The Rogue: Searching for the Real Sarah Palin (2 page)

Whew.

“And Catherine Taylor has been trying to reach you for months. She’d like to rent you the house she owns right next to Todd and Sarah.”

“I spoke to her yesterday. In fact, I’m meeting her at the house in half an hour.”

“Well, it’s practically falling down. It’s been vacant all winter. She used to have a bunch of ex-cons and drunks and drug addicts living there, supposedly trying to rehabilitate, although I don’t think most of them ever do. They were setting up a meth lab in the basement. Catherine had to call the troopers to get them out. And before that there was a woman living there whose fiancé’s son tried to kill her with a machete.”

“Sounds like she’s due for a tenant who won’t cause her any trouble.”

“I assured her you were mature and responsible and that you’d be a perfect neighbor for Todd and Sarah.”

I TURN LEFT at the stop sign at the entrance to the Best Western and drive down a rutted dirt lane. There are a couple of cabins in the woods on either side. In less than a hundred yards the lane ends at a clearing marked with

DO NOT ENTER

and

NO TRESPASSING

signs. There’s an abandoned delivery truck and three abandoned cars and an abandoned boat and three unused sheds in weeds at the edge of the clearing. The weeds stop at a ten-foot-high wooden fence, the uglier, back side facing Catherine Taylor’s property.

Close to the lake is a dilapidated ranch house that looks at least fifty years old. The wood siding has started to rot, some of the exterior glass is broken, and the steps leading up to the front door sag. The fence runs alongside the house, only six feet from it. On the other side, built smack-dab up against the fence, looms Todd and Sarah’s much newer, bigger house.

Catherine arrives twenty minutes late. She tells me she’s older than me, but I don’t believe it. She looks at least ten years younger, with dark hair and a dramatically expressive face. She carries herself like an actress and speaks in a manner that suggests familiarity with soliloquy. “I used to be quite photogenic,” she says. She’s so exuberant that I feel it’s only with difficulty that she’s resisting the impulse to reach out and pinch my cheek.

“What do you think?” she says.

“I think it’s right next door to Todd and Sarah.”

When I was in Wasilla last fall, I’d stopped by the Palin house to drop off a copy of

Going to Extremes

, my book about Alaska in the

1970s. I’d inscribed it, “To Sarah Palin—from one author who loves Alaska to another.” Track came to the door and we had a brief, pleasant chat as I gave him the book. “You wrote this? Wow! That’s awesome.” I told him I was glad he’d made it back safely from Iraq. He thanked me and said he’d give the book to his mother.

As we stand outside, Catherine, who lives in Settlers Bay, a residential enclave ten miles west of Wasilla, tells me she received title to this house, and to the vacant lot adjacent to it, in a divorce settlement with Clyde Boyer. Clyde is an accountant who was the father of five children before Catherine married him. They had no children of their own. He was chairman of the Mat-Su Valley hospital board when they illegally banned abortions. He took up with the marriage counselor Vivian Finlay after Vivian’s husband died of a stroke. Clyde and Vivian are now married and live in Homer.

You don’t simply conduct a business transaction in Wasilla, or anyplace else in Alaska. Even in preliminary discussion, you become a member of the other party’s extended family—more often families—to a degree that can leave you reeling from intimate information overload.

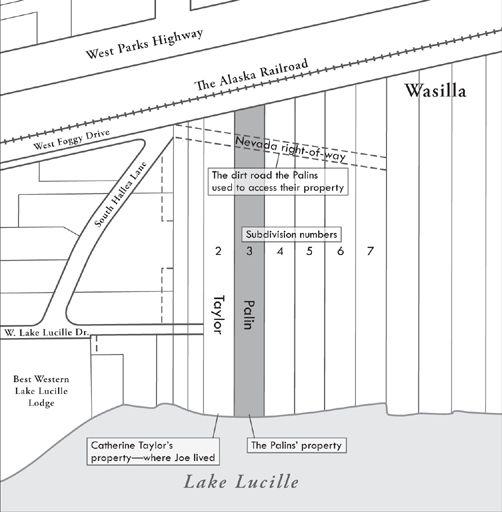

Catherine got the Lake Lucille house in 1997. It was surrounded by woods on both sides until the Palins built on the adjacent lot, which they bought after Sarah became mayor. The Palin lot was landlocked, meaning they had no vehicular access to it (see diagram, next page).

