The Road to Oxiana (6 page)

Read The Road to Oxiana Online

Authors: Robert Byron

At the turnstile, that final outrage, a palsied dotard took ten minutes to write out each ticket. After which we escaped from these trivialities into the glory of Antiquity.

Baalbek is the triumph of stone; of lapidary magnificence on a scale whose language, being still the language of the eye, dwarfs New York into a home of ants. The stone is peach-coloured, and is marked in ruddy gold as the columns of St. Martin-in-the-Fields are marked in soot. It has a marmoreal texture, not transparent, but faintly powdered, like bloom on a plum. Dawn is the time to see it, to look up at the Six Columns, when peach-gold and blue air shine with equal radiance, and even the empty bases that uphold no columns have a living, sun-blest identity against the violet deeps of the firmament. Look up, look up; up this quarried flesh, these thrice-enormous shafts, to the broken capitals and the cornice as big as a house, all floating in the blue. Look over the walls, to the green groves of white-stemmed poplars; and over them to the distant Lebanon, a shimmer of mauve and blue and gold and rose. Look along the mountains to the void: the desert, that stony, empty sea. Drink the high air. Stroke the stone with your own soft hands. Say goodbye to the West if you own it. And then turn,

tourist

, to the East.

We did, when the ruins closed. It was dusk. Ladies and gentlemen in separate parties were picnicking on a grass meadow, beside a stream. Some sat on chairs by marble fountains, drawing at their hubble-bubbles; others on the grass beneath occasional trees, eating by their own lanterns. The stars came out and the mountain slopes grew black. I felt the peace of Islam. And if I mention this commonplace experience, it is because in Egypt and Turkey that peace is now denied; while in India Islam appears, like everything else, uniquely and exclusively Indian. In a sense it is so; for neither man nor institution can meet that overpowering environment without a change of identity. But I will say this for my own sense: that when travelling in Mohammadan India without previous knowledge of Persia, I compared myself to an Indian observing European classicism, who had started on the shores of the Baltic instead of the Mediterranean.

Yesterday afternoon at Baalbek, Christopher complained of lassitude and lay on his bed, which deferred our going till it was dark and bitterly cold on top of the Lebanon. On reaching Damascus, he went to bed with two quinine tablets, developed such a headache that he dreamt he was a rhinoceros with a horn, and woke up this morning with a temperature of 102, though the crisis is past. We have cancelled our seats in the Nairn bus for tomorrow, and booked them for Friday instead.

Damascus

,

September 21st

.âA young Jew has attached himself to us. This happened because there is a waiter in the hotel who is the spit of Hitler, and when I remarked on the fact the Jew, the manager, and the waiter himself broke into such paroxysms of laughter that they could hardly stand.

As Rutter and I were crossing a bit of dusty ground left waste by the French bombardment, we saw a fortune-teller making marks on a tray of sand, while a poor woman and her emaciated child awaited news of the child's fate. Near by was a similar fortune-teller, unpatronised. I squatted down. He put a little sand in my palm and told me to sprinkle it on the tray. Then he dabbed three lines of hieroglyphics in the sand, went over them once or twice as though dealing out patience cards, paused in thought before making a sudden deep diagonal, and spoke these words, which Rutter, who once spent nine months in Mecca disguised as an Arab, may be supposed to have translated with sufficient accuracy:

“You have a friend of whom you are fond and who is fond of you. In a few days he will send you some money for the expenses of your journey. He will join you later. You will have a successful journey.”

My blackmailing powers, it seems, are working of their own accord.

The hotel is owned by M. Alouf, whose children inhabit the top floor. One evening he led us into an airless cellar lined with glass cases and a safe. From these he took the following objects:

A pair of big silver bowls, stamped with Christian symbols and a picture of the Annunciation.

A document written on mud-coloured cloth, between three and four feet long and eighteen inches broad, purporting to be the will of Abu Bakr, the first Caliph, and said to have been brought from Medina by the family of King Hussein in 1925.

A Byzantine bottle, of dark-blue glass as thin as an egg-shell, unbroken, and about ten inches high.

A gold Hellenistic head, with parted lips, glass eyes, and bright blue eyebrows.

A gold mummy in a trunk.

