The Road to Ubar (19 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clapp

"But enough, woman, enough!" interjected one of the men, his eyes smarting from the smoke.

"Too bad for you," she said, laughing, and led the way outside. The men downed handfuls of pine nuts, the last of their breakfast, and followed.

With clouds of incense billowing skyward, the little group circled the compound's corral. And in the light of day we saw that the men were wearing elegant purple robes looped over their right shoulders, a rarely seen traditional dress. They paused to offer prayers and incense at the entrances to the three domed huts in which their cattle had spent the night. The incense wasn't to offset the smell of the cattle (though it helped); rather, it was offered to protect the animalsâfrom djinns.

The mountains of Dhofar, the Shahra believed, were rife with djinns, invisible spirits born of smokeless fire. By day they dwelt at waterholes and in dark gullies. Though some djinns were friendly, most were not. Given to inflicting misery and misfortune, they could take the form of whirlwinds and raging sandstorms. Or they could shape-change into reptiles, various beasts, or even humans. Their true identity was discernible only by their feet, which were like the hoofs of asses. In great numbers, djinns were abroad at night, especially on Wednesdays and Fridays. Flying out across the land, they uttered screams so loud and penetrating that anyone unwisely out and about would lose his wits. It was a time to bar doors and windows and leave the darkness to its owners.

Now, in the early morning, frankincense dispelled any lingering djinns, and the cattle could be led off to pasture with a reasonable assurance of safety. The herdsmen would nevertheless be wary of strangers going their way. In broad daylight, djinns could manifest themselves as fellow travelers, leading men and animals astray, often to their deaths.

The cattle disappeared over a hill, their passage marked by a lingering cloud of dust that hung motionless. "A good sign," Ali Achmed noted, looking off across the land. "No djinns."

The Shahra remaining at the settlement turned to their daily tasks. The dwellings of men and beasts were swept out. A little girl worked at a loom; her mother churned milk in a leather bag. A dog lazed in the sun, one eye open, lest it be kicked by a nearby goat.

Despite everyone's diligence, it appeared the djinns had worked some mischief. A little boy hadn't been able to shake off a bad cold, and something needed to be done. The settlement's matriarch added fresh frankincense to a burner and led the child to the center of the corral. Round and round she circled him, enveloping him in incense. She chanted, "Look at this your sacrifice: frankincense and fire. From the eye of the evil spirit; of mankind, from afar; of kindred, nearby, and from afar. Be redeemed from the evil spirit. Look at this your sacrifice: frankincense and fire."

7

She passed the burner to an older man, who continued the ritual, circling and chanting. Frankincense and fire were a potent combination. The incense brought the blessing of Allah, and fireâeven a small sparkâwas believed even more effective than the name of Allah in curing possession. Fire dispelled djinns, creatures born of fire.

As the day wore on, tribespeople came and went. A woman came by in search of a lost chicken. Assault rifles jauntily cradled in the crooks of their arms, three young men stopped by for coffee; they had been down to the coast and shared news of the outside world.

With Ali Achmed translating, we asked about the People of 'Ad. Yes, they all agreed, the 'Ad were their long-ago ancestors. The Shahra knew about Ubar and referred to the city's inhabitants as "Irema." We were startled by this, for Irem (or Iram), we believed, was the Koran's name for Ubar. Here was a living link between the two principal names for our city!

8

The Irema, the Shahra told us, were a rich if wicked people who ate off golden plates. That is, until "their city turned over."

A young man with the mustache of a brigand chuckled and told us that to the Shahra the phrase "Take him to the Irema" means "Get rid of him."

The oldest of the group regaled us with the tale of how the golden treasure of Ubar, spirited away from the doomed city, was to be found in a desert cave, guarded by a snake.

"Was the snake a djinn?" I asked.

"How could that be?" he shot back. "Do snakes have feet?"

I realized my mistake. To be a djinn you have to have hoofs, so a snake can't be a djinn. We agreed that snakes can still be pretty nasty.

The storyteller continued, "One way to keep the snake away [from the treasure] was to have a holy man read to it." This, he said, led two thieves to find themselves a holy man and have him read to the snake while they helped themselves to Ubar's riches.

The old man's voice fell to a whisper: "You see, they were going to cut the holy man out. But he, being both holy and wise, suspected this. He stopped reading. The snake ate one thief; the other ran away. Nobody's gone there since."

The thought crossed my mind: if we couldn't find Ubar, maybe we could find the cave. Read to the snake.

Late in the afternoon, the family's cattle reappeared, and with whistles and trilling shouts, were herded back into their huts. In the clan's living quarters, incense was again burned, and a

majlis,

a communal gathering, began. In their ancient language, the Shahra sang a rousing song of revenge, then shifted to a melancholy melodic recital of lost love and found wisdom. They sang a capella and antiphonally, with evenly divided groups of men answering each other. They drew their voices across the words like bows across strings, as if to echo a psaltery of the past. In this isolated settlement, speech and songâand a way of lifeâhad been preserved since the ancient days of the incense trade.

At the end of a long and rewarding day, we took leave of the Shahra and headed back to Salalah. We kept an eye out for djinn, but, it being Thursday, we were unmolested. (It's Wednesdays and Fridays that you must beware.) As we bumped along the dirt track, we passed other Shahra settlements, illuminated by kitchen fires, occasional gas lanterns, and the passing glare of our headlights. If the Shahra live now as the People of 'Ad once lived, it was understandable why tangible remains of the 'Ad had proved so elusive. Their culture may have been complex and literate, but their surviving artifacts would have been few. The impressively domed dwellings and most of their contents were perishable. About all that would survive for even a century would be fragments of fired pottery, foundation stones, and the stones marking their departure from their life and land.