The seven two-acre lots in what is known as the Snider subdivision are long and narrow, offering a hundred feet of lake frontage and extending from the lake back almost to the railroad tracks. Catherine’s house is on Lot 2. The Palin property is Lot 3. West Lake Lucille Drive, the dirt road leading from the Best Western, provides road access to Catherine’s property. The private Nevada right-of-way that extends from South Hallea Lane to Lot 7 is where Charlie Nevada built the first house in the subdivision.

When you cross the railroad tracks on South Hallea Lane you immediately see a dirt track on the left with an old wooden sign that reads

NEVADA

. That’s the right-of-way that goes to Lot 7. It cuts across the back of Catherine Taylor’s property, providing the only land access to Lot 3. I used it in the fall when I dropped off a copy of my book at Sarah’s house.

The Palins had no road access to their new property, but Todd didn’t consider that a problem. Instead of asking for permission or offering a modest payment, he simply told Catherine that they’d be building next to her and cutting across her property in order to do so.

Catherine didn’t like being bullied. She told Todd he had no right to cut across her property to get to his own. Todd told her, very plainly,

that Sarah was mayor and they could do whatever they wanted, and it would be a mistake for her to try to stop them. Catherine called Sarah, who at least pretended to be more reasonable. Todd then called Catherine and said, “I don’t want you calling my wife again.”

“He was angry,” Catherine tells me. She recalls that he also said, “If you do anything to make it more difficult for me to build my house, I’m going to be very unhappy.”

She asked if he was threatening her. After a long pause, he said no, in a manner that did not convince her. It left her, in fact, with a “creepy, creepy, creepy feeling.” She went to her lawyer. Her lawyer said, “Todd’s right: Sarah is mayor. Do you really think you can fight city hall?”

So the Palins cut through her land without her permission in order to build their new home. They moved in during the summer of 2002. Todd had the house built to within ten feet of the property line, as close as he could get legally, and put up a ten-foot-high fence, the back side facing Catherine’s house, which is not the way good-neighbor Alaskans usually do it.

“They tortured that woman,” a friend of the Palins later told me. “I’d be with them when they were just laughing at her. I’d say, ‘Why are you being so mean?’ Sarah said, ‘Because we can.’ Todd said, ‘I want her to get the message: we’re here now.’ ”

Because she was already settled in Settlers Bay, Catherine never intended to live in the Lake Lucille house. Her first thought had been to use it as a shelter for battered women, but once Mayor Palin and her family moved next door she realized the house couldn’t be as private as such a shelter needed to be.

Instead, starting in 2005, she rented it to the Oxford House organization. Oxford House is a national network of group homes for recovering drug addicts and alcoholics, with particular emphasis on those who’ve just been released from prison. Their motto is “Self-Help for Sobriety Without Relapse.” The residents themselves run the

houses. There are more than six hundred Oxford Houses throughout the United States. Catherine’s was one of five in Alaska.

The Palins never complained about their neighbors. Neither Todd nor Sarah seemed bothered by having six ex-cons and recovering addicts living in such close proximity to them and their children. “Sarah was very pleasant to the men,” Catherine tells me. “She’d say hi when she was down at the lake, and sometimes she’d send over a plate of cookies.”

Catherine ran into problems in 2008, when the resident who’d been de facto manager of the house decided he was well enough to live on his own. Without his supervision, standards declined—to the point where two new arrivals began to build the meth lab in the basement, and Catherine had to call the state troopers to evict them.

