The Seance (33 page)

Professor Ernest Dingwall, Mr John Barrett, FRS and Dr Francis Iremonger were called to testify on this point. The effects of being struck by lightning in the open – there appeared to be no precedent for the manner of Magnus’s death – varied considerably. Some had survived, with burns of varying degrees; in one case a man was rendered unconscious, and when he recovered, walked away from the scene with no recollection of having been struck. Others had died instantly; one victim’s skull had been reduced to fine fragments, with no apparent injury to the skin. No one could cite anything like the annihilation of Dr Wraxford, but Mr Barrett gave it as his opinion that the force of the bolt could have been greatly concentrated by the armour. Dr Iremonger took a diametrically opposite view, maintaining that the suit of armour would have acted as a ‘Faraday cage’ – i.e., the entire force of the blast would travel around the outside of the suit, leaving the person inside unharmed.

The coroner inquired, with a good deal of sarcasm, whether the learned gentleman would care to try the experiment himself. The learned gentleman confessed that he would not.

It was clear, from that moment onward, that the coroner had made up his mind that Nell Wraxford was guilty. He remarked in his summing-up to the jury that ‘the lightning strike upon the Hall was mere chance, and very long odds at that, the salient point being that if Magnus Wraxford was not already dead when his murderer forced him into the armour at gunpoint – Mr Montague’s testimony alone

seems to me decisive upon this point, though of course you must make up your own minds – if, as I say, Magnus Wraxford was not already dead, he had been left there to starve. You may well consider, gentlemen of the jury, that jamming the mechanism was as culpable, and far crueller, an act of murder than shooting him dead would have been.

‘Furthermore,’ he continued, ‘an infant child is missing in circumstances which can only point to the mother’s guilt. Why would Mrs Wraxford not allow anyone else near her child? You may well conclude, gentlemen, that her insistence on caring for the infant alone is already evidence of unsound mind. You have Dr Rhys’s testimony as to her extreme agitation on the night of Mrs Bryant’s death; the curious fact of her being the only person, on her own account, not to be woken by that lady’s death-cry, which was heard two hundred yards away. You have heard, too, that a crumpled note was found by the police on the floor of Mrs Bryant’s room – a note inviting her to come to the gallery at midnight – which is when and where she died. The hand appears to be that of Mrs Wraxford. We are not charged with investigating this death, but it is suggestive, all the same, of a dangerous predisposition to violence on Mrs Wraxford’s part.

‘Then there is the matter of the necklace. You have heard from Dr Rhys that Mrs Wraxford appeared to be deeply estranged from the deceased. You have heard, from the representative of the Bond Street firm who furnished the necklace, that the deceased purchased this very extravagant gift for his wife for the sum of ten thousand pounds – which suggests an uxorious, even infatuated husband willing to go to the most extravagant lengths to win back his wife’s regard. You have heard that the empty jewel-case was found by the police beneath a floorboard in Mrs Wraxford’s room. The necklace is nowhere to be found.’

He said a great deal more in the same vein. After brief deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of wilful murder by person or persons

unknown, and a warrant was immediately sworn for Eleanor Wraxford’s arrest.

The post-mortem on Mrs Bryant revealed that she had indeed been suffering from advanced heart disease and had died of heart failure, probably as a result of a severe shock. But the family were not satisfied; the estranged son now became the mother’s champion, and rumours then began to circulate in London to the effect that Dr Rhys and the Wraxfords had conspired to murder her – and that Eleanor Wraxford had then disposed of her husband and child and fled with the diamonds.

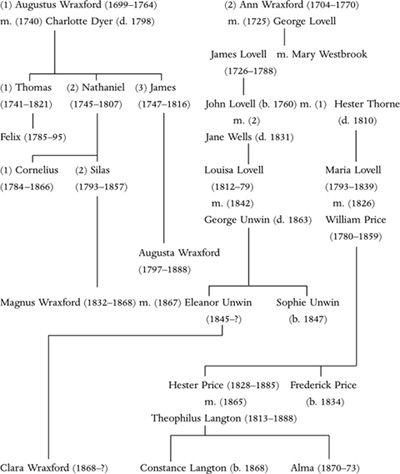

Magnus Wraxford, in a will dated some months before his death, had left his entire estate to his cousin Augusta Wraxford, a spinster nearly forty years older than himself, making no provision for Nell or Clara, or any of his servants. Mr Veitch wrote to me in the most cordial terms to make certain that Magnus had not left any later will with me. The estate, however, consisted entirely of debts: the contents of the Munster Square house had to be sold to reduce them; and at the end of the proceedings the servants (with the exception of Bolton, from whom I never heard again) were thrown on to the street to look for new situations. The bequest to Augusta Wraxford – who had, as I would later learn, nurtured a lifelong resentment against her male relations for bringing ruin upon the estate – seemed like a satiric act of malice.

I continued to act as solicitor to the estate, partly out of fear of what someone else might discover, and partly in the vain hope of hearing some news of Nell. Augusta Wraxford – a fierce old lady of decidedly eccentric views – came to see me as soon as Magnus’s will had been proven, and instructed me to locate her nearest female relative. Thus began the long and weary process of constructing and testing a

genealogy, in the course of which I discovered that Nell had been distantly related to Magnus, though neither appeared to have known, which made the tragedy seem even darker. And though Augusta Wraxford had long coveted the Hall, she could not afford to render it habitable; the most she could do was to reduce the burden of debt. But neither was she willing to sell, and so the house was once again closed up, and left to its long decay.