Their graves.

T

HE VERY NEXT DAY

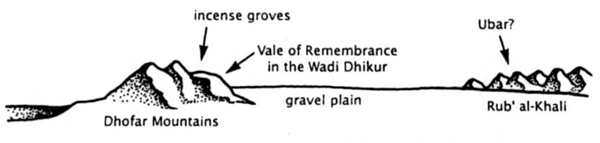

, Ali Achmed took us beyond the settlements of the Shahra to a long, meandering valleyâthe course of the Wadi Dhikurâthat dropped from the tableland of the Dhofar Mountains to the desert beyond.

The Shahra knew the valley of the Wadi Dhikur as the Vale of Remembrance, for this was where they had laid their dead to rest for hundreds, even thousands, of years. An eerie mist shrouded the valley's upper reaches, draining the color from its rock walls. The air was clammy, and not a breath of wind stirred. The place was oppressive. The first graves we encountered were Islamic, oriented to Mecca. Two stone slabs marked a man's burial, and three marked a woman's. Ali motioned to where, higher on the valley's wall, stone blocks sealed a series of caves. We scrambled up and peered into a breach in the stonework. From the darkness within, a congregation of skulls returned our gaze. Patches of their head cloths were still intact. Other bones were scattered about the cave. Since it was not oriented to Mecca, this tomb appeared to be pre-Islamic, earlier than the 600s. We could have reached in and collected sample textiles for carbon dating, but we didn't, for we felt ourselves outsiders to this majlis of the dead. They, not we, belonged in the valley.

Returning to the valley floor, we shared, rather quietly, the lunch Kay had laid out on the tailgate of a Discovery. Ali Achmed ate only half of his turkey sandwich; the rest he scattered in the air.

"Ali? Looking after the birds?"

Cross-section of the Dhofar region of Oman

"Feeding the djinns," he replied with a laugh that wasn't really a laugh. Even to the enlightened, djinns are not to be dismissed. They stalk the pages of the Koran, where they are considered, after man and animal, a third creation of Allah. 'Afrits, a particularly troublesome brand of djinn, dwell in graveyards. They are the spirits of wicked men turned away from Paradise, doomed to haunt their place of burial.

"And who was wickeder than the People of 'Ad?" asked Ali Achmed, paraphrasing a verse from the Koran.

We drove on down the Vale of Remembrance. Shading his eyes from the afternoon sun, Ali scanned the widening valley.

"The stones," he said, "you must see the stones. They're part of this."

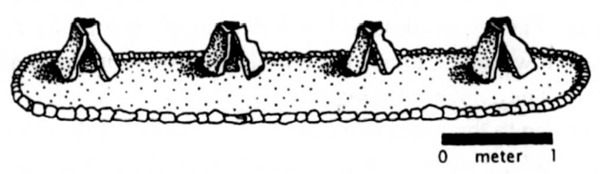

He directed us to a row of stone monuments, each consisting of three unfinished slabs of stone tilted together to form a crude two- to three-foot-high pyramid, known as a trilith ("three-rocks").

Dhofar triliths

Line of triliths viewed from above

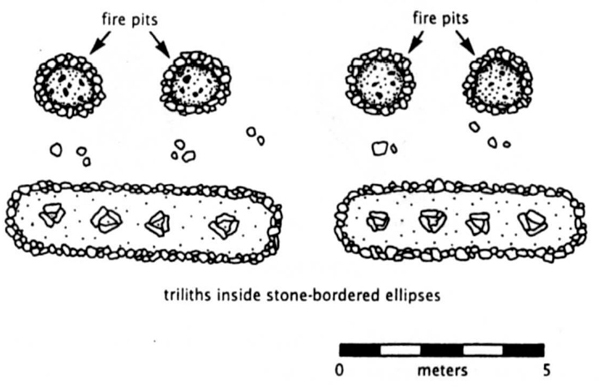

Rows of triliths have been reported throughout southeastern Arabia. This site had eight pyramids in a line and, parallel to them, four fire circles. Elsewhere we found rows of as few as three and as many as twenty-five triliths.

The triliths of the Vale of Remembrance were as old as the People of 'Ad. Ali Achmed showed us where, the year before, he had dug beneath two of them and discovered ash, andâvia an English friendâsent it off for carbon dating. His ash samples dated to 60 and 110

B.C.

(plus or minus approximately one hundred years).

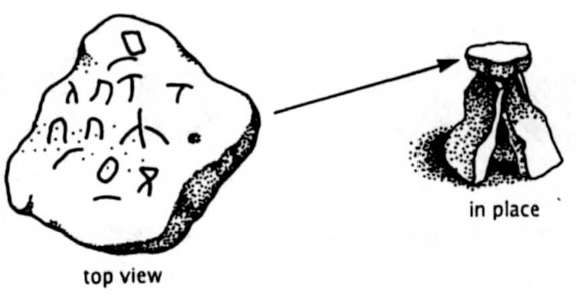

Ali was convinced that the triliths had once been "quadriliths," that each set of three stones once supported a capstone, which over the years could have easily tumbled off. Spotting a rock that to us looked like any other, he crouched down, dug around it, and turned it over. It was inscribed with well-preserved letters from the same alphabet used in the rock art of the mountain caves.

His fellow Shahra, Ali Achmed told us, held that triliths were memorials to the ancient dead, a reasonable idea considering the funerary nature of this valley.

1

It has also been suggested that triliths were route markers for passing caravans or sites for the ritual crucifixion of ibexes, desert animals whose crescent horns symbolized the crescent moon, the principal deity of pre-Islamic Arabia.