The Second World War (94 page)

Intrigues even more intense than those within Allied Force Headquarters seethed within the French colonial quarter of Algiers. Ever since the shotgun marriage of General Henri Giraud and General Charles de Gaulle, enforced by Roosevelt and Churchill at Casablanca in January, the Gaullists had been awaiting their moment. On 10 May, the third anniversary of the German invasion of France, the Conseil National de la Résistance in occupied France acknowledged de Gaulle’s leadership. Neither Roosevelt nor Churchill had any idea how significant this would prove to be.

On 30 May, General de Gaulle finally arrived in Algiers at Maison Blanche airfield, having been long delayed by the American military authorities at Roosevelt’s instigation. In the blinding sunlight a band played the ‘Marseillaise’, while British and American officers tried to stay in the background. They had good reason to try to keep out of things. The day before, Giraud had decorated Eisenhower with the medal of Grand Commander of the Legion of Honour, but de Gaulle, as Brooke found, was ‘

indignant that Giraud

should have done this without consulting him!’

The key to power was control of the Armée d’Afrique, which was starting to be rearmed with American equipment and weapons. Inevitably, deep suspicions lingered between the traditional officers, or

moustachis

, of

the former Vichy army which had been loyal to Pétain, and the

hadjis

, so-called because they had made the pilgrimage to London to join de Gaulle. The imbalance in numbers was considerable. The

moustachis

commanded 230,000 troops, while the Free French from the Middle East and Koenig’s force which had so distinguished itself at Bir Hakeim had only 15,000 men. The Gaullists began poaching troops for their own formations, which caused Giraudist outrage. But de Gaulle’s moral authority and superior political skills would bring him out on top.

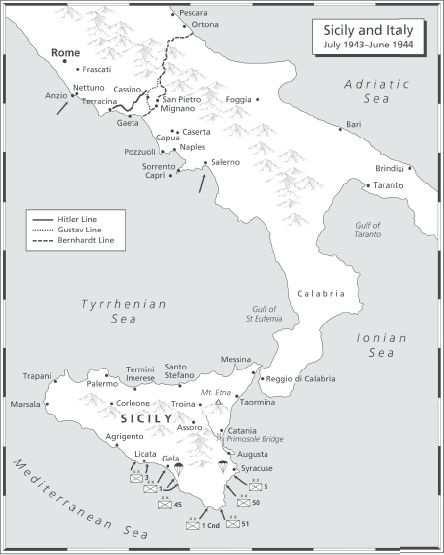

On 10 July Husky began with pre-dawn airdrops, then 2,600 ships landed with eight divisions, as many as in Normandy eleven months later. By nightfall the Allies had 80,000 men, 3,000 vehicles, 300 tanks and 900 guns ashore.

The Germans were taken by surprise. Operation Mincemeat, dropping the body supposedly of a Royal Marine officer with fake plans off the Spanish coast, together with other deception plans had misled Hitler into believing that the invasion was aimed at Sardinia and Greece. Generalfeldmarschall Kesselring still believed that Sicily or southern Italy were more likely objectives, but he was overruled. Mussolini had reinforced Sardinia, convinced that the Allies would land there after their bombing attacks on the island. There had also been strikes and unrest in Turin and Milan, which increased the Fascist regime’s nervousness.

The sea had been calm when the invasion fleets set sail, but soon strong winds churned it up and the ships wallowed, provoking seasickness among the troops packed aboard. Those on a flat-bottomed LST, or Landing Ship Tank, suffered the worst, rolling and lurching in every direction. Fortunately the winds eased as they approached the coast. Montgomery’s Eighth Army headed in to the south-eastern tip of the Sicilian triangle. His forces would then strike north up the coast towards Messina to cut off the Axis divisions before they could cross back to the mainland. Patton’s US Seventh Army was landing to the west at three points on the southern coast, also guided in by Royal Navy submarines acting as beacons, flashing blue lights out to sea. Once ashore, no clear objectives had been set for the Seventh Army, a vagueness in planning which Patton had every intention of exploiting.

