The Root of Thought (16 page)

Read The Root of Thought Online

Authors: Andrew Koob

This might apply to adults as well. The growth of astrocytes in the brain might be evidence of an active brain—one always attentive, concentrating, pondering, considering, thinking, understanding. There is a reason Disney uses “Einstein” in its Baby Einstein products. It is because Einstein is synonymous with intelligence. If we think through recent history of someone who was constantly rattling his brain while trying to spring forth new ideas through imagination, we can easily agree that Albert Einstein fits this idea.

Einstein was notorious for his bouts of late-night mathematical study. His intense periods of thought resulted in the most astounding research in the area of physics in the history of mankind. He claimed that his brain was “his laboratory.” But what part of his brain?

His general theory of relativity states that time and space are one and they are relative. Einstein said that the happiest moment of his life was standing in an elevator and realizing if it fell out from underneath him, he wouldn’t feel his own weight. He understood that gravity was relative in our mind. This is the kind of man who used his glia.

Many dorm walls on college campuses display a poster of Einstein with the quote “Imagination is everything.” And Einstein meant an active imagination, using the brain to create something complete and not thought of before, and doing this with intense concentration. This might bring some enlightenment to the purpose of astrocytes in an evolutionarily sense.

The human experience is predicated on our ability to think of something new, using tools and ideas, to keep ourselves evolving. Biologically speaking, we have evolved to the point where we can create our own evolution. Other animals are always striving to this point, to make use of their environment to survive, but only humans have reached the evolutionary point where we can simply pick up something in our environment to create complex behavior. Our conscious thought to do this is believed to reside in the cortex. The astrocyte-neuron ratio increases in the cortex up the evolutionary ladder, the highest ratio in humans.

Einstein’s outward appearance was lush and rumpled like the countryside with its plush hills, creek ravines, and sugar trees sprouting in a mass of growth from glia seeds. However, his brain, like all humans, was his essence. His expression was as serene as a lake on a still June day, but his essence was as stark as a thunderstorm at night in May. He shuffled and stumbled through space like a chimpanzee, but his essence leaped like an Olympic athlete.

In the year of 1955, a wink from Einstein would be more powerful than a punch to the face from Rocky Marciano. But then he died. And his precious brain was no longer under his control. What happened is a bedtime story that all brain scientists know well. On April 17, 1955, Harry Zimmerman, the leading pathologist at Princeton University hospitals, couldn’t make it down from Philadelphia for the autopsy and had

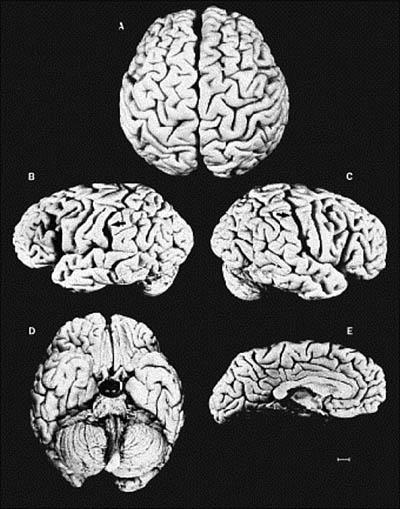

enough confidence in his understudy and former student at Yale Medical School, Thomas Harvey, to conduct it. Harvey sawed open the skull and plucked out the brain by cutting the cranial nerves, weighed it at 2.7 pounds, then plopped it in formaldehyde for preservation, finished up the autopsy (see

Figure 10.1

), and absconded with the brain out the door. Another doctor took off with the eyes.

FIGURE 10.1 Einstein’s brain in 1955 after autopsy.

Reprinted from

The Lancet

, Vol. 353, Issue 9170, Witelson, S.F., Kigar, D.L., and Harvey, T. “The Exceptional Brain of Albert Einstein,” p. 2151, Copyright (1999), with permission from Elsevier.

Harvey hung on to the brain in secret places at his home or kept it hidden in his office as the head of the university and Zimmerman demanded to know what he did with it. Harvey responded that he was preserving it for study. Their frustration grew by the day and by the year. In the meantime, Harvey had parts of it secretly sectioned into tiny slices by a lab technician, placed on slides and stained with cell-recognizing fluid similar to Golgi’s stain.

