The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (73 page)

Read The Secret Life of Salvador Dali Online

Authors: Salvador Dali

Then I looked her straight in the eye and scrutinized her closely, and the veil of error vanished from before my eyes. She was not the famous actress at all, except in my wandering imagination. I then instantly recognized that her physical resemblance to the movie star was actually very slight. She was simply an artist’s model, a friend of one of the models I had used in my work. Her friend had pointed me out to her in the street, and had told her that I collected obscene photographs. She was referring to a collection of very fine photographic nudes that I had bought in Taormina, and that were pinned up on the walls of my studio. When she had met me in the museum of Etruscan jewels in Pope Julius’ villa it had occurred to her to offer to sell me her collection, and this was why she had pursued me, hoping to catch my eye and surreptitiously show me her forbidden wares.

This crude misapprehension that I had been led to worried me for several days, for it seemed to me to be the symptom of some mental disturbance. I had in fact experienced in the last few months a regular epidemic of more and more alarming errors and confusions. I felt myself to be overtaxed, and Gala took me off into the mountains, close to the Austrian frontier. We settled down in Tre Croci near Cortina, in a lonely hotel. Gala had to go to Paris for twelve days, and I remained there all alone.

Just at this time I received tragic news from Cadaques. The anarchists had shot about thirty people, all of them friends of mine, and among them three fishermen of Port Lligat to whom we were very close. Would I finally have to make up my mind to return to Spain, and share the fate of those who were close to me?

I remained constantly in my room, with a real terror of catching a cold and falling ill up there all alone, without Gala. Moreover, the landscape of high mountains has never pleased me, and I developed a growing resentment against the Alpine outdoors: too many summits around me! Perhaps I would have to return to Spain. In that case I must take care of myself! For if this should happen I would want to have the maximum of my life at my disposal for the sacrifice. I set myself to watching over my health with a maniacal rigor. When I noticed an ever so slightly abnormal mucosity in my respiratory regions I would rush for the electargol and put drops in my nose. I would gargle with disinfectants after every meal. I would become alarmed over the least sign of a skin irritation, and was constantly putting salves on almost imperceptible pimples which I feared would develop malignantly in the course of the night.

During my returning insomnia I would listen for the non-existent pains that I was expecting and for the diseases that must be about to pounce on me. I would feel around my appendix for the slightest sign of sensitiveness. I scrupulously examined my stools, which I would wait for with my heart in my throat. Actually my bowel movements were regular as clockwork.

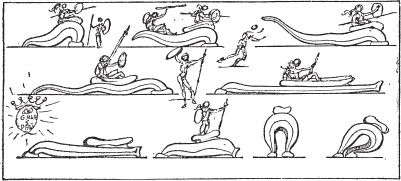

FROM HESSE, “TIERBAU UND TIERLEBEN” (TUEBNER)

DRAWINGS SHOWING THE MOVEMENTS OF A LEECH

For some five or six days I had noticed while I was in the very clean toilet a large piece of nasal mucus stuck to the white majolica wall close to where I sat. It was extremely repugnant to me, though I tried not to see it and to look elsewhere. But day after day the personality of this piece of mucus became more and more impossible to ignore. It was fastened to the white majolica with such exhibitionism, with such coyness, I might even say, that it was impossible not to see it and even not to look at it constantly. It seemed to be quite a clean piece of mucus, a very pretty, slightly greenish pearl gray, browner toward the centre.

This mucus ended in a rather sharp point, and stood out from the wall with a gesture that called stridently and with the trumpet-call of its insignificance for an act of intervention. It seemed to say to me, “All you have to do is to touch me, and I will let go and drop to the floor: that will put an end to your disgust.”

But, armed with patience, I would get up impatiently from the toilet without touching the mucus’s intact virginity, slamming the door in a fit of rancor and spite.

One day I could no longer stand it, and I decided to have done once and for all with the obsessing presence of this anonymous piece of mucus which with its loathsome presence was increasingly spoiling the satisfaction I derived from my personal stools. Screwing up my courage, I decided finally and irrevocably to wipe the mucus from the wall. In order to do this I wrapped up the forefinger of my right hand in toilet paper and, shutting my eyes and furiously biting my lower lip, with a gesture of savage violence into which I put the whole force of my soul exacerbated by disgust I tore the mucus from the wall.

But against my expectation this mucus was as hard as a tempered steel needle; and like a needle, it penetrated between the nail and the flesh of my forefinger, right to the bone! Almost immediately my hand became blood-soaked, and a violent, burning pain brought involuntary tears to my eyes. I went back to my room to disinfect my wounded finger with hydrogen peroxide, but the worst of it was that the lower and pointed part of the mucus had remained down inside my nail, so deep that I saw no way of getting it out. The sharp initial pain dwindled away, but soon it was replaced by that sub-sub-sub-rhythmic throbbing which I knew to be the perfidious and characteristic music of infection! Once the bleeding had stopped I went down into the dining room, pale as a ghost, and I explained the matter to the head waiter, who was always trying to engage me in conversation—which I habitually avoided by a dry and disagreeable tone of voice which admitted of no other response than silence. That day, on the other hand, my cowardice made me so human and communicative that he took advantage of it to pour himself out with all his stored-up effusiveness. He examined my finger closely.

