The Ride of My Life (14 page)

The cover photo from

Go

was also the cover of a video. After France, Eddie Roman came out to visit and we filmed

Head First

, another home-brewed Roman production. The action opened with Eddie posing as a kitchen appliance and basically eating garbage, regurgitating it, and then feeding the mixture to his friend. This was the first video to feature excessive coverage of street and mini-ramp riding, which were becoming all the rage in the sport. I also rode a lot of dirt jumps. I was riding for Haro but was going through a bike a day while we compiled footage. My bikes change color every other scene, and after some tricks, parts can be seen literally breaking off my bike. While making Head

First

, I adapted the art of big handrails from skateboarding to bikes. I pulled a burly twenty-two stepper while filming with Eddie in downtown Oklahoma City.

It was fun documenting and progressing my riding, but even as I reached new highs, some dark clouds were blowing into the freestyle scene as the 1980s drew to a close. Most riders didn’t seem to question it, or didn’t want to acknowledge what was coming. But if you read the writing on the wall, it was apparent things were going to get worse before they got better. A lot of manufacturers who had jumped on the bandwagon in the early 1980s to cash in on the sport were filing for bankruptcy or focusing their business efforts elsewhere. Green grips, turquoise tires, pink pegs, and other novelty colored bolt-on components began to collect dust in bike shops. Sales also flatlined for cheap line extension freestyle bicycles pumped out by corporate giants like Murray, General, and Schwinn. Some attributed this to the fact that riders were just getting smarter and knew what worked and what didn’t. Of course, there were other signs, too. At one point in the mideighties, six different monthly freestyle magazines were on newsstands in the United States; these too began to fall like leaves from a tree.

As the bike industry recession began to take root, there were plenty of theories about why freestyle was ailing. It was reasoned that the kids who, a few years prior, got freestyle bikes when they were fourteen or fifteen years old had grown up, gone to college, or joined the workforce, leaving trick riding behind. A new crop would need to grow and take their place. In the meantime, the bike industry was shifting gears, riding the momentum as mountain bikes got hot. Companies responded by diverting dollars and energy into the new savior/flavor of the month, which resulted in budgets slashed from their hemorrhaging freestyle programs. In some cases, entire freestyle teams disappeared from the contest and touring circuit.

The riders themselves were also partially responsible for bringing about change. As bikers, we had evolved out of our BMX ancestry and were creating our own culture and identity. Street riding came up fast and dirty; it was jarring, often illegal, and you looked totally stupid doing it wearing stuffy nylon BMX-style pants and a long-sleeved jersey. Street fever brought with it new attitude, and it made the bike industry conservatives nervous. What was once a well-behaved golden child had become a sweaty, bloody, public-property-destroying rebellious teenager wearing a new uniform of ripped shorts and a T-shirt with a giant anarchy symbol emblazoned on the front.

As the reins were tightened and income potential evaporated, those who were in it for the money left bikes to pursue other dreams. I quit Haro and began to pay my own expenses to get to contests. Pretty quickly I realized I needed to figure out where I wanted to go with my career. Nobody was going to hold my hand and lead the way. My first concern was to make sure my riding was pro caliber.

Being my own sponsor meant I had to pay for everything myself, and sometimes it was tight. I won $950 at the next KOV contest, held in New York City. My victory check was the only money I had to finance my trip and to live on. Dennis McCoy and I couldn’t find a hotel in our price range, so we did a little urban camping in the streets of Manhattan. While I slept, Dennis stole the check from my hip sack. I was rousted in the early morning hours by a belligerent wino, who was pissed off that I was occupying his special spot. After wiping the sleep from my eyes, I realized my wallet was about a grand lighter. I looked all over for my check, asking everyone I knew if they’d seen it. No one had, so I accepted the money was gone. Dennis savored my distress for another five hours, until we got to the airport, where he finally broke down and started laughing. He handed me my check, and I thanked him with a good sock in the arm.

You’re a real kidder, McCoy

. The worst part about the New York KOV contest: It was the last one Mike Dominguez ever entered. He slammed hard on a 900 and bloodied his face and jacked up his wrist. It was a definite downer to see him go.

This was the first flair I did. Announcer Kevin Martin jumped in the air and landed straight on his knees after I pulled it. He got more injured than I did. (Photograph courtesy of Mark Noble)

KEEP ON TRUCKIN’

Even with my contest winnings, it was tough supporting myself. The louder the bike industry blowhards declared freestyle was dying, the more I vowed to be the cure. I wanted to help turn on new kids to riding. The key to finding a new generation of riders was to seek out places where there were lots of people and show them what was possible on a bike. To make it happen, I became four different people: business owner, trucker, athlete, and carnival attraction.

