The Road to Ubar (22 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clapp

Long ago, before the road had been claimed by the sands, a great cloud of dust would have risen from the far horizon, sent skyward by hundreds upon hundreds of camels moving at once. Wary of marauders, outriders with long lances would have kept the animals in close ranks as they indignantly bleated and gurgled. They would have slowly approached where we stood and passed on by, bearing frankincense north to the great markets of the ancient world.

We camped by the Ubar road at the north end of the valley, at the edge of the L-shaped formation we had checked out on our reconnaissance, which had proved to be an ancient lakebed. Ron walked out across it and, with a hand auger, took a coring of sediments that could later be used to date when the lake had formed and flourished. His educated guess was that it had dried up sometime between 7000 and 8000

B.C.

Juri scanned the shores of the lakebed and wondered aloud, "If I came here to hunt and maybe fish, where would I camp?" "Higher ground," he answered himself, "where I could spot game and enemies." With that, he was off.

An hour later Juri was back, his every pocket clinking and bulging with rocks. No more than two hundred feet away, just out of our sight, he had found a large Neolithic (from 5000

B.C.

on) campsite. He couldn't be sure, but it appeared to be divided by walkways. Scattered everywhere, broken and intact, were the utensils of Stone Age life, as many as ten thousand of them. Axe blades, animal skin scrapers, mauls, and arrowheads.

"But Stone Age," I wondered, "wouldn't that be..."

"Yes," he completed the sentence, "too early for what we're looking for."

As the moon rose and Mr. Gomez served us "Apricots, dried" and "Cookies, 2 choc, chip," we discussed the finds of the day and listened as archaeologist Juri and geologist Ron pieced together a rough chronology for the valley...

Perhaps seven thousand years ago, Neolithic hunter-gatherers had camped on a rise overlooking what was then a small lake. Considering the abundance of artifacts Juri had found, it had been a favored stopping place for hundreds, even thousands, of years. But when seasonal rains no longer reached this far inland, the lake dried up, and early man moved on, possibly to the south. The land, once savanna, became desert. The windblown sands of dry lakes and rivers formed dunesâsmall at first, then larger, ultimately enormous.

Sometime before 1500

B.C.

(the approximate date of Juris orange potsherd), a more technologically advanced peopleâalmost certainly the People of 'Adâpassed this way but didn't linger, other than to build simple shelters and corrals. The valley was a rest stop on the Incense Road.

"What about Ubar?" Kay asked.

There was a considerable pause, then Ron broke the silence. "To me, it comes down to water. No water, no city. There's certainly no water out here now, and frankly, I doubt that there was three or four thousand years ago. Considerably before that, yes. But when lakes like this dried up, that was it." Juri nodded in agreement and pointed out that if the region's lakes had been spring-fed rather than dependent on rainfall, early man would have followed the springs down, digging them out as the water table dropped. That is how springs become wells. One or two almost certainly would still be in use.

We discussed the practicality of a city out here. Uncertain, shifting sands and violent sandstorms would have been a problem. Beyond that, what would have been a city's imperative? If Ubar was a staging point for caravans and a trading cityâan "Omanum Emporium"âwhat was it doing sixteen days by camel from the incense groves? Out here, Ubar's control of the incense trade would have been shaky at best. Judging from our space images, there already would have been at least two opportunities to bypass such a settlement and avoid the tolls and tribute that the ancient Arabians were fond of extracting.

Simply put, a city out here would have been an economic disaster.

For the last few days, our conversation had been determinedly on the light side. We now knew why. Humor had kept us from facing the fact that we might well be chasing, as the bedouin doggerel described it, "a ghostly city of the mind."

Though we were all tired, nobody turned in for a while. The valley had spoken to us and told us what we didn't want to hear. But it nevertheless had affirmedâwith a bit of orange pottery and an impressive roadâthat the people we sought had passed through. How and where had they begun their journey? Answer that, and we might answer the mystery of Ubar.

