The Secret of the Swamp King (6 page)

Read The Secret of the Swamp King Online

Authors: Jonathan Rogers

Bullbat Bay

Floyd ran to the stern to throw Aidan a rope, but it was no use. The current spun him away and the rope fell short. By the time Aidan managed to outswim the swirl, the raft was a hundred strides away, and the alligator hunters were having no success controlling it. Aidan eased himself into the current in the hope he could gain on the raft and be pulled in on a mooring rope. The raft, after all, couldn't go faster than the current. But in the alligator-infested Tam, Aidan preferred not to be in the water any longer than he had to, and he was very relieved when he saw the raft beach itself on a sandbar.

Aidan floated on his back until he got within a rope's length of the raft. Massey pulled him in the rest of the way. The alligator hunters were thankful Aidan was

unharmed, but they were also embarrassed that their foolishness had endangered him. They mumbled sheepish apologies, which Aidan readily accepted.

It wasn't the time to dwell on past mistakes. They had a big problem on their hands. It was hard enough to move a raft of timber when it was floating. But a raft of timber on the groundâthere was no budging it. Each log was fifteen strides in length, and most were so thick Aidan could barely reach around them at the base. It would take a mule to drag even one. Here they had forty such logs skidded halfway up their length onto the sandbar.

Floyd scratched his head. Now that Aidan was safe and sound, the magnitude of their problem was starting to dawn on him. “How in the world are we going to get this raft off this bar?”

It didn't take long for the three rafters to realize they would have to float the raft if they hoped to move it. “The river's been dropping for three days now,” observed Massey. “And if it keeps dropping, this raft'll be completely beached by tomorrow.”

“Spring rains is mostly over,” added Floyd. “River's headed back to its usual flow. Who knows when it might rise enough to float these logs.”

They all agreed that their best option was to take the raft apart, roll the logs one by one into the river, and refasten them on the water. With the river current, it was really more than a three-man job and could take days.

“We need a bigger crew,” observed Aidan. “But we're a long way from the nearest settlement.”

“Last Camp's another thirty leagues down the river,” Massey estimated, “and Longleaf's the nearest civilization in the other direction.”

“Some hunters might have an overnight camp nearby,” offered Floyd. “And the Overland Trail to Last Camp can't be more than a couple of leagues from the river. Maybe we can meet up with some hunters passing through who might help.” Any hunter who found himself in the Eastern Wilderness should be happy to help get the raft to Big Bend. The timber, after all, was for a stockade to protect anyone who used Last Camp.

Aidan, Floyd, and Massey pushed through the willow bank and into the scrub beyond. It was hard going as they picked their way among thickets of black haw bush and needle palm. The hoorah bushes were thick, too, with their tiny yellow flowers.

“Aidan, I bet you don't know how the hoorah bush got its name, do you?” said Floyd.

“No, I don't,” answered Aidan, “but I bet you're going to tell me.”

“Sure,” answered Floyd, holding a branch from a galberry bush so it wouldn't snap back and hit Aidan, “since you asked.”

“Long time ago,” began Floyd, “the sweat bees around here was just about to starve to death. Every time they went to get the nectar out of a flower, there'd be a big bumblebee's behind sticking out of it, crowding the sweat bees out of the action. And worse than that, the bumbles was bullyish about it. It wasn't no use for the little sweat bees to ask them nicely could they please have a

turn. The big bumbles just waggled their head feelers at them and kind of growled.

“For awhile there,” Floyd continued, “the sweat bees worked out a partnership with the lightning bugs. After the bumbles went to bed, the lightning bugs would light the way for the sweat bees to do their nectaring at night. They went halves on the honey.

“But that didn't last very long after the lightning bugs realized they didn't even like honey. Meantime, the sweat bees had got so grouchy from lack of sleep that they couldn't get along with their own selves, much less with the lightning bugs.

“Well, sir, the Lord looked down and had pity on the poor sweat bees. He caused a new bush to grow in the swamp. It had tiny little yellow flowers. Next morning when the bumbles went zooming off, they saw the new yellow flowers, and they thought they looked mighty toothsome. But the big bumblebees were too fat and broad to get at the nectar. They bumped and wiggled and growled and buzzed, but they couldn't get no more than their head feelers inside the little yellow flowers.

“But the little sweat bees, it was like they was made for the new flower and the flower for them. They'd march right into the front parlor and suck out the sweetest drop of nectar they ever tasted. The sweat bees were so happy to have a bush of their own, they made up a little song:

Hoorah, hoorah, hoorah,

Here's the bush for me.

Bumble grumble,

Roll and tumble,

You won't get a drop or crumble.

Hoorah, hoorah, hoorah,

Here's the bush for me.

“And ever since,” concluded Floyd, “that yellow-flowered bush has been called the hoorah bush.”

Aidan snapped off a sprig of hoorah bush and stuck it in Floyd's hair. “Hoorah, hoorah, hoorah!” he sang.

They were walking up a low sand hill now, and when they reached the top they could see a little more of the surrounding terrain. As Massey scanned the treetops, his face softened with relief and recognition; he was obviously getting his bearings. He pointed at a stand of tall cypresses that rose above the surrounding scrubby oaks. “There's Bullbat Bay,” he announced. “We can't be more than a half league from the trail.”

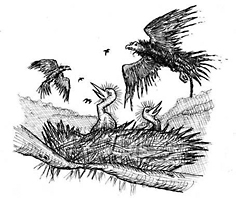

“That's Bullbat, all right,” Floyd agreed. “Look at them big nests.”

There were dozens of great stick nests in the treetops. Aidan could see it was a rookery for big birds of some sort. A buzzard came sailing into one of the treetops, then another. “Is it a buzzard rookery?” asked Aidan.