While Harvey was hiding away the brain, it must have held him in utter fascination. Imagine if you could put a piece of the sun in a jar. Imagine if you could see through Da Vinci or Van Gogh’s eyes and hear through Mozart’s ears. Or, in Harvey’s case, imagine if you had their eyes and ears in a box. Harvey must have wondered how the cogs and wheels in that pile of goo predicted that gravity would bend light. This was confirmed by Arthur Stanley Eddington (1882–1944) experimentally in 1919 during the total lunar eclipse. Einstein became an instant celebrity, even though his four seminal papers were published way back in 1905, the year before Cajal and Golgi’s standoff. Surprisingly, regarding all his theories and formulas, Einstein received his Nobel Prize in physics in 1921 not for relativity, but for the groundwork that led to the notion that light is both a wave and a particle. Harvey had the goop that conjured that, too.

Harvey had a piece of matter that completely captured out of the air a notion so important to humanity that it inspired every field of study. It was a brain that could routinely cook and stir and flip the unimaginable. From the 1930s on, Einstein focused on a theory that would unify everything—a theory that hasn’t come close to being solved—in addition to focusing on his nonscientific writings. In the late 1930s, his friend and former student Leo Szilard (1898–1964), who developed the nuclear chain reaction that made atomic weapons possible, came rushing out to the house where Einstein was summering in the Hamptons. Szilard was excited about the idea of how to create a super bomb, and he was terrified that the Germans might have also come up with a similar idea. He convinced Einstein to use his celebrity to write a letter to the president urging immediate research. They produced a letter to President Franklin Roosevelt, even as the government was investigating Einstein for unAmerican activities. Without the weight of his name behind the letter, the atomic bomb might never have been produced by the United States. However, Einstein claimed massive regret for signing the letter and sending it. The letter didn’t deter J. Edgar Hoover from being suspicious of Einstein.

Harvey had the piece of flesh that told Einstein’s neurons extending out to his hand to sign the document. Harvey might have pondered what in Einstein’s brain made the decision to sign and what in that brain considered the action a regret.

The brain that signed the letter, produced the concepts, and contributed to most of the impetus of major advance in the twentieth

century was still sitting in formaldehyde somewhere in Harvey’s possession at the time. However, the pressure at Princeton to give up the brain became too much and the administration forced Harvey out of the hospital.

Harvey took the brain with him to Missouri where he worked in family practice until he was found out and pursued by people who wanted a piece of the brain. He uprooted numerous times, and in the early 1990s, he was living in Lawrence, Kansas. However, when researchers requested sections of the brain, he usually complied.

In the early 1980s, Marian Diamond at U.C. Berkeley wrote to Harvey, requesting pieces of Einstein’s brain. A few months later, she received four pieces in a mayonnaise jar.

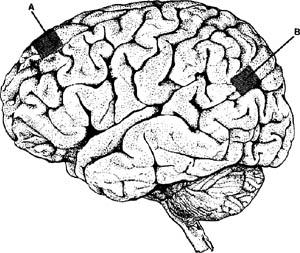

She compared them to 11 other similarly aged people who died from causes other than diseases or injury to the brain. Using a method called stereology, where researchers count cell averages at high magnification to extrapolate how many cells are in a given area of the brain, Diamond discovered that on average, Einstein had a higher astrocyte-to-neuron ratio in the area of the left parietal cortex called the angular gyrus, as shown in

Figure 10.2

. Einstein had so many more cells that it was “statistically significant,” a scientific term to mean that it was “pretty different enough to say that it means something.”

FIGURE 10.2 The area of Einstein’s brain with higher glia, the black square on the right.

Reprinted from

Experimental Neurology

, Vol. 88, Issue 1, Diamond, M.C., Scheibel, A.B., Murphy, G.M. and Harvey, T. “On the brain of a scientist: Albert Einstein,” p. 200, Copyright (1985), with permission from Elsevier.

