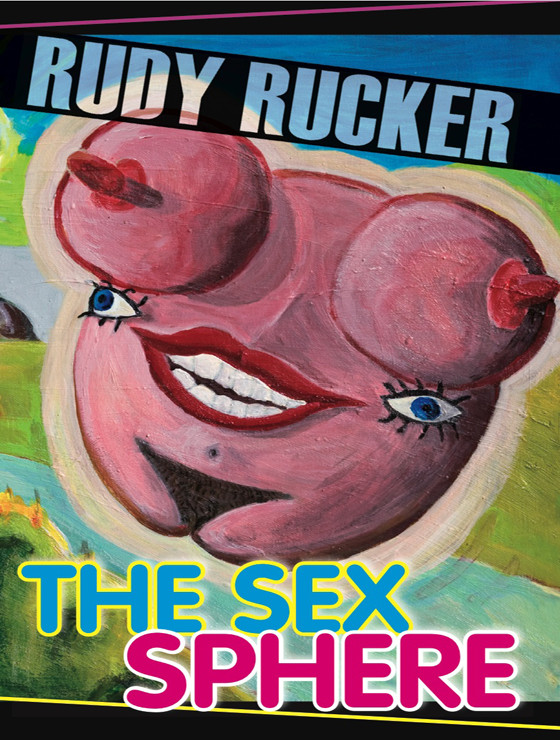

The Sex Sphere

Authors: Rudy Rucker

Tags: #Fiction, #Science Fiction, #General, #Adventure

THE SEX SPHERE

RUDY RUCKER

Copyright © 1983, 2008 by Rudy Rucker

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without permission in writing from the author.

All characters in this book are fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

First edition: Ace Books, October, 1983

Second edition: E-Reads, September, 2008

www.ereads.com

For Sylvia

“If we want to pass on and on till magnitude and dimensions disappear, is it not done for us already? That reality, where magnitudes and dimensions are not, is simple and about us. For passing thus on and on we lose ourselves, but find the clue again in the apprehension of the simplest acts of human goodness, in the most rudimentary recognition of another human soul wherein is neither magnitude nor dimension, and yet all is real.”

—Charles H. Hinton

“At first, indeed, I pretended that I was describing the imaginary experiences of a fictitious person; but my enthusiasm soon forced me to throw off all disguise, and finally, in a fervent peroration, I exhorted all my hearers to divest themselves of prejudice and to become believers in the Third Dimension. Need I say that I was at once arrested and taken before the Council?”

—Edwin A. Abbott

Introduction

This is a novel about higher dimensions, and about sexual love. I don’t need to explain much about the sex, which is, as always, a mixture of the erotic, the comic and the surreal.

But higher dimensions are less familiar. What I’d like to do in this introduction is to sketch some of the basic science ideas that I’ve used. Not that you have to read the introduction right now—you can check it out later, or never. It’s only here an extra. Proceed immediately to Chapter One, if you prefer.

Anyone left? Initiate professor mode...

The fourth dimension is a direction perpendicular to all the directions we can point to. Sometimes people say that time is the fourth dimension, and this is in some respects true. But to start with, we just want to get the idea of there being some unknown and higher possibilities of motion.

Figure 1: A Square

The best way to begin thinking about higher dimensions is to look at some two-dimensional creatures who have no notion of a

third

dimension. These creatures were invented by Edwin A. Abbott in his 1884 classic,

Flatland

. The best-known of the Flatlanders is one A Square (see Figure 1). By thinking about A Square’s difficulties in imagining a third dimension, we become better able to get over our own difficulties in understanding the fourth dimension.

Figure 2: A Square Looking at A Triangle and A Circle

The Flatlanders are confined to the surface of what seems to be an endless plane. They can move East/West, North/South, or any combination of these two directions. But it’s impossible for them to jump up out of their world and into the third dimension.