My confession is done. It has tormented me day and night, not knowing what to believe. When I summon Nell’s face, I cannot imagine her a murderess. But then I think of the evidence, and am confronted once again with what I know would be the world’s verdict: that she deceived me utterly, and made me, through my own foolish infatuation, an accessory to murder.

WRAXFORD GENEALOGY AS COMPILED BY JOHN MONTAGUE

ll day while I read the rain fell steadily, splashing on the gravel beneath the sitting-room window and lying in pools upon the sodden grass. Except for an occasional glimpse of bare branches gliding through the mist, there was nothing to be seen beyond the top of the wall but grey, swirling vapour; I looked up more than once from the pages of John Montague’s narrative and felt the hair rise on the back of my neck before the warmth of the fire brought me back to Elsworthy Walk.

ll day while I read the rain fell steadily, splashing on the gravel beneath the sitting-room window and lying in pools upon the sodden grass. Except for an occasional glimpse of bare branches gliding through the mist, there was nothing to be seen beyond the top of the wall but grey, swirling vapour; I looked up more than once from the pages of John Montague’s narrative and felt the hair rise on the back of my neck before the warmth of the fire brought me back to Elsworthy Walk.

I knew, long before I reached the end, that it could only be my resemblance to Nell that had so shaken him; that, and the wild fancy, as he had put it, that I might be Clara Wraxford. My heart had accepted – indeed seized upon – the possibility before my head had even begun to comprehend what it might mean, beyond the conviction that Nell could never have harmed her child. There were so many questions I wanted to ask Mr Montague, and yet there was a strange finality about his letter, a note of farewell, as if he did not expect to hear from me again.

My uncle (rather to my relief, for I could not decide how much, if anything, I ought to tell him) had decided to brave the weather in order to dine with some artist acquaintances, and so I took my supper on a tray by the fireside while studying the genealogy that John Montague had compiled. A wind had risen and was rattling the casements, sending gusts of rain lashing against the glass.

The chart had been drawn so that Clara Wraxford (1868–?) and Constance Langton (b. 1868) were side by side at the foot of the page. All my life I had thought of myself as separate, cut off from the rest of the world. Dr Donne’s saying that ‘No man is an Island’ had always inspired in me the opposite sentiment; our house in Holborn

had

been, sadly, an island, entire unto itself, and Alma’s death had diminished us all the more because of it. To many, I suppose, the Wraxford connection would have seemed profoundly undesirable, but for all its dark and sinister history, my world felt suddenly enlarged.

Supposing, I thought, staring at the faint tracery of lines connecting us, just supposing I

am

Clara Wraxford: what would follow from that? First, that Nell was innocent of the worst of the crimes laid at her door – but her journal alone was proof enough for me, just as I felt certain she had had nothing to do with Mrs Bryant’s death. And if she really had shut Magnus in the armour, she had done it in fear of her life – and Clara’s. I wondered if Mr Montague had made a grave mistake in not handing those journals to the police.

But if, on the other hand, John Montague had chosen to conceal not only the package he had found in Magnus’s greatcoat pocket, but the dagger, the pistol, and the fragment of cloth, Magnus’s death would have been judged an accident, the result of a bizarre experiment – a phrase he himself had used in speaking of his uncle Cornelius – and then, if Nell

had

escaped with Clara, there would have been no need for her to hide, once the news was out.

What had happened on the night of Mrs Bryant’s death? Nell had said, in her last entry, that she meant to watch from the library and find out

who had summoned her. Perhaps in the end she had thought better of it; perhaps she really had been asleep when the maid knocked at her door with news of Mrs Bryant’s death. And then, some time later that night, she and Clara had disappeared from the room.

I would not, I told myself sternly, allow my mind to dwell upon phrases such as

carried off body and soul

.

And of course Nell had not been carried off, because Magnus had seen her – or said he had seen her – on the stair, after everyone else had left the Hall.

But if Nell had trapped him in the armour (and I could not, in my heart of hearts, really believe otherwise) she must have returned to the house after everyone else had left; or else she had been hiding there all the time. Alone, she might have evaded the search; but not if she had been carrying Clara. And if she had left the Hall early that morning, she would never have brought Clara back.

Especially not if she had planned to escape all along. Suppose she had arranged for someone to meet her at dawn – a few hundred yards along the path, perhaps – and drive her and Clara to safety? Suppose, in other words, that Mrs Bryant’s death had been, from Nell’s point of view, a ghastly coincidence, and that she had never intended to be at the séance at all?

But why, with freedom so close, would she ever have returned to the Hall?

Because she had forgotten her journal

. Even as the words formed themselves in my mind, I saw how it must have been: lying awake through the small hours, waiting fearfully for the first glimmer of dawn (she would not have dared show a light), dressing hastily – no, she would have been fully dressed already – gathering up her sleeping child, still drugged by the laudanum – then locking the door behind her, in terror lest the snap of the lock give her away, but knowing it would give her more time to get away from the Hall. No wonder she had left her journal behind; the only mystery was why she had risked going back for it.