Shortly before 02.00 hours on 10 July, the order was given–‘Lower away!’–and the landing craft were winched down from davits into the water. The sea was still rough, and soon soldiers were sliding about on the vomit of the sufferers. Eventually, the assault craft were launched, and a correspondent watched the ‘

hordes of tiny craft

, like water bugs, scooting towards the shore’. The landing was far from easy in heavy surf, and with minefields on the beaches. Often troops came ashore at the wrong place, and the confusion was at times almost as bad as during Operation Torch. Within a few hours the amphibious DUKWs went into action, bringing in supplies, fuel and even batteries of artillery.

Inland, the airborne landings in the high winds had been chaotic, with paratroopers from both the British 1st Airborne Division and the US 82nd Airborne scattered all over the place. Many suffered leg injuries. The British glider force, whose objective was a key bridge just south of Syracuse called the Ponte Grande, suffered the most. The tug pilots had little experience, and their navigation was dreadful. One glider landed in Malta and

another near Mareth in southern Tunisia. Sixty gliders released too early crashed in the sea. But the thirty men who made it to the target still managed to seize the bridge, and remove the demolition charges. They were joined by another fifty men during the morning and held it against heavy attacks for most of the afternoon, until only fifteen were left unwounded. Although they were forced to surrender, the bridge was swiftly retaken by the Royal Scots Fusiliers arriving from the beach. The whole operation had cost 600 casualties, of whom almost half had drowned.

Whatever the confusion on the Allied side, the 300,000-strong Axis forces were in greater disarray. The storm at sea had convinced them that there could be no invasion that night. General Alfredo Guzzoni’s Sixth Army may have been 300,000 strong in theory, but it contained just two German divisions, the 15th Panzergrenadiers and the

Hermann Göring

Panzer Division. The former had been deployed in the west of the island and was too far away to counter-attack, so Kesselring ordered the

Hermann Göring

to advance immediately on Gela, which had been captured by Rangers in Patton’s central landing on the first day. The 1st Infantry Division, ‘the Big Red One’, had then moved inland to occupy the high ground and take the local airfield.

The attack of the

Hermann Göring

on the morning of 11 July caught the leading infantry battalions without tank support. The Shermans had not yet been landed. To the west, the Italian Livorno Division also advanced on Gela, but was soon halted by mortars firing white phosphorus, directed in person by General Patton, and naval gunfire from two offshore cruisers and four destroyers. The

Hermann Göring

to the north and north-east of the town almost reached the beaches. Their commander even informed General Guzzoni that the Americans were re-embarking. Just in time, a platoon of Shermans and some artillery were landed. The 155mm ‘Long Toms’ went straight into action, firing over open sights.

In a vineyard below Biazza Ridge to the east, part of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment under Colonel James M. Gavin came up against Tiger tanks attached to the

Hermann Göring

Division. Gavin had no doubts about the aggressiveness of his men who, before leaving Algeria, had practised their marksmanship on ‘

some menacing looking Arabs

’. But against the Tigers they had only bazookas and a couple of 75mm pack guns.

Fortunately for the paratroopers, a naval ensign with a radio volunteered to called down naval gunfire. Gavin was understandably nervous, wondering how accurate it might be. He asked for a single ranging shot first. It was right on target. He called for a concentration. The Germans began to pull back, and then the first Sherman tanks arrived from the beach, to the cheers of the paratroopers. Together they attacked the ridge and managed to kill a Tiger crew unwisely standing outside their tank, which they

captured. They looked at the bazooka strikes on the front of the Tiger, and saw that they barely dented its massive frontal armour. The

Hermann Göring

panzers had to withdraw rapidly right along the front, fired at all the time by the US Navy. Patton, who had been cheering and cursing on his troops around Gela, was well satisfied. ‘

God certainly

watched over me today,’ he wrote in his diary.

During the night, Patton’s mood changed again. The 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment was due to fly in from Tunisia in the early hours and drop behind Seventh Army lines as an instant reinforcement. He wanted to cancel the operation, but found that it was too late. He suspected that his order to anti-aircraft gunners ashore and on land to hold their fire had not been disseminated properly. The guncrews could not distinguish between friend and foe, especially in the dark, and were jumpy after all the Luftwaffe attacks that day. Landing force commanders complained about the lack of Allied air cover over the beaches, but their air force colleagues remained reluctant to risk their fighters when Allied anti-aircraft gunners fired at anything that flew.