It is possible that “applied thinking” or concentration and attention leads to astrogliogenesis and that the more astrocytes, the more ability for complex thinking. Einstein’s active concentration and utilizing his cortex while lost in thought might have created the growth of more astrocytes to increase his capacity for such complex thought. However, how much this was due to his innate ability or a genetic predisposition to astrocyte growth isn’t known. He, no doubt, had an intrinsic drive that gave him the ability to focus and think deeply. Einstein also had higher amounts of astrocytes in the right parietal cortex and in two areas of the front cortex. However, the only “significant” area was the left parietal cortex.

This area is believed to be responsible for higher thought, specifically related to language, mathematics, and spatial learning. Interestingly, Einstein’s parents had to take him to the doctor when he was three years old because of his late-developing speech.

Many more brains need to be studied to make a valid argument for an increase in glial cells to be responsible for more complex thought in the cortex. Eleven regular brains to one genius brain does not create the numbers scientists like to see when they are trying to find something statistically significant. However, how to acquire more brains of noted thinkers is obviously a problem to complete the study. Einstein was an obvious example. What about your next-door neighbor? Does he spend more time in active concentration and mentally strenuous activity as Einstein, but just doesn’t have the work to prove it? One does not necessarily need to be a celebrity to have an increased amount of mental activity.

Another problem is how much Einstein’s brain might have deteriorated in his old age. He seemed not to have dementia, but he wasn’t putting out papers describing the secrets of the universe anymore either. I’m sure getting someone like Bob Dylan’s brain might be interesting—for the area responsible for songs. Maybe it would have more glial cells. But by the time he dies, we don’t know what state his brain would be in, and researchers couldn’t really whack someone in their 30s like Jack White just to see if he has more glia, nor could they just wait behind the Nobel Prize podium with a hatchet and a bone saw and whack scientists after accepting the prize, and then compare the brain of the whacked person to 11 “regular people.”

Of course, the study into Einstein’s brain is flawed, not to mention that Harvey was ostracized by the scientific community and forced to keep the brain in mayonnaise jars. In the 1994 documentary

Einstein’s Brain

, by Kevin Hull, a Japanese professor of math and science history at Kinki University in Japan, Kenji Sugimoto, seeks out a piece of Einstein’s brain after he hears that it was preserved. He wants a piece for a souvenir and goes to great lengths to find Harvey. When he finds Harvey’s mentor Zimmerman, he claims Harvey is dead. But Sugimoto finds him alive living near William S. Burroughs in Lawrence, Kansas. Burroughs shows Sugimoto the movie

End of Days

, which begins with Lawrence being wiped off the map by an atomic bomb. He gives directions on how Sugimoto can find Harvey, “Go along the river there. And you come to where the old cemetery used to be. That was dug up and converted into a trailer court. The trailer court was subsequently completely destroyed in the ’81 tornado. Some said it was the judgment of the dead for being disturbed. But at any rate, there you turn left and you’ll come to Stranger’s Creek. Harvey…Dr. Harvey’s house is just on the other side of the creek.”

Burroughs knows something about keeping an active mind into a late age.

Harvey is surreptitious about the brain, not revealing many secrets and unsure what to think of Sugimoto. Eventually, he brings the brain out in a sugar jar with a clasp top. Sugimoto asks if he might have a piece. Harvey hems, haws, and then gives him a section. Sugimoto asks again if he might have not a section but an actual piece. Harvey laughs and realizes his motives are genuine and relents. Harvey then ambles over to the kitchen and grabs a butcher knife and cutting board, pulls a piece of the

brain stem and cerebellum out of a cookie jar, likely choosing the cerebellum for its lack of interest. (The cerebellum is the back of the brain and thought to be for controlling our joints and motor coordination so we can move in 3D space. An animal with a removed cerebellum walks around like a drunk. It is an obscenely understudied part of the brain and likely not an area Harvey would receive many requests for.) He chops off a piece of the cerebellum like he’s cutting an onion and hands it to Sugimoto in a prescription pill container. In the end, we learn Harvey is working as an extruder apprentice and is employee of the month at the factory.