The Road to Ubar (29 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clapp

Neolithic animal trap at Shisur

When gazelles and oryxes came to drink, beaters would approach from the east and noisily drive them between two rock walls to the west of the spring. The narrowing walls forced the panicked, confused animals into a rock circle. There, waiting hunters would rise up to take their prey with arrows, spears, and nets.

4

At nearby sites, such as Flintknapper's Village, the People of 'Ad would have enjoyed a good life, as good as the late Stone Age allowed. Goats had been domesticated, and their long hair was loomed to create spacious, comfortable tents. Domesticated cattle provided skins, milk, and meat. Though game wasn't as plentiful as it had been when they first settled here, the People of 'Ad sharpened their hunting skills by crafting finer, more effective arrowheads.

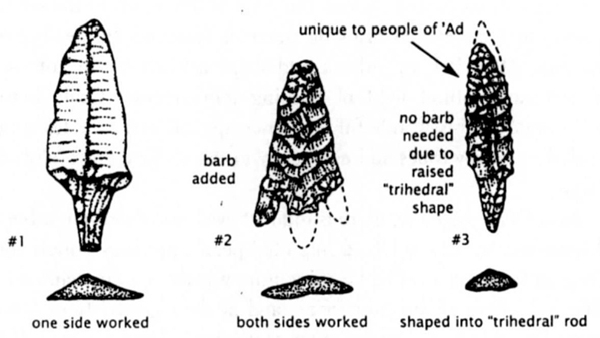

At first the 'Adites worked just one side of their large flint arrowheads, but then, influenced by samples imported from the north, they worked both sides and added a barb. Finally, in an advance that was their own invention, the arrowheads of 'Ad were streamlined and deftly serrated, with a ridge running down the middle. They were contoured "trihedral rods" (as classified by archaeologists).

Evolution of arrowhead technology

This shape could be achieved only with skilled, twisting blows of stone on stone. Found throughout Dhofar, these trihedral rods defined, at an early stage in their existence, the range of the People of 'Ad. Remarkably, it was a territory that would be theirs for the next 5,000 years (circa 4500

B.C.

to 500

A.D.

).

The life of the early 'Adites centered on their campfires. It was there that they crafted their arrowheads and stone tools, and it was there, quite by accident, that they may have discovered the fragrance and uses of frankincense. Imagine an extended family camped at the same place for several months. With the supply of deadfall firewood exhausted, a couple of children might have been given a hand axe and asked to cut an armload of branches from a nearby scraggly tree, no taller than they. As the fire was kindled, an unusually white smoke curled up, and instead of watery eyes and coughs, it prompted appreciative sniffs and sighs. The smoke of the frankincense was sweet and clean. If in their early belief system the People of 'Ad had notions of Paradise, its scent was that of frankincense.

The 'Adites doubtless found many uses for frankincense. What better offering for their animistic and celestial deities? It had practical applications as well. It took the edge off the smell of well-worn garments; it sweetened drinking water; it hastened the healing of wounds. After dark an 'Adite could shape a blade by the intense, almost supernatural light of burning frankincense. Quite naturally, word of this wonderful substance spread, and samples were traded to nearby tribes and eventually to the civilizations of distant lands.

As early as 5000

B.C.,

there is indirect evidence that the northern Mesopotamian city of Ubaid imported pearls, precious stones, and incense from Arabia. The Ubaid culture was in time supplanted by the civilization of the Sumerians, and at their great city of Uruk several bas-reliefs illustrate offerings of incense to the sun god and his consort. Researching Sumerian cuneiform tablets, Juris Zarins found that their deities were in the earliest years purified with the burning of cedar brought from Lebanon. But then, according to a text dated to 2350

B.C.,

these deities were offered incense:

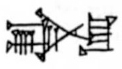

(SHIM = incense)

(SHIM = incense)

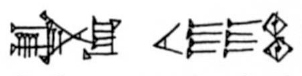

More specifically, the gods were offered what was probably frankincense:

(SHIM.GIG = frankincense)

(SHIM.GIG = frankincense)

The displacement of cedar by frankincense as a temple offering would have been expedited by the domestication of a sure-footed, tough beast of burdenâthe donkey. The first long-range caravans were donkey caravans, and with them a "merchant of aromatics" could have made yearly forays into the heart of Arabia.

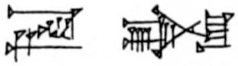

(GARASH.SHIM = merchant of aromatics)

(GARASH.SHIM = merchant of aromatics)

The ritual burning of frankincense became a call to the gods who, as it is recounted in the epic of

Gilgamesh,

"smelled the sweet savor. The gods gathered like flies over the sacrificer." Though the Sumerians didn't have a very high opinion ("like flies") of their gods, smoke curling heavenward conveyed pleas, expressed gratitude, offered atonement. Indeed, the German incense historian Walter Müller believes that throughout the Middle East, frankincense was considered to have unusual expiatory power, much like the power gained by sacrificing an animal, for "its resin was considered to be the blood of a tree, which was taken to be animate and divine."