The valley also showed us that the Rub' al-Khali was not, as it has often been called,

nature maligna.

The Arabs once believed that the stars were the lamps of thousands of angels. They shone brightly now, as did the crescent moon. Every curve of every dune was thrown into relief, cool blue upon dark blue. In its stillness, the valley inspired not fear, or even uneasiness, but serenity.

There is a little-known alternative translation for the phrase "Rub' al-Khali." Though it has been taken to mean the Empty Quarter since at least the 1400s, it may once, far longer ago, have meant Moon Quarter. The ancient Arabians associated different territories with different gods. The Arabian sands, then, would have been the realm of the moon god, ascendant and paramount among the gods. Rising to the sigh of cool breezes, the moon spelled relief from the heat of the day and was a lamp for caravans moving by night. The moon presided over the stars, which in turn foretold the destiny of men and nations.

By the moon's waxing and waning, all time was measured. All birth, life, and death. Long ago, an invocation cited the moon as...

...a creature of night to signify the days.

May the dead rise and smell the incense.

5

Monday, December 16. Day 4: the road toâor from?âUbar.

We followed the Ubar road beyond our valley and deeper into the dunes. Our Landsat 5 / SPOT composite image was very helpful; we could cruise across the sands directly to a "blowout," a place where the road lay exposed for no more than a few hundred feet. Juri suspected that if we looked long and hard enough, we would find more evidence of incense caravans and their campsites. And, judging from the lakebeds dotting our space imagery, we would find an abundance of even earlier Neolithic sites. The idea of Neolithic sites led Juri to speculate on why the bedouin believed Ubar lay hidden out here in the dunes.

"Say you're a bedouin of the last century or so, and you find a Neolithic artifact, like a big grinding stone, which can be pretty impressive. Aha, you think, you're on the outskirts of Ubar! And your imagination gets all fired up thinking of the treasure that must be hidden under the next dune, or the next one after that. And so not only the bedouin but explorers like Bertram Thomas and Wendell Phillips get to thinking this is where to find Ubar."

Late in the morning of that fourth day in the dunes, we reached a point of no return. Getting lost two days ago had cost us considerable fuel, and now we had just enough to make it back to the beginning of the Rub' al-Khali, where we had dropped off a reserve 55-gallon drum of gas.

Reluctantly, we turned back on our tracks and, without incident, crossed the dunes that guarded our lost valley. We were then able to find a more direct route back to the Wadi Mitan. As we drove, we talked back and forth by radio. What next? Our best (and about only) hope was that we had found the Ubar road, but that it was not the road

to

the city, but

from

it. Ubar might lie in the direction we were now heading, in open desert closer to the incense groves. This was logical, but it was also unlikely, for there was hardly an inch of the open desert that hadn't been crisscrossed by sharp-eyed bedouin who, we had found, were perfectly willing to share the secrets of their land.

After the Wadi Mitan we knew we were more or less following the Ubar road, but our earlier reconnaissance had told us that we would have a hard time making it out. According to our space images, sometimes we were right on it, sometimes a few kilometers to the north or south. We considered how and where we might look for Ubar. A good start would be to explore where the road crossed wadis that once might have provided a water supply. We could also, centimeter by centimeter, again go over our space images. Had we overlooked any promising anomalies? At this point we doubted it.

It was after dark when we made it back to our first Rub' al-Khali campsite. Our fuel drum was exactly where we had left it, but emptyâa blessing, we guessed, upon a passing bedouin's pickup. No matter, we had enough gas to make it on to the little oasis at Shisur, and maybe even back to the airbase at Thumrait.

Tuesday, December 17. Day 5: to Shisur.

Desert winds can drive you to distraction. Or you may pray for them. The next day was hot and deathly still. The Discoverys kicked up huge clouds of sand that just hung there. Only the first vehicle had a view of where we were going; the others followed blindly. An hour or so out, we stopped to regroup. The cloud that had enveloped us cleared. Across the sandy plain, not all that far away, shining white buildings and towers floated in a mirage.

