The Road to Madness (2 page)

Read The Road to Madness Online

Authors: H.P. Lovecraft

The things that can be said about Howard Phillips Lovecraft don’t sum up, or even come close to summing up, what his writing is. On the down side, his writing is racist and sexist and wildly open to parody because it is so original, so idiosyncratic. (Some of his characters behave in a fashion that makes me want to knock them over the heads and yell, “Don’t go down into that cellar, you idiot!”)

But that isn’t the point.

I started reading Lovecraft when I was sixteen, and in many ways he was a major—perhaps

the

major—influence on my own writing. Every year or so I go on a Lovecraft binge, devouring story after story the way a glutton sits in a corner devouring cookies. Then I associate with those persons of more elevated tastes and feel a little ashamed of myself. But I meet the eyes of other Lovecraft addicts, and we smile.

Reading Lovecraft’s writing, one has the impression of a man so caught up in his vision that he is struggling to find language with which to share what he sees. Bizarre and elaborate words, piled atop one another in baroque cacophony, seem to be the only outlet he can find to convey the fulgent richness of his dream, to explain what is, at heart, inexplicable or at least incomprehensible: to name the nightmare.

To those of a certain temperament, that legion of my fellow addicts, H.P. Lovecraft’s tales are enormous fun.

Here we have a collection that combines some of his best tales with early or fragmentary works. In many of the lesser-known stories we find themes or images that recur in later or better-known works, stories played out from other angles but returning again and again to the same core nightmares. The takeover of one’s body by some entity of the past in “The Evil Clergyman” provides a foreshadowing of “The Thing on the Doorstep” and “Shadow Out of Time”; the history of rumors and secret cult activity stirring beneath the prosaic, if squalid, surface of an everyday slum that we find in “The Horror of Red Hook” mirrors the dark spine of the tale “The Shadow Over Innsmouth.”

Another theme found in “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” resurfaces in “Arthur Jermyn” and is one of Lovecraft’s most notable preoccupations: “bad blood” or evil or alien ancestry, forgotten for a time, that returns to destroy an innocent scion of the family.

Part of this, of course, is simply Lovecraft’s racism, the racism that until quite recently could strip a fair-skinned man or woman of civil rights and bar all entry into polite society, should it be discovered that one of their great-grandparents came from Africa; the racism that painted half the villains and thugs of his stories as “Negroes,” “lascars,” or “degenerates of horribly mixed race.” (And let’s not forget those “degenerate Eskimos” featured in “Call of Chthulu”!)

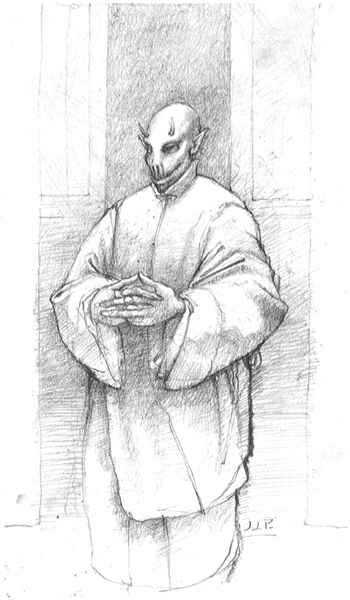

But the somber glee with which he traces the enormities of the tainted Jermyn line reflects also a delight with genealogy, with the history of families and the places that bear their stamp across the generations: the abominable de la Poers of Exham Priory, the gruesome descendants of Captain Marsh of Innsmouth. And indeed, Lovecraft’s villains were as likely to be Caucasians as anything else, degenerate or otherwise: men (at the moment I cannot think of a single Lovecraft story in which a woman was the linchpin of the plot’s evil—even Asenath Waite was actually a man) who delved for forbidden knowledge, acquired forbidden power, and surrendered their humanity in the process.

The image of the cursed family, the generational saga of evil, is a powerful one. And, as any fan of Romanov court histories or

Dynasty

can tell you, it’s powerful because it’s great, chewy fun.

As an historian, I cannot but revel in Lovecraft’s portrayal, again and again, of eldritch evil arising from the deeps of time. His thesis that humanity is but a blundering set of Johnny-come-lately peasants stumbling amid the terrible secrets of unknown Ancients opens the door to endless narrative possibilities. His catalog of forbidden lore—those yellowing fragments of parchment that the hero or the villain has to collate, the hideous volumes that it is not lawful even to possess—all bear wonderfully evocative titles: von Juntzt’s

Unaussprechlichen Kulten

, Ludvig Prinn’s

De Vermis Mysteriis

, and the unforgettable

Necronomicon

of the Mad Arab Abdul Alhazred. What bibliophile wouldn’t delight in displaying such things on his or her library shelves?