“No, not a buzzard rookery,” answered Massey. He shot a narrow-eyed look of concern at Floyd. “It's an egret rookery.”

When a trio of raucous crows came flapping and croaking from one of the nests, Massey and Floyd took off toward the bay. Aidan had to step quick to keep up with the hunters, who walked with long strides and

swinging arms as if drawn to the big cypress stand, even though they dreaded what they expected to find there.

Well before they reached Bullbat Bay, they were hit with a stench that lay over the place like a fog. The high whine of swarming bluebottle flies announced this was a place of death and corruption. When they got to the bay, they found the floor littered with the white carcasses of egrets. Dozens of the dead birds hung tangled in the bushes, lay contorted on the spongy ground, or floated where the water pooled. Their heads, backs, and breasts had been stripped of the long showy plumes that had been their glory. There was nothing glorious about this rookery now, where the magnificent white birds returned to the black muck.

Even more gruesome was the scene in the treetops. Squawking egret chicks sat helpless and unprotected in their stick nests. They stretched out their pink beaks, desperate for a meal that would never come. The crows and buzzards that lit on their nests came not to feed the chicks but to feed themselves. A single egret mother stood in a single nest, vigilantly guarding her young. But she had no mate to gather food for them or to take a turn protecting the nest so she could hunt herself. She faced a grim choice: to see her offspring starve or to leave them vulnerable to the carrion birds while she went in search of food for them.

“Plume hunters,” growled Floyd, and he spat on the ground in disgust.

Aidan stood in shock at such a scene of devastation. The sheer number of birds shot and left to rot was

nauseating in itself. But the timing of the slaughterâduring nesting season before the young egrets could fend for themselvesâensured that the colony would never recover. This rookery was gone for good.

Aidan could feel his eyes filling with tears. “Why nesting time?” he asked. Even a hunter who cared nothing for the Living God's creation should care enough about his own livelihood not to hunt his quarry to extinction.

“Nesting time's the only time a plume hunter shoots,” answered Massey. His face was red with anger. “It's the only time the birds wear their wedding plumage.”

“Every spring,” explained Floyd, “them poor birds put on their wedding plumes. They marry up, fix a little house out of sticks, have a few babies.” He smiled at the thought of the egrets' domestic happiness. “They're so proud and pretty.”

“That's when the plume hunters come,” said Massey. “Circle 'round a rookery like this one and shoot their crossbows into the treetops.”

“Big birds make easy targets,” Floyd added, “standing guard over their babies, as still as statues. And so brave and stupid, they won't fly away and leave their young'uns unprotected once the shooting starts.”

Massey picked up the grim account. “Before long, their mates sail in from fish hunting and light on the nest to feed their babies. Plume hunters shoot them too.”

What Aidan saw at Bullbat Bay was a sickening sign that things would never be the same in the Eastern Wilderness. And not just in the wilderness. He thought of

King Darrow and his paranoid rants and wondered if he would ever again be the king he had been as a young manâthe king who seemed to have reawakened three years ago when he led the charge that defeated the invading Pyrthens. He thought of his own father, so changed in the months since the king had discarded him. He thought of the fine ladies and gentlemen of Tambluff, in their fine plumed hats who either didn't care or kept themselves ignorant of the devastation wrought in the Eastern Wilderness so they could follow the latest fashions.

Aidan felt sick, as if his stomach had been turned inside out. He stood silent for a moment with his traveling partners. There was nothing they could do here; the irreparable damage had been done. And they were in desperate need of extra hands to help refloat the raft.

“There's a footpath on the far side of the bay,” said Massey at last. “It leads to the Overland Trail a quarter league from here.”

They walked the path without speaking.

Things are

changing in the wilderness,

thought Aidan. There were no written laws in the Eastern Wilderness. Or rather, there was no authority there to enforce any law. The nearest magistrate, in fact, was Aidan's father, all the way back at Longleaf. For the few people who ventured into the wilderness, the only law was a code of honor. No hunter took from the forest more than he neededâjust enough to eat, to clothe himself, a few extra pelts or hides to trade for the things he couldn't make or find. Nobody aimed to get rich from the forest. If that's what

people wanted, they would move to town or raise cattle or cotton. Settlers lived in the wilderness because they loved the wilderness, not because they wanted to tame it or to convert its resources into gold to line their buckskin pockets. The first law of the wilderness was to keep it wild.

Aidan was so lost in his own thoughts he paid no attention to the rhythmic squeaking he heard to the east. The forest, after all, was full of squeaks and chirps at all hours of the day and night. Floyd was the first to realize that these weren't the noises of frogs and birds. He stopped and cupped a hand to his ear. “Is that wagon wheels I hear?” Aidan and Massey stopped, too, and they heard the jangle of a mule harness. They ran the short distance to the trail. They couldn't see the wagon, but they could still hear it creaking northward toward civilization.

“Wait!” shouted Massey as they sprinted up the trail. They couldn't let these travelers get away; it might be days before anyone else came along this remote path. “Hold on!”

“Wait for us,” called Floyd.

The creaking of wagon wheels stopped. The wagoner had obviously heard them. When Aidan, Massey, and Floyd came running around the next bend in the trail, they skidded to a stop, shocked to find four sunburned men in buckskin breeches standing behind a wagon and aiming crossbows at them. Their eyes had the blank look of men who knew what it was to pull the trigger on another man. But the really mesmerizing thing about the

men was their enormous hair. It stood high on their heads and flipped back like great duck wings, plastered with potato starch on either side. It was the past year's fashionable hairstyle in Tambluff.

Aidan and his fellow travelers instinctively raised their arms and froze where they stood. The mule stamped at the sandy ground and jingled in his traces, and a rain frog

chirrripped

from a bush beside the trail, but there was no other sound in the tense moment.