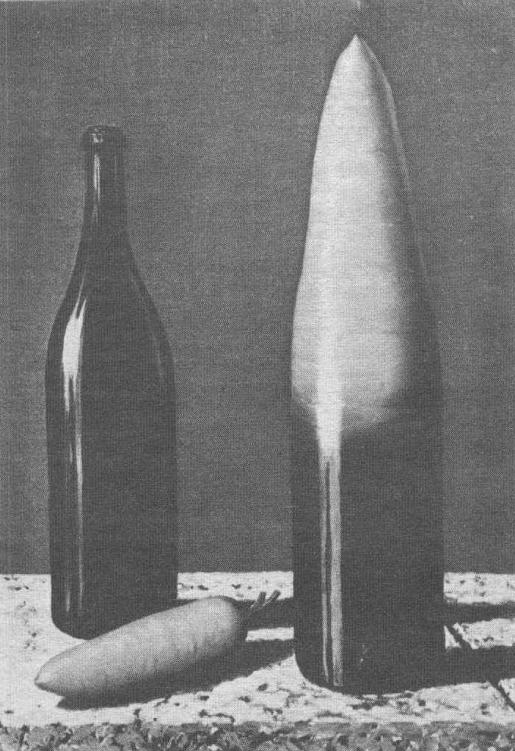

must be seized by it.40 Hence the highly alchemical nature of a painting

like 'The Explanation' (Plate 7), in which a carrot anda bottle are both

reasonably seen as distinct, and no less reasonably fused into a single

object. Salvador Dali's 'The Persistence of Memory' (Plate 8) has the

same dreamlike quality, in which linear, mechanical time has started

to wilt and run down in the arid desert of the twentieth century. Both

of these paintings employ the same sort of logic and imagery that we

observed in Plates 2 - 6.

in the twentieth century could possibly mean later on in this work. Our

task now, however, is to try to solve the puzzle of why it was ever

lost in the first place. Although we may have succeeded in immersing

ourselves in that world view, we have not yet addressed the question of

how modern science managed to refute it. The holistic framework of the

occult sciences lasted for millennia, but it took Western Europe a mere

two hundred years -- roughly between 1500 and 1700 -- to break it apart,

revealing that the Hermetic tradition was, despite its long tenure,

rather fragile.

dualistic nature. Magic was at once spiritual and manipulative, or,

in D.P. Walkers terminology, subjective and transitive.41 Each of the

occult sciences, including alchemy, astrology, and the cabala, aimed

at both the acquisition of practical, mundane objectives, and union

with the Divinity. There was always a tension between these two goals

(which is not the same thing as an antagonism) because they constituted

a rather delicate ecological framework. If, for example, I am acting as

a "midwife" to nature, accelerating its tempo in altering the nature of

matter, it is clear that I am interfering in its natural rhythm. Any type

of human action upon the environment can be seen in these terms. But the

point is that the interference was always consciously acknowledged. It

was sanctified through ritual, lest the earth strike back against man

for this incursion into its womb. This interference was performed in

the context of a mentality, and an economy (steady-state), that sought

harmony with nature, and in which the notion of mastery of nature

would have been regarded as a contradiction in terms. Nevertheless,

the distinction ultimately involved a difference of degree rather than

kind, for at what point in our acceleration of nature's tempo can we be

said to have crossed the line from midwifery to induced birth, or even

abortion? What degree of interference tips the balance from harmony to

attempted mastery? In a feudal context of subsistence economy and only

moderately diffused technology, in a religious context that regarded

nature as alive and our relationship to it as one of participation, it

was very difficult for such a question to arise, and in this sense the

alchemical tradition was not all that fragile. But with the social and

economic changes wrought in the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries, the sacred and the manipulative were split down the middle. The

latter could easily survive in a context of profit, expanding technology,

and secular salvation; indeed, that was what the manipulative aspect was

all about, severed from its religious basis. Thus Eliade rightly calls

modern science the secular version of the alchemists dream, for latent

within the dream is "the pathetic programme of the industrial societies

whose aim is the total transmutation of Nature, its transformation into

'energy.'"42 The sacred aspect of the art became, for the dominant

culture, ineffective and ultimately meaningless. In other words, the

domination of nature always lurked as a possibility within the Hermetic

tradition, but was not seen as separable from its esoteric framework

until the Renaissance. in that eventual separation lay the world view

of modernity: the technological, or the 'zweckrational,' as a logos.

Plate 7. René Magritte, "The Explanation" (1952). Copyright ©

by A.D.A.G.P., Paris, 1981.

Plate 8. Salvador Dali, "The Persistence of Memory (1931), oil on canvas,

9-1/2" x 13". Collection, The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

could actually have served as a matrix for the Scientific Revolution. As

explained in Chapter 2, technology had no theoretical or ideological

basis, at least not until Francis Bacon. Even down to the time of Leonardo

da Vinci, machines tended to be seen as toys, whereas the concept

of force was linked to the Hermetic theme of universal animation.43

Technology, in short, could not be a rival to Aristotelianism because

it was not a

Other books

The Road to Compiegne by Jean Plaidy

Hitler's War by Harry Turtledove

I Am the Chosen King by Helen Hollick

Rock 'n' Roll is Undead (Veronica Mason by Pressey Rose

Craddock by Finch, Paul, Neil Jackson

Timing by Mary Calmes

Great Historical Novels by Fay Weldon

His by Valentine's Day by Starla Kaye