Patton’s worst fears were realized. A single machine gun began firing when the C-47s appeared, and then everyone joined in, even tank gunners with their turret-mounted .50s. His men simply could not stop themselves. They continued firing at the paratroopers coming down and even after they hit the ground or the water. It was one of the worst examples of ‘friendly fire’ on the Allied side in the war, with twenty-three planes destroyed, thirty-seven badly damaged and over 400 casualties. Eisenhower, when he eventually found out, was furious and blamed Patton.

Patton’s position, however, was eased when General Guzzoni ordered the

Hermann Göring

to move east to block the Eighth Army on the road north to Messina. The British had taken Syracuse against the lightest resistance. But over the next few days, as they advanced up the coast road towards Catania, the fighting became far harder. The Germans were in the process of reinforcing the island with the 29th Panzergrenadiers and the 1st Fallschirmjäger Division of paratroopers. General Hube’s XIV Panzer Corps headquarters had been flown in to direct Wehrmacht troops. But Hube’s principal objective, agreed with Guzzoni, was to fight a holding action to protect Messina and the straits, so that their forces could be withdrawn to the mainland to avoid another surrender like the one at Tunis.

On 13 July the British attempted another parachute drop, this time to capture the Primosole Bridge near Catania. Once again the aircraft were fired on by the invasion fleet as well as by Axis anti-aircraft guns, causing chaos. Out of the 1,856 men of the 1st Parachute Brigade, fewer than 300 reached the rendezvous point near the bridge. They secured it by the following morning and removed the demolition charges. Counter-attacks by

the recently arrived 4th Fallschirmjäger Regiment almost drove them off, but despite losing a third of their strength, the British paratroopers just managed to hold on.

The 151st Brigade, with three battalions of the Durham Light Infantry, was coming to their relief on a forty-kilometre forced march in full kit in temperatures of 35 degrees Centigrade. On the way they were strafed by German fighters and bombed by American aircraft. The 9th Battalion of the Durhams went straight into the attack, suffering heavy losses from well-camouflaged German paratroopers firing low with their MG 42s, which the British called Spandaus. ‘

From the high ground

where we watched the 9th Battalion make their frontal assault,’ wrote a Durham, ‘the sight was shocking. The River Simeto did, literally, run red with the blood of the 9th Battalion. It was all over by 09.30 hours. They had succeeded in preventing the Germans from blowing up the bridge.’

Another battalion of the Durhams managed to ford the river later and take the Germans by surprise, but the bitter battle continued. The Durhams claimed that German snipers shot down their stretcher-bearers as they collected the wounded. As the battalion ran out of ammunition, Brengun carriers shuttled back and forth to replenish them. The smell of dead bodies in the heat prompted the carrier drivers to name the spot ‘stink alley’. But finally the German paratroopers were forced back when the 4th Armoured Brigade arrived.

While the battle for the Primosole Bridge went on, the 51st Highland Division to the west attacked Francoforte, a typical Sicilian hilltop village above terraces of olive groves, reached only by a dirt road twisting up the steep slope in hairpin bends. To their left another part of the division managed to take Vizzini, after another short, fierce action. The Jocks of the Highland Division pushed on full of confidence. But they were soon to receive a nasty shock at Gerbini, where the Germans put up a strong defence at the adjoining airfield. The

Hermann Göring

and the Fall-schirmjäger Division deployed their 88mm anti-tank guns with devastating effect. The British XIII Corps on the coastal plain was blocked, while XXX Corps had to fight from ridge to ridge. British soldiers hated fighting in the rocky hills of Sicily and began to feel nostalgic for the North African desert.

Montgomery decided to move his XXX Corps over into Patton’s zone, so that it could attack around the western side of Mount Etna. Alexander agreed to this without first consulting Patton, who was understandably riled. Major General Omar Bradley, the commander of II Corps, was even angrier and told Patton that he should not allow the British to do that to him. But Patton, after Eisenhower’s explosion over the airborne disaster and the lack of information he received from Seventh Army headquarters,

did not want another battle with a superior officer. Bradley could hardly believe that Patton would be so docile.