The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (70 page)

Read The Secret Life of Salvador Dali Online

Authors: Salvador Dali

My fear of being afraid had by now become a single very precise fear—that of going mad and dying! One of Lydia’s sons died of hunger. Immediately I became a prey to the fear of not being able to swallow my food. One evening it happened: I could no longer swallow! I hardly slept at night any longer, and during the long hours of darkness my anguish did not relinquish its grip on me for a single moment. In the daytime I would run out abjectly and sit with the fishermen who came to chat in a spot sheltered from the wind and warmed by the sun, out of the

tramontana

1

which did not relax its unleashed violence. The talk about the troubles and hardships that were the daily lot of the fishermen succeeded in distracting me a little from my obsessions. I would ask them questions of all sorts, for I should have liked to tear from them living bits of their own anguish to be able to hold them up against my own. But they were not anguished; they were not afraid of death. “We,” they said, “are already more than half dead, you might say.” One of them would sit and slowly cut away with a fish-knife pieces of dead skin from the yellow thickness under his feet, another would pick off scabs covering the backs of his hands where the blue veins swollen by arteriosclerosis followed their hardening course between the hair bristles. Bits of scabs would cling to these hairs, and sometimes a gust of wind would blow some of these over the copy of

Vogue

magazine that I was thumbing through. Gala would come eagerly running with the bundles of American and Parisian magazines which she knew sometimes distracted me for brief moments. There was a photograph of an ultra-sophisticate wearing jewel clips combined with flowers—she had appeared at a garden party wearing a diamond in the shape of a large drop of water dripping from a natural rose. There was an advertisement of a new lipstick which was said to be the real Dali red, which had to be applied over two liquid layers.

Batu, the old fisherman, would break wind in slow, deliberate blasts, after which he exclaimed, “I’m not going to eat any more octopus; my wife she has a whorish mania for putting too much garlic in it, and then I get belly-gripes!” “That isn’t it,” another fisherman answered,

“it’s the beans you ate two days ago. Beans can make you f—t two days after.”

At the stroke of noon the beating sun would kindle the slumbering fire of everyone’s hunger. I would send for a few bottles of champagne that we drank to wash down a mess of sea-urchins. We were in for three more days of wind!

“Gala, come here, bring me the cushion, and hold my hand tight; I think I’ll go to sleep. I feel less anguish. It’s pleasant here now.”

A small lizard with a quick-moving head and a triangular face darted alertly to catch a fly absorbed in sucking the juice from a crushed sea-urchin. But a gust of wind blew over a page of one of my magazines, making him scurry back under a crevice of the dilapidated wall from which he had crept. Around me I felt the conversations of the fishermen gradually die down. Dragging the weight of the voluptuous chains of digestion they were falling off one by one into dreams. We were all sheltered as if in the furnace of the afternoon, and the furious whistling of the wind which could not reach us was all the more agreeable. And this whole conglomeration of poor fishermen with clothes woven of patches, with Homeric souls and with essential odors would mingle as I sensed the approach of sleep, so painfully desired, in a blend of “reality” which in the end outweighed that of my anguish and of my imagination.

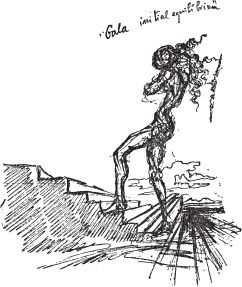

When I awoke, all the fishermen had left; the wind had stopped blowing, and Gala

2

was bowed over my slumber, like the divine animal of anxiety over the body of the “chrysalis Lazarus” that I was. For like a chrysalis, I had wrapped myself in the silk shroud of my imagination,

and this had to be pierced and torn to enable the paranoiac butterfly of my spirit to emerge, transformed—living and real. My “prisons” were the condition of my metamorphosis, but without Gala they threatened to become my coffins, and again it was Gala who with her very teeth came to tear away the wrappings patiently woven by the secretion of my anguish, and within which I was beginning to decompose.

“Arise and walk!”

I obeyed her. For the first time I experienced the “savor” of tradition upon feeling myself touching the earth with the soles of my feet.

“You have accomplished nothing yet! It is not time for you to die!”

My surrealist glory was worthless. I must incorporate surrealism in tradition. My imagination must become classic again. I had before me a work to accomplish for which the rest of my life would not suffice. Gala made me believe in this mission. Instead of stagnating in the anecdotic mirage of my success, I had now to begin to fight for a thing that was “important.” This important thing was to render the experience of my life “classic,” to endow it with a form, a cosmogony, a synthesis, an architecture of eternity.

1

The spells of the

tramontana

last sometimes for three weeks uninterruptedly, during which the sky is always serene, but the fishermen cannot put out to sea.

2

Once already Gala Gradiva had cured me of madness with the corporeal reality of her love. Having become practical, I had been able to achieve my surrealist “glory.” But this success threatened a relapse into madness, for I was shutting myself up in the world of my realized image. It was necessary to break this cocoon. It was necessary for me really to believe in my work, in its importance outside of myself! She had taught me to walk; I had to advance like a Gradiva, in my turn. I had to pierce the cocoon of my anguish. Mad or living! I have said again and again: living, aging until death, the sole difference between myself and a madman is the fact that I am not mad!