And, yes, before that there was a woman named Elann “Lenny” Moren, whose fiancé’s son tried to kill her with a machete. The man did succeed in killing his father with the machete, and less than twenty-four hours later he killed a complete stranger in Anchorage before he was arrested, convicted, and sentenced to 498 years in prison. His name was Christopher Erin Rogers, Jr.

Because Lenny moved out before the Palins moved in, Todd and Sarah just missed having him for a neighbor.

ONCE INSIDE the house, I’m pleasantly surprised. Down a flight of stairs from the front entrance is a finished basement in need of attention, but on the main level the dining area, living room, kitchen, and bathroom have been newly renovated, with brand-new appliances and fixtures.

“Todd had this done last year,” Catherine tells me. “He and Sarah rented the house from May through October. He said he wanted to fix it up for a special guest who would be coming for an extended stay. Instead of paying rent, he renovated. I think Bristol and her baby were living here.

“In October, when he was supposed to start paying three thousand dollars a month, he left me a message saying the guest wasn’t coming and they didn’t need the house anymore. I said, ‘Todd, you’re leaving me in the lurch. There’s no way I can rent this house through the winter.’ He said, ‘Don’t worry about it, you’ll find someone.’ I said, ‘Yes, but I don’t want to rent to anyone you wouldn’t feel comfortable having next door.’ He said, ‘Don’t worry about it. That’s why we built the fence.’

“Colleen told me you were coming back,” Catherine says to me, “and I thought, ‘How perfect!’ I tried to reach you for months.”

“And now you have.”

“Well?”

“It’s more than perfect. But I can’t pay three thousand a month.”

“What can you pay?”

“Fifteen hundred? And only for the next few months. Once I’ve finished talking to people, I’ve got to go home and write.”

“It’s a deal.”

No need for any formalities, such as a lease. I write her a check and we seal the deal in the old-fashioned Alaskan way: with a hug.

“You’ve never been in prison, have you?” Catherine asks me as we walk back to our cars.

“Nope.”

“Have you ever been convicted of a felony?”

“Not yet.”

“In that case, you’ll be the first neighbor Todd and Sarah have ever had here who didn’t have a criminal record.”

MARNIE LOANS ME a duvet, and Tom puts some fresh-caught salmon and halibut into a cooler. I buy a Traeger grill. Traeger is an Oregon company that makes grills that use wood pellets instead of charcoal or gas. I’ve always been a charcoal man. I’d as soon cook indoors in

an electric oven as use a gas grill outside. On the other hand, I don’t want to burn down Catherine’s house by cooking with charcoal on a wooden deck. The Traeger seems to offer a path between the horns of my dilemma.

I buy the Traeger Junior, the smallest model, taking the one already assembled because I’d never have the patience or skill to put a grill together myself and I don’t want to have to ask my new neighbors to help me. It’s not polite to ask for a favor on the day you move in.

I head up the Parks Highway and get to the house in time to set up the grill and cook some of Tom’s salmon, which I eat on my deck overlooking the lake. It’s the best salmon I’ve ever eaten.

Except for a dining room table, four chairs, two plastic deck chairs, one horribly saggy mattress on a broken box spring, some old dishes, and a mix of plastic and metal utensils, Catherine’s house is unfurnished. If Bristol and her baby were living here, they were living rough.

But furnishings are a problem for tomorrow. Right now I’m still trying to come to terms with my amazing stroke of good fortune.

Admittedly, Lake Lucille is dead: not fit for either fishing or swimming. Even before Sarah became mayor in 1996, the lake was listed as “impaired” by the state Department of Environmental Conservation. The runaway growth Sarah encouraged during her six years in office worsened the problem. Leaching septic systems and fertilizer runoff, combined with pollution caused by the heavy automotive traffic through Wasilla, have killed off the fish population. “It’s basically just a runway for floatplanes,” one resident says.