"Must be Ubar," Kay remarked, not very seriously. "How could we have missed it?"

Ran steadied his binoculars. "It's a housing development, would you believe," he said. "Tsk, tsk." Actually, it was the settlement of Shisur, site of the ruined fort we had seen on our reconnaissance and a dozen brand-new houses and a mosque that the government had recently completed for the principal sheiks and families of the local Rashidi. As we drove on, the mirage melted, and we could make out little kids darting between houses and alerting everyone to our arrival.

Through the desert telegraph, Shisur had heard we might be coming, and its thirty-six souls, from wide-eyed infants to white-bearded elders, all dressed in traditional Omani robes, turned out to greet us. They offered warm

salaam aliechems

; for whatever peculiar reason the strangers had come here, peace be upon them. Baheet ("Luck") ibn Abdullah ibn Salim was the imam, the religious leader of Shisur. He and his friend Mabrook ("Congratulations") proudly toured us through the newly built settlement and accompanied us as we took another look at the site's ruined fort. They confirmed that it had been built in the early 1500s by one Badr ibn Tuwariq.

The dominating feature of the ruined fort was a tower, and with more time to examine it, Juri was struck by a curious feature. Near its top, the quality of the masonry became slapdash. And the shape of the tower changed from square to round.

"You know, it could just be that this Sheik Tuwariq didn't build the fort, but

rebuilt

it," Juri remarked. "The original structure could be medieval, even earlier."

The fort was perched on the edge of the distinctive steep-walled sinkhole that gave Shisur its name. In Arabic, we were told,

shisur

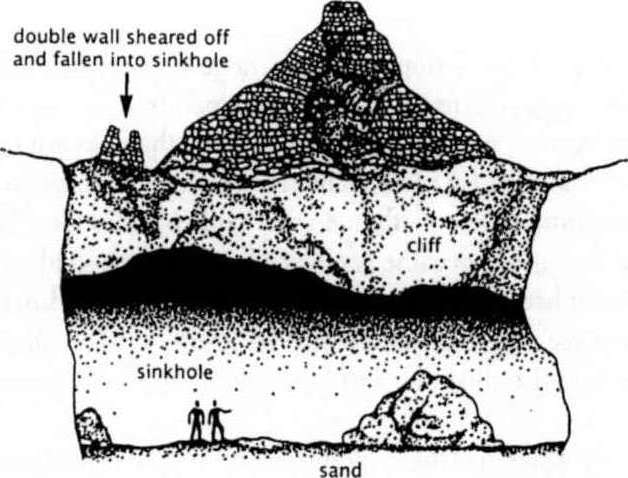

meant "the cleft." Geologist Ron and archaeologist Juri led the way as we walked down a sloping rubble ridge to the sinkhole's sandy floor. After some discussion, they determined that we were in what had once been an underground cavern. More than likely it had been filled with water. But at some point in the past, either through natural causes or human use or both, the water table had dropped. Emptied of water, the cavern became geologically unstableâand collapsed. Moreover, it had collapsed

after

the fort had been built. Looking up, you could see where a wall connected to the fort had sheared off, tumbled into the sinkhole, and lay buried in the sand beneath our feet.

The ruin at Shisur

In myth, Ubar had been destroyed in a great cataclysm whose exact nature was unclear. Different tales had spoken of a great wind, a "divine shout," or the city sinking into the sands. The Shahra tribesmen back in the mountains had told us that Ubar came to an end when "the city turned over." Could what happened at Shisur also have happened at Ubar? Might Shisur be Ubar? For that to be possible, the ruins here would have to be more than five hundred years old. Our hopes rose when Baheet and Mabrook led us to petroglyphs etched on the far wall of the sinkhole. They appeared old, but as Juri pointed out, they might date back only a hundred years or so. Out here, until very recently, time had stood still.