And a silver statuette nine and a half inches high, which, for lack of anything to compare it with, M. Alouf called Hittite. This object, if genuine, must be one of the most remarkable discoveries of recent years in the Near East. The figure is that of a man, with broad shoulders and narrow hips. On his head he wears a pointed cap as tall as his own body. His left arm is broken; his right carries a horned bull in its crook and holds a sceptre. Round the waist are bands of wire. This wire, the sceptre, the tail and horns of the bull, and the cap are all of gold. And the gold is so pliable that M. Alouf gaily bent the sceptre at a right-angle and put it straight again. No persuasions could induce him to let me photograph the object. One wonders when and how it will be rescued from that cellar.

Christopher got up on Wednesday, and Rutter took us to tea with El Haj Mohammad ibn el Bassam, an old man of seventy or more, dressed in Bedouin clothes. His family befriended Doughty and he is a famous figure to Arabophils. Having made a fortune out of camels in the War, he lost £40,000 after it by speculating in German marks. We had tea at a marble table, which the height of the chairs just enabled us to touch with our chins. The noise of the Arabic conversation, punctuated by gurks and gulps, reminded me of Winston Churchill making a speech.

The Arabs hate the French more than they hate us. Having more reason to do so, they are more polite; in other words, they have learnt not to try it on, when they meet a European. This makes Damascus a pleasant city from the visitor's point of view.

IRAK

:

Baghdad

(115

ft

.),

September 27th

.âIf anything on earth could have made this place attractive by

contrast, it was the journey that brought us here. We travelled in a banana-shaped tender on two wheels, which was attached to the dickey of a two-seater Buick and euphemistically known as the aero-bus. A larger bus, the father of all motor-coaches, followed behind. Hermetically sealed, owing to the dust, yet swamped in water from a leaky drinking-tank, we jolted across the pathless desert at forty miles an hour, beaten upon by the sun, deafened by the battery of stones against the thin floor, and stifled by the odour of five sweating companions. At noon we stopped for lunch, which was provided by the company in a cardboard box labelled “Service with a Smile”. It will be Service with a Frown if we ever run transport in these parts. Butter-paper and egg-shells floated away to ruin the Arabian countryside. At sunset we came to Rutbah, which had been surrounded, since I lunched there on my way to India in 1929, by coolie lines and an encampment: the result of the Mosul pipe-line. Here we dined; whiskies and sodas cost six shillings each. At night our spirits lifted; the moon shone in at the window; the five Irakis, led by Mrs. Mullah, sang. We passed a convoy of armoured cars, which were escorting Feisal's brothers, ex-King Ali and the Emir Abdullah, back from Feisal's funeral. Dawn discovered, not the golden desert, but mud, unending mud. As we neared Baghdad, the desolation increased. Mrs. Mullah, till now so coy, hid her charms in a thick black veil. The men brought out black foragecaps. And by nine o'clock we could have imagined ourselves at the lost end of the Edgware Road, as the city of the Arabian Nights unfolded its solitary thoroughfare.

It is little solace to recall that Mesopotamia was

once

so rich, so fertile of art and invention, so hospitable to the Sumerians, the Seleucids, and the Sasanids. The prime fact of Mesopotamian history is that in the XIIIth

century Hulagu destroyed the irrigation system; and that from that day to this Mesopotamia has remained a land of mud deprived of mud's only possible advantage, vegetable fertility. It is a mud plain, so flat that a single heron, reposing on one leg beside some rare trickle of water in a ditch, looks as tall as a wireless aerial. From this plain rise villages of mud and cities of mud. The rivers flow with liquid mud. The air is composed of mud refined into a gas. The people are mud-coloured; they wear mud-coloured clothes, and their national hat is nothing more than a formalised mud-pie. Baghdad is the capital one would expect of this divinely favoured land. It lurks in a mud fog; when the temperature drops below 110, the residents complain of the chill and get out their furs. For only one thing is it now justly famous: a kind of boil which takes nine months to heal, and leaves a scar.

Christopher, who dislikes the place more than I do, calls it a paradise compared with Teheran. Indeed, if I believed all he told me about Persia, I should view our departure tomorrow as a sentence of transportation. I don't. For Christopher is in love with Persia. He talks like this as a well-bred Chinaman, if you ask after his wife, will reply that the scarecrow of a bitch is not actually deadâmeaning that his respected and beautiful consort is in the pink.