5

It is in frankincense that the subsequent story of the rise and fall of the People of 'Ad would be written. The resin became an integral part of their lives over the next several millennia. Frankincense would beguile them. It would cause them to prosper and take on the airs of a classic civilization. And then, at least according to legend, the 'Ad became arrogant and unjust and were punished. Their desert city of Ubar was destroyed. At the same time, because of the rise of Christianity, the demand for frankincense fell off. And, whether or not they deserved God's wrath, the 'Ad would be left illiterate and poor, dwellers in the ruins of their past glory.

O

NE REASON

the People of 'Ad were so long cloaked in mystery is that outsiders were not welcome in their land; the harvesting of frankincense was a secretive affair. Nevertheless, Pliny the Elder managed to come by a good description of the process. Considerable pains were taken not to injure the trees, and timing was important. Only under the best conditions would the trees produce the finest, most fragrant incense. A midsummer harvest was augured by

...the rising of the Dog Star, a period when the heat is most intense; on which occasion they cut the tree where the bark appears to be the fullest of juice, and extremely thin, from being distended to the greatest extent. The incision thus made is gradually extended, but nothing is removed; the consequence of which is, that an unctuous foam oozes forth, which gradually coagulates and thickens ... this juice is received upon mats of palm-leaves ... The incense which has accumulated during the summer is gathered in the autumn: it is the purest of all, and is of a white color.

1

Around 3000

B.C.,

the range of the frankincense tree, encouraged by abundant rains, may well have extended out to and even beyond the spring at Shisur. In any case, the surrounding oasis was an ideal staging area for caravans heading north. It provided fodder for donkeys and dates for their drivers. Its palms shaded a primitive market, a place to barter for pack saddles, sacks of salt, obsidian tools, and luxuries like beads and decorative shells.

2

Forming at Shisur and striking north, the donkey caravans followed a trail of springs and seasonal lakes spaced no more than a day apart. Over the years, over the centuries, the footprints of thousands and thousands of animals compacted the desert pavement, creating a singular track, which at a later time would be called "the road to Ubar."

This great track led to Jabrin, a Mesopotamian-controlled oasis on the far northern edge of the Rub' al-Khali, where in all probability the People of'Ad sold (or bartered) their frankincense, then hastened home. Even though the climate was cooler than it is now and moist, the round trip was arduous. If a caravan failed to reach a spring or found it fouled or dry, animals and men could perish.

As they crossed the Rub' al-Khali, early caravans would have sighted a wild, humpbacked, ungainly animal that was at home in the desert wasteland. According to legend, the 'Adites thought it a creature conjured by djinns. But it would transform their lives. Over the previous centuries, man's livelihood in Arabia had benefited from the domestication of a sequence of animals: cattle provided mobility and sustenance, goats offered tents and textiles (as well as sustenance), and donkeys opened the way for long-range travel and trade. Finally, the camel was to make distant trade commercially viable year in and year out, in bountiful times and bad.

The camel could carry a six-hundred-pound load and could go two weeks or more without water. No longer was it necessary for caravans to meander from spring to spring; they could now move in straight lines. On level ground a camel caravan could cover thirty miles in a day. If need be, a well-bred camel could cover close to two hundred miles in a twenty-four-hour period.

Legendâand some evidenceâhas it that the camel was first domesticated in southern Arabia by the People of 'Ad. There, more than fifty "houses" (breeds) of camels were developed. The animals were cranky, had bad breath, and were certainly not beautiful in any conventional sense of the word. Yet their owners could gaze into a camel's great eyes and see both economic gain and a soulmate. In an age-old ditty of the desert, the beautyâand worthâof a woman is measured against the Banat Safar, a "house" of camels:

The fairness of beautiful girls

Is that of the Banat Safar.

Sa'id's daughter approaching a campfire

Is like a camel descending a difficult pass[i.e.: its head, like the girl's, turns superciliously from

side to side]Her fresh face is like a camel's flesh

Which the dew has not struck, nor the cold.

3

With the domestication of the camel, the pace of the incense trade quickened. Caravans could cross the Rub' al-Khali in less than a month, and their frankincense was then carried either north to Mesopotamia or west to the Red Sea. There it was loaded on boats bound for Egypt, where it was greatly valued as early as 2800

B.C.

As an offering worthy of "the great company of the gods," the Egyptian

Book of the Dead

considered incense far more than a ceremonial trapping: the incense itself was holy. At a funeral, the text instructed: "Thou shalt cast incense into the fire on

behalf

of Osiris" (rather than offer it

to

Osiris). Frankincense enhanced the afterlife journey of the deceased. In the words of the ritual

Pyramid Text,

"A stairway to the sky is set up for me that I may ascend on it to the sky, and I ascend on the smoke of the great censing."

4