“Don’t touch it!” I cried. “Look at it without touching it. What do you think? Is it serious?”

“It seems to have gone quite deep, but it all depends on what it is—a splinter, a needle, what is it?” I did not answer. I could not tell him the frightful truth. I could not tell him,

“That blackish thing which has pierced the forefinger of my right hand is a piece of snot!”

No, no one would have believed that. That kind of thing happens to no one but Dali. What was the use of explaining, when the reality was verily that of a purple-tinged hand that was clearly beginning to swell? The whole hand of the painter Salvador Dali, which it would be necessary to cut off, infected by a piece of mucus—if indeed it did not

devour me entirely, after first reducing me to nothingness amid the spasmodic and abominable convulsions of tetanus.

I went up into my room and lay down on the bed, ready for every martyrdom. I spent one of the blackest and most sinister hours of my life. None of the tortures of the civil war could be compared in intensity with the imaginative torment which I endured during that frightful early Alpine afternoon. I felt death weigh within my hand like two ignominious kilos of gesticulating worms. I imagined my hand already separated from my arm, a prey to the livid first symptoms of decomposition. What would they do with my cut-off hand? Would they bury it? Are there coffins, for a hand? It would be necessary to bury it, for it had already that “foul look” of corpses in an advanced stage of decomposition, looked at too often for the “last time,” so that even those who are most loving and closest to the deceased have no other thought but to hide it with horror—for it is no longer he! It begins to frighten! It threatens to begin to move! One can’t bear to look at it any longer! It is the imperialist unsepulchered cadaver which threatens one every moment with its tenacious swollen apparition, worse than anything one can imagine!

But even though it might be rotting, I did not want to separate myself from my hand! I could not resign myself to imagining it, when night had risen, far from me, finally shut up in the recipient in which struggled fetid gases corresponding to the progressive stages of decomposition of a corpse. I brought my hand to my mouth, and it was worse than if on the same spot someone had crushed the body of a monstrously heavy headless grasshopper!

I got up, maddened with moral suffering, drenched in the perspiration of death-agony, and I dashed to the toilet, where I got down on the floor on my knees to examine the rest of the mucus that ought to be still there. I did find it, and minutely examined it. No! It was not a piece of mucus! It was simply a drop of glue that must have fallen there, clinging to the majolica of the wall, at the time the painters had done over the ceiling of the toilet. The moment this was cleared up, my terror disappeared. I dug out the barb of hardened glue that had remained inside my fingernail with that strange attentive and voluptuous vertigo that had been masterfully immortalized in the famous piece of sculpture of the

Boy Extracting Thorn from His Foot

. Once I had removed the remnant of the “false mucus” from my finger, I immediately sank into a blissful heavy slumber.

When I awoke I knew that I should not leave for Spain.

I had already been there. And just as des Esseintes, the hero of Huysmans’

A Rebours

, had experienced the fatigue and the reality of his voyage to London before even beginning it, without moving from the station

bistrot

where he had imagined all the experiences of the travel and of his stay in London so powerfully that he could return home with the impression that he had made the whole journey,

just so I had just experienced a “civil war” in my own body, from which I had cut the very substantial piece of my own right hand.

Beings without imagination wearilessly undertake travels round the world; they will all need a whole European war in order to obtain a very vague idea of hell. All that I had needed, in order to descend into “hell,” was a piece of mucus, and furthermore a piece of mucus that was not even real—a piece of false mucus! Besides, Spain that knew me and that knows me knows it: were I to die, and no matter how I died, even if I should die of a piece of mucus or of false mucus, I should always die for her, for her glory. For unlike Attila under whose footsteps the grass no longer grew, each bit of earth on which I set my feet is a field of honor.

1

The whole pre-war and post-war period is characterized by the germination of “isms”: Cubism, Dadaism, Simultaneism, Purism, Vibrationism, Orpheism, Futurism, Surrealism, Communism, National-Socialism, among a thousand others. Each has had its leaders, its partisans, its heroes. Each claims the truth, but the sole “truth” which they have demonstrated is that once these “isms” are forgotten (and how quickly they are forgotten!) there remains among their anachronistic ruins only the reality of a few authentic individuals.

2

The cannon-shot of composition, old as the world—cubism

The cannon-shot of automatism—surrealism

The cannon-shot of ... etc., etc.

All “isms” were only cannon-shots, each one over a problem existing in any classic work. It is true that cannon-shots were the only means of making anything heard after the war, and all will have served for the classic works to come. For example, it is probable that in ornamental elements—reliefs, mouldings, acanthuses, friezes, and other architectual parts of a painting—a certain influence of surrealist automatism will be felt in future styles. But it would be naïve to pose the problem of style the other way round and derive a painting from a Louis XIV ornamental motif! A painting is a much more complete and complex phenomenon than the inspiration that one can put into drawing an acanthus leaf!

3

An elaborately decorated tent put up for dancing during village festivals.

4

“Spain is a granitic or calcareous plateau with

a

mean altitude of 700 metres.”

(Petit Larousse.)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Florence - Munich in Monte Carlo Bonwit Teller New European War Battle Between Mademoiselle Chanel and Monsieur Calvet Return to Spain - Lisbon Discovery of the Apparatus for Photographing Thought Cosmogony - Perennial Victory of the Acanthus Leaf Renaissance