Open highway, big wheel of the Peterbuilt in my hand…life is good.

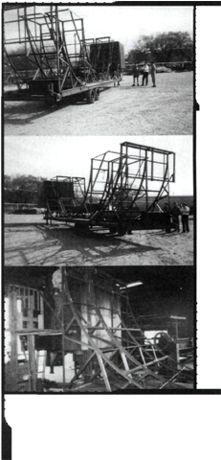

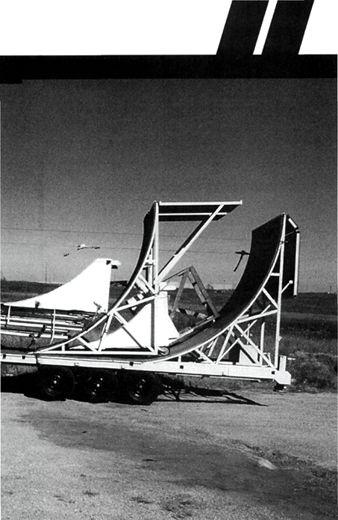

I went into business with my dad, my old tour manager Ron Haro, and Dennis McCoy. We formed a company called VIP Concepts, and our goal was to shoot for the big time, doing bike demos at major events. Dennis and I would be traveling performers, like a rock band. The first order of business was to get together a rig. The age of the quarterpipe was over. And frankly, quarterpipes were getting dangerous to ride, because the level of tricks was getting so out of hand. It was time to evolve. We wanted to have the first halfpipe freestyle show. Halfpipes kept the action flowing smoothly and were perfect for a demo, but nobody had ever tried making a portable one. We commissioned a custom-built, portable halfpipe from a local welding wizard. After the ramp and trailer were done, we needed a truck to haul it, and bought a C-60 class truck, a big commercial-grade vehicle that runs on gasoline instead of diesel fuel.

We landed a few gigs doing demos at fairs, festivals, and amusement parks. It was a rocky start, but slowly we began breaking into the business. My dad and Ron Haro had helped get VIP started with their business wisdom, but they didn’t have the connections to get us into the glamorous world of rock-concert-level production and promotion. Our operation was losing money. I bought out the equipment from my partners with the last of the cash in my bank account, and we shut down VIP. The way I look at it: If you’re going to fail, the best thing you can do is fail fast and learn from your mistakes. I prepared for my next business venture with the help of my accomplice, Steve Swope. But first we needed to make few adjustments.

A posse of us were out street riding in downtown Oklahoma City one night when we met a babbling genius. From behind his crusty shopping cart he called us a pack of “Sprocket Jockeys.” The name was perfect. We thanked him for his concept and treated him to some free entertainment. Then I enlisted the aid of another consultant, a bike rider named Brian Scura, who I thought could help us break further into the state fair demo circuit.

Rick Thorne and I dorkin’ in Deer Creek. The Sprocket Jockeys were regulars at the Deer Creek fair in Indianapolis.

The original Sprocket Jockeys rig.

Scura was from a different school of freestyle. He’d been around the bike industry forever and had a ton of success as the inventor of the Gyro, a device that kept brake cables from tangling while allowing the handlebars to spin freely. Scura was also, to his credit, over the age of thirty and still riding. Or I should say, still performing. His forte was doing demos: elementary schools, fairs, petting zoos, the grand opening of a donut shop—you name it, he’d ride it for crowds. I wanted to get the booking and promotional knowledge out of his head and into mine. This would be a test of patience, however.

We both had our own ideas about what a freestyle show should consist of. Scura was fond of wearing BMX pants with a nylon jersey that was printed up like a fake tuxedo. A white tuxedo, with custom tails. It was rumored he even wore a top hat. For a good portion of his shows he rode around on a special one-trick-bicycle dubbed the wheelie machine. He did choreographed performances that included lots of ground tricks, dancing, audience participation, blatant hand-clapping, lip synching to pop music tunes, and air guitar. He even wrote new lyrics and overdubbed them to songs like “Johnny B. Goode” or “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” to make the songs reflect his deeds on a bike. Granted, his young audiences ate it up. But that showmanship-centric approach to demos just wasn’t me.

Scura wanted to, in his own words, “manage the H-E-double-toothpicks out of the Sprocket Jockeys.” He invited me to join him at a trade show dedicated to the carnival, state fair, and amusement park industry, to show me the ropes and discuss a rider/manager business arrangement. I flew to California for the trade show. Scura took one look at my style of worn-out jeans, Club Homeboy T-shirt, and long hair and said we couldn’t go in the convention center until I had a makeover. He took me to a Chess King store in a local mall and bought me a crew-knit golf shirt and some other fancy duds. He also got me a hat, alluding to the fact that I’d need to cover my hair, which I was growing out.