The Road to Oxiana (8 page)

Read The Road to Oxiana Online

Authors: Robert Byron

The inn here is labelled “Grand HotelâTown Hall”. We have not been wholly dependent on it, since Hussein Mohammad Angorani, the local agent of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, invited us to supper. He received us in a long white room with a brilliantly painted ceiling; even the doors and windows were covered with white muslin. The furniture consisted of two brass bedsteads appointed with satin bolsters, and a ring of stiff settees, upholstered in white, before each of which stood a small white-covered table bearing dishes of melon, grapes, and sweets. In the middle of the floor, which was covered with two layers of carpets, stood three tall oil lamps, unshaded. A grey-bearded steward in a buff frock-coat, whom our host addressed as “aga”, attended us.

Our letter of introduction had said we wished to visit Sultaniya. If we returned this way, said our host, he would take us in his car. A trouble? He visited Sultaniya every day, for business or sport. In fact he had a house there, in which he could entertain us. In my innocence I believed these courtesies. But Christopher knew better. After an enormous meal, which we ate with our hands, the steward led us back to our bare cubicle in the Grand HotelâTown Hall.

I am sitting in the street outside it; for the morning sun is the only available warmth. A pompous old fellow in check tweeds, who looks like Lloyd George, has just

come up and announced himself as the Reis-i-Shosa. This means Captain of the Chaussées, in other words District Road Superintendent. He accompanied the English to Baku, where the reward of his help was a Bolshevik prison.

Tabriz

(4500

ft

.),

October 15th

.âIn Zinjan at last we picked up a lorry. As Christopher was taking a photograph of me sitting in the back, a policeman stepped up and said photographing was forbidden. The driver was an Assyrian from near Lake Urmiya, and by his side sat an Assyrian schoolmistress, who was returning from a missionary conference in Teheran. She regaled us with slices of quince. They were much interested in my acquaintance with Mar Shimun, and advised me to say nothing about it in Tabriz, since there was a persecution of Christians at the moment, and Mrs. Cochran's Women's Club in Urmiya had been shut by the police. At the thought of this, they sang

Lead

,

Kindly Light

in unison, the schoolmistress informing me that she had taught the driver this to prevent his singing the usual drivers' songs. I said I should have preferred the drivers' songs. She added that she had also persuaded him to remove the blue beads from his radiator-cap; they were a superstition of “these Moslems”. When I told her they were a superstition generally practised by Christians of the Orthodox Church, she was dumbfounded. She admitted then that superstitions sometimes worked: there was a devil named Mehmet, for instance, with a human wife, through whom he had prophesied the War in her father-in-law's parlour. She called herself a bible-worker, and wanted to know if most people in England smoked or did not smoke. Why doctors did not forbid smoking and drinking, instead of doing so themselves, she could not understand.

I began to sympathise with the Persian authorities.

Missionaries do noble work. But once they make converts, or find indigenous Christians, their usefulness is not so great.

Christopher, at this stage, was reading in the back of the lorry, where his companions were a Teherani, an Isfahani, two muleteers, and the driver's assistant.

Teherani

: What's this book?

Christopher

: A book of history.

Teherani

: What history?

Christopher

: The history of Rum and the countries near it, such as Persia, Egypt, Turkey, and Frankistan.

Assistant

(

opening the book

): Ya Ali! What characters!

Teherani

: Can you read it?

Christopher

: Of course. It's my language.

Teherani

: Read it to us.

Christopher

: But you cannot understand the language.

Isfahani

: No matter. Read a little.

Muleteers

: Go on! Go on!

Christopher

: “It may occasion some surprise that the Roman pontiff should erect, in the heart of France, the tribunal from whence he hurled his anathemas against the king; but our surprise will vanish so soon as we form a just estimate of a king of France in the eleventh century.”

Teherani

: What's that about?

Christopher

: About the Pope.

Teherani

: The Foof? Who's that?

Christopher

: The Caliph of Rum.

Muleteer

: It's a history of the Caliph of Rum.

Teherani

: Shut up! Is it a new book?

Assistant

: Is it full of clean thoughts?

Christopher

: It is without religion. The man who wrote it did not believe in the prophets.

Teherani

: Did he believe in God?

Christopher

: Perhaps. But he despised the prophets. He

said that Jesus was an ordinary man (

general agreement

) and that Mohammad was an ordinary man (

general depression

) and that Zoroaster was an ordinary man.

Muleteer

(

who speaks Turkish and doesn't understand well

): Was he called Zoroaster?

Christopher

: No, Gibbon.

Chorus

: Ghiboon! Ghiboon!

Teherani

: Is there any religion which says there is no god?

Christopher

: I think not. But in Africa they worship idols.

Teherani

: Are there many idolaters in England?

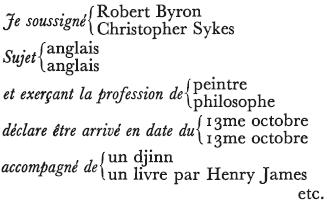

The road led into mountains, where a great gorge brought us to the river of the Golden Swimmer. He was a shepherd, a Leander, who used to swim across to visit his beloved, until at last she built the truly magnificent bridge by which we also crossed. A herd of gazelle frisked along beside us. At length we came out on the Azerbaijan highlands, a dun sweeping country like Spain in winter. We passed through Miana, which is famous for a bug that bites only strangers, and spent the night in a lonely caravanserai where a wolf was tethered in the courtyard. At Tabriz the police asked us for five photographs each (they did not get them) and the following information:

AVIS

The features of Tabriz are a view of plush-coloured mountains, approached by lemon-coloured foothills; a drinkable white wine and a disgusting beer; several miles of superb brick-vaulted bazaars; and a new municipal garden containing a bronze statue of Marjoribanks in a cloak. There are two monuments: the wreck of the famous Blue Mosque, veneered in XVth-century mosaic; and the Ark, or Citadel, a mountain of small russet bricks laid with consummate art, which looks as if it had once been a mosque, and if so, one of the biggest ever built. Turkish is the only language, except among officials. The merchants were formerly prosperous, but have been ruined by Marjoribanks's belief in a planned economy.