One minor point needs to be mentioned here. When A Square looks at two of his fellows, say A Triangle and A Circle, the Square’s actual retinal image is of two line segments—just what you would see if you were to lower your eye to the level of a tabletop on which some cardboard shapes were lying . But as the space of Flatland is permeated with a light mist, the edges of the triangle seem to shade off faster than do the edges of the circle. Thus our Square is able to distinguish his fellows’ shapes, and to form good mental images of them (see Figure 2). If you think about it, this is no more surprising than the fact that we’re able to use our two-dimensional retinal images to form three-dimensional mental images of the objects around us.

OK. Now how does A Square find out about the third dimension? A Sphere from higher-dimensional space takes an interest in A Square and decides to show herself to him. She does this by moving through the plane of Flatland. What does A Square see? A circle of varying size. And if we suppose that the sphere has a valley-like peach cleft, the cross-sectional circles will have little nicks (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: A Square Meets A Sphere

One of the main characters in

The Sex Sphere

is a hypersphere named Babs. When she moves through our space, our hero Alwin sees…what? A hypersphere is the higher-dimensional analogue of a sphere, so just as A Square sees a sphere as a

circle

of varying size, we can imagine that Alwin will see Babs as a

sphere

of varying size.

We can imagine that A Sphere would be able to lift A Square out of his space, and it’s equally possible to suppose that Babs might lift Alwin out of our space. Alwin could either tumble about in this higher space, or he might “slide” on the surface of Babs herself, just as A Square could be thought of as sliding up along Sphere’s swelling flank.

It’s interesting to realize that hyperspheres are not utterly fictional concepts. As early as 1920, Albert Einstein suggested that the three-dimensional space of our universe is curved back on itself to form a great hypersphere. The important thing about a hyperspherical space is that it is finitely large, yet one never comes to an edge of it. This is, of course, analogous to the fact that our Earth’s spherical surface is finite and without edges.

Figure 4: A Knot in Sphere’s Tail

Suppose that A Square became so interested in A Sphere that he wanted to prevent her from leaving his space. What could he do? If we think of the Flatland space as being a sort of soap-film, then there might be some possibility of stretching out a long piece of our space, pulling out a long piece of Sphere, and tying the two together with a square knot (see Figure 4)! A physicist named Lafcadio Caron does something analogous to this in our book. He manages to knot the tail of Babs-the-Hypersphere into our space. Babs doesn’t like this. Much of the book’s action is in fact directed by Babs—her goal is to get some people to carry out a certain act which will free her tail from the knot.

Towards the end of the book it develops that Babs is more than just a four-dimensional hypersphere. She is really a pattern in infinite-dimensional “Hilbert” space. Why would I want to drag in so many dimensions?

Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity has taught us to think of gravitational force as being a result of the

bending of space

. That’s one higher dimension, at least. Yet Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity tells us that the basic reality is not space, but

spacetime

. So here’s another higher dimension. Three space dimensions, one time dimension, one dimension to curve spacetime in—that’s five already. But any lover of SF knows that there are many parallel curved spacetimes—alternate universes—so we’re going to need a sixth dimension to stack these spacetimes in.

Before going on to Hilbert Space, let’s just stop a minute and think about how neat spacetime is. If we take “up” to be the same as “future,” then the spacetime of Flatland will be a sort of block, a stack of “nows.” An elementary particle can be thought of as tracing out a line in spacetime, a world-line something like the afterimage of a sparkler’s trail. Insofar as I am made up of elementary particles, I am a sort of

braid

in spacetime, a macramé pattern in the universal tapestry (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: People are Spacetime Braids of Particle Worldlines

What’s particularly interesting here is to realize that the process of breathing particles in and out serves to weave us together; and—which is more important for the story—the concept of “family tree” has a real significance in spacetime. Not to give too much away, when our character Alwin starts tumbling off into the direction of the “future,” he drags his children after him. Note that if someone were able to pull their past selves out of spacetime, then no one would even remember them!

In modern physics, the fundamental reality is thought of as infinite-dimensional. This fact is not widely known—people just don’t know what to make of it. What you have to do to appreciate the world’s infinite-dimensionality is to realize that our ordinary concepts of space and time are just

constructs

. What is in fact immediately given to us is an unstructured sea of thoughts and perceptions. We try to impose order by using a four-dimensional spacetime framework.