Lovecraft’s heroes and villains both tend to be scholars, treading the dangerous territory of forbidden knowledge, and many of Lovecraft’s greatest stories derive their tension from the scholarly unfolding of information, the coming to light of hidden records and hidden deeds.

I’m still not sure that any of this explains the fascination of Lovecraft, the power that his images and themes exert over so much of the literature of horror and the fantastic, over role-playing games and films both gruesome and comic (including the marvelously Lovecraftian

Ghostbusters

) sixty years after the man’s death.

But the influence is there. My fellow addicts are there. At a recent science fiction convention in Chicago nearly a thousand fans participated in a Lovecraftian role-playing game without anyone inquiring “Who?” (I was one of a dozen professionals slaughtered in eldritch and nameless circumstances, and it took all afternoon to get the fake blood out of my hair.) Lovecraft’s mythos is a standard part of the language of horror literature. Used bookstore owners tell me they can’t keep Lovecraft on the shelves.

Maybe it’s just that Lovecraft takes such obvious pleasure in what he writes. Enthusiasm is contagious. He was clearly a man who loved his craft.

This book, in many ways, is a progression, a journey. The stories serve as an illustration of H.P. Lovecraft’s progress from derivative pseudo-Poe, pseudo-Dunsany tales, some of them collaborations, to his own astonishing goals. In addition to the earlier fragments and stories, we see Lovecraft’s flights into less characteristic realms: “The White Ship” and “The Tree” are very much high fantasy; “The Shunned House” is a flat-out ghost story; “Cool Air,” one of my favorites, is a simple tale of gruesome horror, and “In the Walls of Eryx” is one of Lovecraft’s few excursions into outright science fiction. “Imprisoned With the Pharoahs,” aside from being a great deal of Indiana Jones-style fun, is interesting in that it purports to be written by escape artist and supernaturalist Harry Houdini, probably the only time Lovecraft wrote from the point of view of a real celebrity.

But from those early attempts and collaborations, and through the odd byways, we progress to his more mature, more confident, and more elaborate works, until like the unfortunate Professor Dyer, we arrive at last at the Mountains of Madness—classic Lovecraft, like a perfectly wrought black crystal—and find ourselves in strange and wondrous territory indeed.

These stories comprise a guidebook, then, to the lesser-known corners of the universe of shadows that was H.P. Lovecraft’s private vision of the world. Some of its nooks he only visited once. To others, he returned again and again, drawn by whatever it is that dwells in that darkness—as we all are drawn.

Early Tales

A

part from some inconsequential juvenilia written beginning when he was six years old, H. P. Lovecraft preserved only a few of what he called his early tales—that is, stories written in his teens and twenties—having destroyed most of them. These tales are manifestly early stories, uncertain and imperfect, written after a period during which he had put down little fiction

.

The earliest of these narratives dates back to Lovecraft’s fifteenth year, and presumably all but

The Transition of Juan Romero

were written when he was between fifteen and twenty

. The Transition of Juan Romero

was written when Lovecraft’s interest in fiction, some years dormant, was once more revived, and only a few years before he began to write the main body of his fiction

.

Since these early tales, particularly

The Beast in the Cave

and

The Alchemist,

show great promise, it is only to be speculated about whether that early promise would have been fulfilled sooner had Lovecraft’s fiction then earned the encouragement it merited. He lost here at least a decade of his creative life, when, discouraged in his late teens, he abandoned the writing of fiction almost until the advent of

Weird Tales.

The Beast in the Cave

T

he horrible conclusion which had been gradually obtruding itself upon my confused and reluctant mind was now an awful certainty. I was lost, completely, hopelessly lost in the vast and labyrinthine recess of the Mammoth Cave. Turn as I might, in no direction could my straining vision seize on any object capable of serving as a guide-post to set me on the outward path. That nevermore should I behold the blessed light of day, or scan the pleasant hills and dales of the beautiful world outside, my reason could no longer entertain the slightest unbelief. Hope had departed. Yet, indoctrinated as I was by a life of philosophical study, I derived no small measure of satisfaction from my unimpassioned demeanour; for although I had frequently read of the wild frenzies into which were thrown the victims of similar situation, I experienced none of these, but stood quiet as soon as I clearly realised the loss of my bearings.