The Road to Ubar (26 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clapp

Sandstone king

The chess set, wonderful though it was, raised a further question. The game is believed to have originated in India in the late 600s, a hundred years or so

after

Ubar's legendary destruction. Did this checkmate our Ubar theories? Juri thought not. The sinkhole, he reasoned, could have collapsed sometime after 150

A.D.

, and the fortress thereupon abandoned. Then, centuries later, ruined Ubar may have been reoccupied.

The Ubarites did not vanish from the face of the earth after fleeing their city; rather, there is evidence that they were absorbed by other tribes (the Shahra of the Dhofar Mountains and the Mahra of the Oman-Yemen borderlands). In time, members of these tribes could have been drawn back to the ruined city and its unique water source. While their animals grazed on what was left of the verdant oasis, they could have whiled away the hours with the newly invented game of chess.

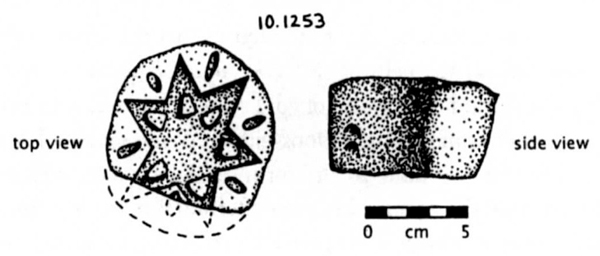

Baheet and Mabrook often dropped by Amy's lab to help out. Particularly when the sky was dark and the wind howled through their village, they would sit for hours, quietly cleaning shards and piecing them together. With the help of a magnifying glass, they translated fragments of Arabic barely visible on Islamic coins. And, forthrightly, they would ask questions that we tended to avoid. Such as: "If this is Ubar, then where's the gold?" Many bedouin assume that no matter what archaeologists say, they are treasure seekers. Why else would they dig in the dirt? Baheet and Mabrook were too sensible for that; nonetheless, they reminded us that the Ubar storied by their grandfathers was a city of ,

,

dhahab ahmar

âred gold.

We hadn't found even a hint of gold. One good reason for this was that we hadn't found any skeletons either. When archaeologists

do

find treasure, it is usually in the form of grave goods, offerings to comfort and aid the deceased in their afterlife. But Juri had found no burials at or near Shisur. One possible explanation was that anyone who died there was taken to the mountains for burial, perhaps in the Vale of Remembrance that we had visited. This would have been likely, we thought, if the fortress of Shisur had been

seasonally occupied.

The People of'Ad might have spent the late spring and summer months in the cooler, monsoon-shrouded Dhofar Mountains, harvesting their precious frankincense. Come fall they could have transported it to Shisur, a staging area for the great caravans striking out across Arabia. When these caravans returned to Shisur in the spring, the People of 'Ad would take their deadâas well as their profits (including any gold)âback to their mountain retreat.

7

So it was that Baheet's blunt "Where's the gold?" led to the working out of a scenario of the annual ebb and flow of life at Shisur. Depending on the time of year when the sinkhole collapsed, there may have been treasure stored in the Citadel. But, Baheet and Mabrook agreed, the 'Ad, when they fled, would not have been so panicked, morose, or witless as to leave any treasure behind.

As the nasty weather allowed, Juris students continued to clear away foundations of towers, walls, and the Citadel. It was hard to tell whether the Citadel was a stronghold, as it first appeared to be, or a temple dedicated to ancient godsâor both. We could only speculate that whoever had raised this fortress had been inspired by more than an elemental need to stave off their enemies.

In terms of productive archaeology, the next weekend was not the time for solving the inner meaning of the Citadel. The weather lapsed back into wretchedness, and only a handful of volunteers showed up. It wasn't the stinging sands, we learned, that kept them away, but the fact that an Omani fighter plane based at Thumrait had plunged into the Arabian Sea. Over the radio we offered our condolences, but were told, oh no, the pilot had ejected and was quite all right.

Our volunteers, a slightly slurred voice informed us, were partying. That was strange, we thought, for weren't our Airwork volunteers responsible for the maintenance of Thumrait's aircraft? Yes, yes, they were, and that was the point. The crash had been due to

pilot error;

a nonstop, sixty-two-hour party was celebrating the fact that

the crash wasn't their fault!