Maragha

(4900

ft

.),

October 16th

.âWe drove here this morning in four hours, through country that reminded me of Donegal. Lake Urmiya appeared in the distance, a streak of blue and silver, with mountains beyond. Square pigeon-towers, perforated at the top, gave the villages a fortified appearance. Round about were vineyards, and groves of

sanjuk

1

trees, which have narrow grey leaves and clusters of small yellow fruit.

Maragha itself is not attractive. Broad straight streets have been cut through the old bazaars, and take away its character. A Persian-speaking infant adorned with eyelashes as long as ospreys conducted us to the necessary officials, and these in their turn showed us a fine polygonal grave-tower of the XIIth century, which is known as the grave of the Mother of Hulagu and is built of plum-red brick arranged in patterns and inscriptions. The effect of this cosy old material, transferred as it were from an English kitchen-garden to the

service of Koranic texts, and inlaid with glistening blue, is surprisingly beautiful. There is a Kufic frieze inside, below which the walls have been lined with nesting-holes for pigeons.

We have conceived the idea of riding from here direct to Miana, thus cutting off two sides of a triangle with Tabriz at its apex. This should take us through unknown country, unknown at least architecturally; it is empty enough on the map. Horses are the difficulty. We agreed to one owner's price; at which he was much taken aback, having lately lost his wife, and having no one to care for his children during the journey. An hour's argument overcame this objection. But then, having seen the horses, we revived it on our own account, to escape from the bargain. The innkeeper is looking for others. We hope to start tomorrow evening. It is the custom in this country to start in the evening.

Tasr Kand

(c. 5000

ft

.),

October 17th

.âI have done my best with the orthography of this place, though it is not important, consisting of one house, and that only a farsakh from Maragha. The farsakh (Xenophon's para-sang) will be of interest to us now. It has been “stabilised” at four miles, but in common parlance varies from three to seven.

Our sheepskin coats and sleeping-bags are spread in an upper room. Through the unglazed window peer the tops of poplars and the last gleam of a sky that threatens winter.⦠A match flickers, a lantern lights up the asperities of the mud wall; the window goes black. Abbas the policeman crouches over a brazier, heating a cube of opium in a pair of tongs. He has just given me a puff, which tasted of potato. The muleteer in the corner is named Haji Baba. Christopher is still reading

Gibbon. Chicken and onions are simmering in a pot. And I reflect that had we foreseen this journey we might have brought some food, and also insecticide.

The officials in Maragha had heard of the Rasatkhana, which means “star-house” or observatory; but none had ever seen it. It was built by Hulagu in the XIIIth century, and its observations were Islam's last contribution to astronomy till Ulugh Beg revised the calendar at the beginning of the XVth. We set out early, breasted a mountain at full gallop, and found ourselves on a level table, where various mounds were approached from four points of the compass by straight cobbled paths intersecting at right angles. These paths, we supposed, were constructed to assist astronomical calculations; the mounds were the remains of buildings. But if here was our objective, where was the rest of the party, the Mayor, Chief of Police, and Military Commandant, who had preceded us? As our escort galloped hither and thither in search of them, we stood on the edge of the table, overlooking a great stretch of country with Lake Urmiya in the distance, and half expecting hounds to go away from a covert of poplars at the foot of the mountain. Suddenly the missing functionaries were discovered half way down the precipice at our feet, and literally underneath us; for as we slithered down to them, leading the horses, we saw that the rock had been hollowed away in a semicircle, and that in the middle of this was the entrance to a cave. The latter may originally have been natural, but had certainly been artificially enlarged.

Inside the cave we found two altars, one facing the entrance, southward, and the other on the right, or east. Each was hewn from the living rock, and situated in a kind of raised chancel with a pointed vault. A rough mihrab was carved in the wall behind the altar on the right, pointing away from Mecca. On either side of the

back altar were entrances to two tunnels. These gave on to small chambers, whose walls had scoops in them for lamps, and then went on, but were too clogged with earth for us to follow them. We wondered if they had ever communicated with the observatory above, and if so, whether observations were taken by daylight. They say it is possible to see stars from the bottom of a well when the sun is shining.

While I was photographing the interior of the cave, and thinking how uninteresting the results would seem to others, Christopher overheard the Chief of Police whisper to the Military Commandant: “I wonder why the British Government wants photographs of this cave”. Well he might.

Sitting on their haunches, the horses had been dragged down the cliff to the village at the bottom. We slid after them, to find fruit, tea, and arak awaiting us in the chief house.

As we left the town this evening, I espied another XIIth-century tower just outside the gate, again of old strawberry brick, but square, and mounted on a foundation of cut stone. Three of the sides were divided each into two arched panels, in which the bricks were arranged in tweed patterns. The corners were turned with semicircular columns. On the fourth side, one big panel, framed in a curving inset, surrounded a doorway adorned with Kufic lettering and blue inlay. The interior disclosed a shallow dome upheld by four deep, but very low, squinches. There was no ornament here, and none was needed; the proportions were enough. Such classic, cubic perfection, so lyrical and yet so strong, reveals a new architectural world to the European. This quality, he imagines, is his own particular invention, whatever may be the other beauties of Asiatic building. It is astonishing to find it, not only in Asia,

but speaking in an altogether different architectural language.