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

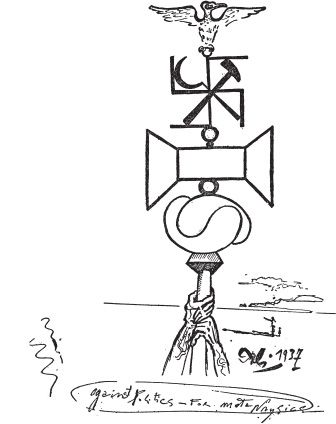

Metamorphosis Death Resurrection

Dingdong, Dingdong, Dingdong, Dingdong . . .

What is it?

It is the clock of history that has rung.

What does the clock of history say, Gala?

On the dial of the clock of history, after the quarter-hour of the “isms,”

1

the hour of the individual is about to sound! Your hour, Salvador!

Dingdong, dingdong, dingdong, dingdong! Post-war Europe was about to croak of the anarchy of “isms”; of the absence of political, esthetic, ideological and moral rigor. Europe was about to croak of scepticism, arbitrariness, drabness, lack of form, lack of synthesis, lack of cosmogony. Post-war Europe was about to croak of lack of faith. It thought it knew everything from having tasted the forbidden fruit of specialization. But it believed in nothing and trusted in everything, even in morality and esthetics, in the anonymous flaccidity of the “Collective.”

Excrements always depend more or less on what one has eaten. Postwar Europe had continually eaten “isms” and revolution. Its excrements

would henceforth be war and death. The collective sufferings of the war of 1914 had led to the childish illusion of “collective well-being” based on the revolutionary abolition of all constraints. What had been forgotten was the morphological truth that is the very condition of wellbeing, which can only be ultra-individualistic and built on the rigor of hyper-individualistic laws and constraints, capable of producing a “form of reaction” original and peculiar to each spirit. Oh, the spiritual poverty of the Post-War era, the poverty of individual formlessness swallowed up in the formlessness of the masses! The poverty of a civilization which, avowedly destroying every kind of constraint, becomes the slave of the scepticism of its new liberty, constrained to the most practical and the basest necessities, those of the mechanical and industrial type! The poverty of a period that replaces the divine luxury of architecture, the highest crystallization of the material liberty of intelligence, by “engineering,” the most degrading product of necessity! The poverty of a period which has replaced the unique liberty of faith by the tyranny of monetary utopias! . . . The responsibility for the war which was to break out would lie solely on the ideological poverty, the spiritual famine of this Post-War period, which had mortgaged all its hope on bankrupt materialistic and mechanical speculations.

For there is no materialistic thought that is not basely mechanical; and even the dialectic of Engels has only a metaphysical value. There can be no intellectual greatness outside the tragic and transcendental sense of life: religion. Karl Marx wrote, “Religion is the opium of the people.” But history would demonstrate that his materialism would be the poison of “concentrated hatred” on which the people would really croak, suffocated in the sordid, stinking, and bombarded subways of modern life. Whereas “the religious illusion” had made the contemporaries of Leonardo, of Raphael and of Mozart thrill beneath the perfection of the architectonic and divine cupolas of the human soul!

Gala was beginning to interest me in a voyage to Italy. The architecture of the Renaissance, Palladio and Bramante impressed me more and more as being the startling and perfect achievement of the human spirit in the realm of esthetics, and I was beginning to feel the desire to go and see and touch these unique phenomena, these products of materialized intelligence that were concrete, measurable and supremely non-necessary. Also, Gala had decided to undertake some further building in our little house in Port Lligat—a new floor. She knew that this would distract me from my spells of anguish, and would canalize my attention on small immediate problems.

From day to day Gala was reviving my faith in myself. I would say, “It is impossible, even astrologically, to learn again, like the ancients, all the vestiges of technique that have disappeared. I no longer have time even to learn how to draw as they did before! I could never improve on the technique of a Boecklin!” Gala demonstrated to me by a thousand inspired arguments, burning with faith, that I could become something

other than “the most famous surrealist” that I was. We were consumed with admiration over reproductions of Raphael. There one could find everything—everything that we surrealists have invented constituted in Raphael only a tiny fragment of his latent but conscious content of unsuspected, hidden and manifest things. But all this was so complete, so synthetic, so “one,” that for this very reason he eludes our contemporaries. The analytical and mechanical short-sightedness of the Post-War period had in fact specialized in the thousand parts of which all “classic work” is composed, making of each part analyzed an end in itself which was erected as a banner to the exclusion of all the rest, and which was blasted forth like a cannon-shot.

2

War had transformed men into savages. Their sensibility had become degraded. One could see only things that were terribly enlarged and unbalanced. After a long diet of nitro-glycerine, everything that did not explode went unperceived. The metaphysical melancholy inherent in perspective could be understood only in the pamphleteering schemata of Chirico, when in reality this same sentiment was present, among a thousand other things, in Perugino, Raphael or Piero della Francesca. And in these painters, among a thousand other things, there were also

to be found the problems of composition raised by cubism, etc., etc.; and from the point of view of sentiment—the sense of death, the sense of the libido materialized in each colored fragment, the sense of the instantaneity of the moral “commonplace”—what could one invent that Vermeer of Delft had not already lived with an optical hyper-lucidity exceeding in objective poetry, in felt originality, the gigantic and metaphorical labor of all the poets combined! To be classic meant that there must be so much of “everything,” and of everything so perfectly in place and hierarchically organized, that the infinite parts of the work would be all the less visible. Classicism thus meant integration, synthesis, cosmogony, faith, instead of fragmentation, experimentation, scepticism.