Week five at Shisur

... This was to be the last week for all but Juri and his five students.

For years George Hedges, now back in Los Angeles, had worked tirelessly to organize the expedition and get it financially off the ground. In the field, Ran Fiennes had done a superb job of orchestrating our logistics. We always had what we needed, and Juri never lost a minute as he excavated Shisur. Our original plan had called for the sinking of one or two modest test shafts if we found a site that appeared to be Ubar. As it turned out, with as many as forty people digging at a time, we had brought to light an entire buried fortress and surveyed its surrounding terrain.

Our plan had called for three months in Oman, and now those three months were about up, and our bank account was about done for. There was just enough money left to see Juri and his students through the rest of their work-study semester.

In our last week at Shisur, a radio call alerted us that an Omani Air Force Huey had refueled at Thumrait and was on its way north to Shisur. What good fortune! We could photograph the site from the air. The helicopter and its crew showed up in time for dinner; the English pilot and Omani copilot found it hard to believe that anybody had built

anything

so far out in the desert so long ago.

The next day was clear, with not a breath of wind. We were quickly aloft and circling the site. With the tiny figures of Juris students for scale, it looked bigger than it felt on the ground. We could easily make out the foundations of several towers and see that the site had had not only an outer wall but, most likely, an inner wall to protect the immediate area of the Citadel; it had been all but wiped out in the sinkhole's collapse.

Ubar in ruins

This, we finally believed, was ancient Ubar.

For over a month now, we had worked a puzzle. Its key pieces had to do with pottery types and sequences, architectural plan, and the role of the incense trade. Along the way, some pieces didn't seem to fit. What was a chess set doing here? Where, as Baheet asked, was the gold? In finding what fitted with what, there had been no magic "Eureka!" moment, no time to proclaim "This is Ubar!" and unleash the formidable party potential of our Airwork volunteers. Instead, a picture had slowly formed of a distant time, place, and people, a picture that seen in its entirety was a convincing match for the legendary lost Ubar.

Ubar as it may have been

Key to that match were...

LOCATION

The site was where it was supposed to be. The myth of Ubar had led us to the unremitting desolation of a remote area of Arabiaâand, against all expectation, an impressive fortress.AGE

The site was ancient. In myth, Ubar was founded by Noah's grandson, a first patriarch of the People of'Ad. What we had found dated to 900

B.C.

or earlierâthe very dawn of civilization in this land. Our site was among the oldest, if not

the

oldest, of Arabia's incense-trading caravansaries.CHARACTER

Here was an expression of the Koran's,

dhat al-imad,

city of lofty buildings. And Ubar's eight or more towers guarded a water source that, more than anything else in the surrounding fifty thousand square miles, qualified as "the great well of Wabar" described by the historian Yaqut ibn Abdallah as the city's principal feature. For all its isolation, here was a place where, as in its legend, people prospered and lived well, cooking and dining on the ware of classical civilizations.DESTRUCTION

The legend of Ubar climaxed as the city "sank into the sands." It surely did. Ubar wasn't burned and sacked, decimated by plague, or rocked by a deadly quake. It collapsed into an underground cavern. Of all the sites in all the ancient world,

Ubar came to a unique and peculiar end, an end identical in legend and reality.

As our helicopter, in widening circles, flew out over the desert, Juri pointed out geological traces indicating where springs once broke the surface and supported a substantial oasis. Water, he felt, was the key to our site's identity. Once there had been many springs; finally there was but one, and it still flowed. "In this desert," he later observed, "Ubar could have been hidden anywhere in, say, fifty thousand square miles. But it's here because there's water. Permanent water."

We had just enough fuel to helicopter to the northeast and photograph the nearby low hills where caravans rested before venturing off across the Rub' al-Khali. Returning to earth, we knew that, as almost always in archaeology, we could not identify the site as Ubar without reservation. We could never be 100 percent certain unless we found an inscription that included the word , Ubar. Father Jamme had written this out for us, but doubted that we would ever find it.

, Ubar. Father Jamme had written this out for us, but doubted that we would ever find it.

8

We consoled ourselves with the fact that no telltale inscription has ever been found at what archaeologists have agreed is Homer's Troy. We were fortunate enough to find what we had found.