The hotel is run by Assyrians, pathetic, pugnacious little people with affectionate ways, who are still half in terror of their lives. There is only one I would consign to the Baghdadis, a snappy youth called Daood (David), who has put up the prices of all cars to Teheran and referred to the arch of Ctesiphon as “Fine show, sir, high show”.

This arch rises 121½ feet from the ground and has a

span of 82. It also is of mud; but has nevertheless lasted fourteen centuries. Photographs exist which show two sides instead of one, and the front of the arch as well. In mass, the ill-fired bricks are a beautiful colour, whitish buff against a sky which is blue again, now that we are out of Baghdad. The base has lately been repaired; probably for the first time since it was built.

The museum here is guarded, not so that the treasures of Ur may be safe, but lest visitors should defile the brass of the show-cases by leaning on them. Since none of the exhibits is bigger than a thimble, it was thus impossible to see the treasures of Ur. On the wall outside, King Feisal has erected a memorial tablet to Gertrude Bell. Presuming the inscription was meant by King Feisal to be read, I stepped up to read it. At which four policemen set up a shout and dragged me away. I asked the director of the museum why this was. “If you have short sight, you can get special leave”, he snapped. So much, again, for Arab charm.

We dined with Peter Scarlett, whose friend, Ward, told a story of Feisal's funeral. It was a broiling day and a large negro had made his way into the enclosure reserved for the dignitaries. After a little time he was removed. “God damn,” yelled the Commander of the English troops, “they've taken away my shade.”

Money was waiting for me here, as the fortune-teller promised.

PART II

PERSIA

:

Kirmanshah

(4900

ft

.),

September 29th

.âWe travelled for twenty hours yesterday. The effort was more in argument than locomotion.

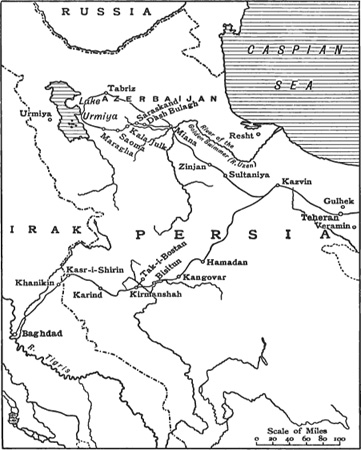

A burning dust-storm wafted us along the road to Khanikin. Through the murk loomed a line of hills. Christopher grasped my arm. “The ramparts of Iran!” he announced solemnly. A minute later we breasted a small incline and were on the flat again. This happened every five miles, till an oasis of sour green proclaimed the town and frontier.

Here we changed cars, since Persia and Irak refuse admission to one another's chauffeurs. Otherwise our reception was hospitable: the Persian officials offered us their sympathy in this disgusting business of customs, and kept us three hours. When I paid duty on some films and medicines, they took the money with eyes averted, as a duchess collects for charity.

I remarked to Christopher on the indignity of the people's clothes: “Why does the Shah make them wear those hats?”

“Sh. You mustn't mention the Shah out loud. Call him Mr. Smith.”

“I always call Mussolini Mr. Smith in Italy.”

“Well, Mr. Brown.”

“No, that's Stalin's name in Russia.”

“Mr. Jones then.”

“Jones is no good either. Hitler has to have it now that Primo de Rivera is dead. And anyhow I get confused with these ordinary names. We had better call him Marjoribanks, if we want to remember whom we mean.”

“All right. And you had better write it too, in case they confiscate your diary.”

I shall in future.

At Kasr-i-Shirin we stopped another hour, while the police gave us a permit for Teheran. Then indeed the grandeur of Iran unfolded. Lit from behind by the fallen sun, and from in front by the rising moon, a vast panorama of rounded foothills rolled away from the Sasanian ruins, twinkling here and there with the amber lights of villages; till out of the far distance rose a mighty range of peaks, the real ramparts at last. Up and down we sped through the fresh tonic air, to the foot of the mountains; then up and up, to a pass between jagged pine-tufted pinnacles that mixed with the pattern of the stars. On the other side was Karind, where we dined to the music of streams and crickets, looking out on a garden of moon-washed poplars and munching baskets of sweet grapes. The room was hung with printed stuffs depicting a female Persia reposing in the arms of Marjoribanks, on whom Jamshyd, Artaxerxes, and Darius looked down approvingly from the top of the arch at Ctesiphon.