Read The Rise of Rome: The Making of the World's Greatest Empire Online

Authors: Anthony Everitt

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

The Rise of Rome: The Making of the World's Greatest Empire (57 page)

Caesar did much better. He spent ten years conquering the Celtic

tribes of Gaul, showing himself to be as brilliant in the field as he was in the Forum. He only returned to domestic politics in 50. He intended to stand for the consulship again, but the Senate blocked him on an electoral technicality. So Caesar led his legions across a little stream called the Rubicon, which marked the frontier between the province of Cisalpine Gaul and Italy itself. “The dice have been thrown,” he remarked dryly. The Senate won Pompey to its side and fought back, but Caesar defeated his old partner in a great battle at Pharsalus, in central Greece. Pompey fled to Egypt, where the nervous authorities had him killed.

By 45, the war was over and Caesar was master of the Roman world. He did not intend to repeat Sulla’s mistake and retire early. He appointed himself dictator for life. This was tantamount to being king, the unforgivable crime. On the Ides of March in 44

B.C

., during a meeting of the Senate, he was stabbed to death by angry aristocrats. He collapsed at the feet of a statue of Pompey the Great.

Another fourteen years were to pass before peace returned to the empire. Caesar’s adoptive son, Octavian, an inexperienced but clever eighteen-year-old, and Mark Antony, an able but idle military commander who had been one of Caesar’s henchmen, launched a Proscription as savage as that of Sulla. After defeating Caesar’s assassins at Philippi, they divided the empire between them. Octavian took the West and Antony the East. As far as they were concerned, the Republic was dead. They, too, then fell out, however. Another civil war ensued, which Octavian won at the sea battle of Actium.

In 27, with breathtaking dexterity, he brought back the Republic—but in name only. Renamed Augustus, the Revered One, he restored elections, and political life seemed to return to normal. However, he made sure to maintain control over the legions, and he was given a tribune’s powers regularly renewed—the veto, authority to table laws, personal inviolability—but without

the tiresome obligation of actually having to hold the office. The ruling class, decimated in the wars, accepted the pretense.

A little more than one hundred years had passed since the tribuneship of Tiberius Gracchus and almost exactly fifty years since the reign of Sulla, the

Sullanum regnum

. Like the inexorable plot of a Greek tragedy, the consequences of the constitutional breakdown they brought about had finally worked themselves out.

18

Afterword

I

T HAS OFTEN BEEN SAID THAT HISTORY IS WRITTEN

by the victors, but in the case of Rome it was the losers who commandeered the narrative. Even those who published under the severe gaze of the emperors looked back on the Roman Republic with respect and nostalgia. For this, Cicero and Varro can take much of the credit. They committed scholarly errors and misjudgments, but, like a sacred flame, they preserved the spirit of the Republic that was dying.

They were political failures. Enemies of Julius Caesar, they witnessed the destruction of all their hopes. Varro made his peace with the great dictator, won over by a commission to establish Rome’s first public library; he died in his bed at the ripe age of eighty-nine. Cicero was made of sterner stuff. After the Ides of March, he bravely returned to politics. He tried to save the Republic, but fell victim to Octavian and Mark Antony’s Proscription.

As authors, though, the two friends excelled. Their rural retirement was not wasted. They wrote much on the rise of Rome, excavating and analyzing the past as best they could. Cicero said of Varro:

We were wandering and straying about like strangers in our own city, and your books led us, so to speak, right home, and enabled

us at last to realize who and where we were. You have revealed the age of our native city, the chronology of its history, the laws of its religion, its civil and military institutions, the topography of its districts and sites … and you have likewise shed a flood of light upon our poets and generally on Latin literature and the Latin language.

Cicero was less of a scholar than Varro and more of a controversialist. He noted: “

Like the learned men of old, we must serve the state in our libraries, if we cannot do so in the Senate or the Forum, and pursue our researches into custom and law.” His main contributions were

Republic

and

Laws

, two substantial tomes in which he examined the history of the Roman constitution and, while allowing for reforms, commended its virtues. A moderate conservative, he believed that “

excessive liberty leads both nations and individuals into excessive slavery.”

Cicero had sharp eyes, and it seems strange that his books do not offer a more accurate perception of what was really happening. The explanation is that, like most of his contemporaries, he saw politics fundamentally in personal rather than ideological or structural terms. There had been a decline in moral standards in public life. All would be well if only there was a return to traditional values, to the

mos maiorum

. Caesar disagreed. With the insight of genius, he saw that incremental reforms would not save the day, nor would a return to the ideals of Cincinnatus. An altogether new system of government was required.

Grief-stricken by his daughter’s death in 45, Cicero went on to write a series of books that presented Greek philosophy to Latin readers. They form the basis of his reputation with posterity and, in the past two millennia, empowered the thinking of generations of European readers.

Cicero regarded Julius Caesar as a second Hannibal, but though the dictator manipulated and bullied him as a politician, he held

Cicero in the highest esteem as an author. He once wrote of him that he was “

winner of a greater laurel wreath than any gained by a triumph, insomuch as it is greater to have advanced the frontiers of Roman genius than those of the Roman empire.”

Praise from one’s worst enemy is the most annoying, but also the most credible, of compliments.

SO THE LONG

, slow collapse of the Roman Republic had one positive consequence. The uncertainties of the age impelled men like Cicero and Varro to inquire into their collective past—to find an explanation for the crisis and, as a kind of antidote, to reveal the basis of their country’s vanishing greatness. They evoked an idea of Rome that still lives and breathes two thousand years later.

But what was gone was gone, and they knew that. Cicero wrote the epitaph:

The Republic, when it was handed down to us, was like a beautiful painting, whose colors were already fading with age. Our own time has not only neglected to freshen it by renewing its original colors, but has not even gone to the trouble of preserving its design and portrayal of figures.

THE WOLF

If ancient Rome were to have a logo, it would be this bronze wolf, ferocious and tender, that suckled the babies Romulus and Remus, who as young men went on to found the city of Rome. The wolf is traditionally believed to be of Etruscan make, dating from the fifth century (although some scholars argue that it is medieval). The infants were added by the Renaissance artist Antonio Pollaiuolo.

Capitoline Museums, Rome

THE GREAT DAYS OF OLD

There are no original images of Rome’s early history. The French revolutionary painter Jacques-Louis David admired the legendary stories of austere patriotism and created his own versions, which are close in spirit to a Republican Roman’s worldview.

In his

Rape of the Sabine Women

, Hersilia, Romulus’s wife and daughter of his enemy Titus Tatius, rushes between the two men and halts a battle in the Forum between Romans and Sabines. She proposes that the Sabine women, whom the Romans have kidnapped, be given the chance to accept their forced marriages. This agreed, the union of the two peoples soon follows.

Louvre, Paris

In

The Oath of Horatii

, three brothers swear, in the presence of their father, to sacrifice their lives, if need be, in Rome’s war with the city of Alba Longa. With their unflinching gaze and taut limbs, they are the embodiment of noble valor. They go on to fight a ritual duel with three Alban counterparts, the brothers Curiatii, whom they kill. The women on the right remind us that one of their sisters is in love with a Curiatius. A brother puts her to death as punishment for her treasonable grief.

Louvre, Paris

THE RIVALS

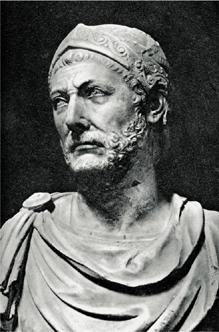

Hannibal was Rome’s greatest enemy and for a time brought it to its knees. This marble bust is reputed to be of the Carthaginian general and was found at the ancient city of Capua. If genuinely classical, it must surely have been carved after the defeat of his cause at the battle of Zama, for fierceness and focus are softened by melancholy and resignation.

Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples