The Sexual History of London (31 page)

Read The Sexual History of London Online

Authors: Catharine Arnold

Ashbee's stated intention was to illustrate how widespread pornography actually was, and what a vast field of human and aesthetic experience it covered, and to preserve it for future generations. After all, Ashbee remarked,

most of the books of this class are printed either privately or surreptitiously, in small issues, for special classes of readers or collectorsâ¦they do not usually find their way into public librariesâ¦but are for the most part possessed by amateurs, at whose death they are not unfrequently burned; and they are always liable to destruction at the hands of the lawâ¦their scarcity is very much in proportion to their age; and as society is constantly at war with them, the natural course is for them to die out altogether.

40

Ashbee's cataloguing technique was systematic bordering on obsessive. Unlike other bibliophiles, he made it his rule ânever to criticise a work which I have not read, nor to describe a volume or an edition which I have not examined'

41

and was scrupulously methodical: âIn treating of obscene books, it is self evident that obscenities cannot be avoided. Nevertheless, although I do not hesitate to call things by their right names, and to employ technical terms when necessary, yet in my own text I never use an impure word when one less distasteful but equally expressive can be found.'

42

Ostensibly, Ashbee's attitude towards pornography was objective, and detached. Writing as though he had no personal interest in the acts depicted, but was describing the effects of toxic chemicals, Ashbee warned readers that these books âshould be used with caution even by the mature; they should be looked upon as poisons, and treated as such; should be distinctly labelled, and only confided to those who understand their potency, and are capable of rightly using them'.

43

Most important of all, the books should be kept out of the hands of the young and the impressionable. Ashbee even made a somewhat spurious claim that pornography possessed a moral purpose, and that âimmoral and amatory fiction' deserved study on the grounds that it contained âa reflection of the manners and vices of the times, vices to be avoided, guarded against, reformed', which sounds like a typical example of Victorian hypocrisy when Ashbee's life and activities are considered in more detail.

One glaring omission was

My Secret Life

by âWalter', published in Amsterdam around 1890, and therefore appearing too late to be included in the catalogue. It consists of eleven crown octavo volumes (a total of 4200 pages), rather poorly printed on handmade ribbed paper.

44

Errors in typography, spelling and grammar suggest that it was set by a French compositor, while the identity of the author is kept secret by the omission of names, locations and dates. Although each title page bears the imprint âAmsterdam. Not for publication', the work was clearly designed to be circulated to a select number of readers; subsequent owners of the books included Aleister Crowley, Josef von Sternberg, Lord Mountbatten and Harold Lloyd.

My Secret Life

consists of the sexual memoirs of a Victorian gentleman, recorded over a period of forty years. It is the distillation of a lifetime of dissipation during which he has probably âfucked something like twelve hundred women, and have felt the cunts of certainly three hundred others of whom I have seen a hundred and fifty naked'. During the period he has had âwomen of twenty-seven different Empires, Kingdoms or Countries, and eight or more different nationalities, including everyone in Europe except a Laplander'.

45

If not exactly well written, the book is an unflinching account of his sexual exploits, mostly with prostitutes. While âWalter' does not emerge as an attractive man, his honesty and authenticity are refreshing, as are the occasional bouts of self-disgust, although his somewhat brutal approach is unlikely to appeal to female readers, as in the following example. After a three-way encounter with a prostitute and a drunken sailor, during which âWalter' pays the couple to have sex while he watches (and then joins in), âWalter' staggers home to find his wife is still awake: âOn entering my room there sat she reading, which was a very unusual thing. I sat down wishing she would leave the room, for I wanted to wash; and wondered what she would say if she saw me washing my prick at that time of night, or heard me splashingâ¦'

After going for a wash, and being kept awake by âfear of the pox', âWalter' finds the memory of the previous escapade so exciting that âmy prick stood like steel. I could not dismiss it from my mind. I was so violently in rut. I thought of frigging, but an irrepressible desire for cunt, cunt and nothing but it made me forget my fear, my dislike to my wife, our quarrel, and everything else â and jumping out of bed I went into her room.

âI shan't let you, â what do you wake me for, and come to me in such a hurry after you have not been near me for a couple of months, â I shan't, â I dare say you know where to go.'

But I jumped into bed, and forcing her on her back, drove my prick up her. It must have been stiff, and I violent, for she cried out that I hurt her. âDon't do it so hard, â what are you about!' But I felt that I could murder her with my prick, and drove, and drove, and spent up her cursing. While I fucked her I hated her, â she was my spunk-emptier. âGet off, you've done it, â and your language is most revolting.' Off I went to my bedroom for the night.

46

And even this is not enough to keep âWalter's' mind off the sailor.

After I had got over my fears I had a very peculiar feeling about the evening's amusement. There was a certain amount of disgust, yet a baudy [

sic

] titillation came shooting up my bullocks [

sic

] when I thought of his prick. I should have liked to have felt it longer, to have seen him fuck, to have frigged him till he spent. Then I felt annoyed with myself, and wondered at my thinking of that when I could not bear to be close to a man any-where, I who was drunk with the physical beauty of women. The affair gradually faded from my mind, but a few years after it revived. My imagination in such matters was then becoming more powerful, and giving me desire for variety in pleasures with the sex, and in a degree, with the sexes.

47

âWalter' turns a cold, appraising gaze on Victorian sexual activities, and has an eye and an ear well tuned to the nuances of London low life which makes him an invaluable social commentator. Every detail of every sexual escapade is clear, âthe clothes they wore, the houses and rooms in which I had themâ¦the way the bed and the furniture were placed, the side of the room that the windows were on, I remember perfectly'.

48

And there is also a marked emphasis on the commercial transaction of paying for sex; on one occasion, he is rendered almost impotent by the fact that he cannot reciprocate a young woman's advances after Derby Day because he has gambled away all his money at the races. Despite the girl's response: âNever mind! Do me!' âWalter' is almost unmanned until he finds a spare half a crown. The girl pockets the money and moments later, âwe stroked ourselves into Elysium'.

49

Not for nothing was âspending' his favourite term for ejaculation. âWalter' was the ultimate Victorian punter, obsessed with âcunt', and shows some grudging respect towards prostitutes but a rapacious attitude towards servants and young girls: as far as he was concerned, every woman had her price. The effect of reading âWalter' for any length of time is one of monotony, as it is in the case of reading any obsessive author: the reader is almost bludgeoned into insensitivity, no matter how potentially arousing the subject matter, by the blunt instrument of the Anglo-Saxon sexual terms. Erotic prose is an art at which few English writers excel, as evidenced by the Pyrrhic victory of the âbad sex awards' presented to British novelists in the late twentieth century. As Ashbee commented on another title, while comparing English erotic authors unfavourably with their French counterparts, âthe copulations which occur at every page are of the most tedious sameness; the details are frequently crapulous and disgusting, seldom voluptuousâ¦gross, material, dull and monotonous'.

50

So keen was âWalter' to conceal autobiographical details that little is known of the author's public life, although his memoir offers some clues. Like Henry Spencer Ashbee, âWalter' was born in London to a prosperous middle-class father and went into business. He inherited a small fortune on the death of his father, and, when the money ran out, married a rich woman whom he despised, and he evidently had some success in business. Ashbee founded and became senior partner in a firm of London merchants called Charles Lavy & Co., and married his partner's daughter, Miss Lavy, a wealthy Jewish woman, while âWalter' also married a Jewess, his boss's daughter. It was not a happy union, although it did provide enough money to spend on prostitutes. âWalter's' wife died when he was thirty-five, much to his delight: âHurrah, I was free at last!'

51

â

Walter' then met Helen Marwood, a woman with whom he âdid, said, saw and heard, well nigh everything a man and a woman could do with their genitals',

52

and who inspired him to keep writing the sex diary which he had begun in his twenties.

The parallels between the life and interests of Henry Spencer Ashbee and âWalter' have been commented upon and more than one authority has suggested that âWalter' may have been Ashbee. Although both writers demonstrate a certain obsessive-compulsive attitude towards matters of a sexual nature, the theory does beg one question: if Ashbee was âWalter' then why, as a self-professed connoisseur of pornography, would he have taken refuge in a pseudonym? Was he, like Pepys, writing primarily for his own pleasure, so that he could dwell on his conquests in his old age? Did

My Secret Life

perform the function Oscar Wilde required of a diary, in that it was âsomething sensational to read on the train'? âWalter' found himself one sympathetic reader in the form of Helen Marwood, who enjoyed telling him about her âformer tricks' in return for hearing about his own âamatory career'. âShe had read a large part of the manuscript, or I had read it to her whilst in bed and she laid quietly feeling my prick. Sometimes she'd read and I listen, kissing and smelling her lovely alabaster breasts, feeling her cunt, till the spirit moved us both to incorporate our bodies.'

53

It is a curiously domestic, even cosy, conclusion for a man whose preferred sexual encounters took place for money, with strangers, down dark alleyways.

While âWalter' took a certain degree of homosexual play in his stride, never questioning his essentially heterosexual nature, the lives of genuine homosexual men continued to be overshadowed by prosecution and even death, as becomes evident in the following chapter.

âDoes it really matter what these affectionate people do â so long as they don't do it in the streets and frighten the horses?'

Mrs Patrick Campbell

In 1833, William Bankes, MP for Dorset, was discovered âstanding behind the screen of a place for making water against Westminster Abbey walls, in company with a soldier named Flower, and of having been surprised with his breeches and braces unbuttoned at ten at night, his companion's dress being in similar disorder'.

1

Bankes was lucky to escape a jail sentence. Aristocrats, professors and clergymen testified to the effect that âhe was never yet known to be guilty of any expression bordering on licentiousness or profaneness and the jury acquitted him despite incriminating evidence on the grounds that his character was not that associated with sodomites'.

2

This appears to be a clear example of how far the establishment would go to protect an open secret, and Bankes's reputation seemed safe. Unfortunately for him, however, in 1841 he was caught in a compromising position with a guardsman in Green Park, and fled the country before he could go on trial for a second time. Under the Buggery Statute of 1533, initiated by Henry VIII, homosexual activity was technically punishable with death, although conviction was difficult, as the witness had to have seen penetration.

3

Leaving scandal in his wake, Bankes died abroad in 1855. Like many homosexuals of this era, he was condemned to end his days in exile.

There have been many words for homosexuality and gay sex, but the actual term âhomosexual' originates with a Hungarian physician named Benkert in 1869.

4

Of course the expression covers an entire range of sexual behaviour, but, for the duration of this chapter, âhomosexual' best serves to describe the personalities and activities depicted. In some respects, the homosexual underworld operated like a parallel universe. Just as the top-drawer whores went unacknowledged and unmolested by the police, so a blind eye was often turned to homosexuality in high places if the protagonists were sufficiently well connected, and cover-ups to protect the reputation of the culprits were not unknown. If William Bankes MP had been a little more discreet, perhaps he would not have been forced to flee abroad and leave his beloved stately home, Kingston Lacey in Dorset, and his considerable collection of Egyptian antiquities.

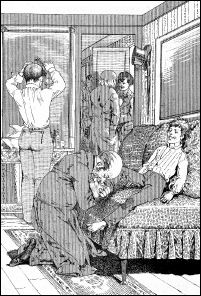

A nineteenth-century male brothel, from a French study of prostitution, where boys from the street are made available to clients. Here one man is passionately kissing a boy's foot (1884).

Other politicians sailed close to the wind without falling foul of the legal system. For instance, George Canning, briefly Prime Minister back in 1827, was said to make advances to any pretty young man around the House of Commons, while future Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli was, if not actually homosexual, then outrageously camp, noting in his novel

Coningsby

that âat school friendship is a passion. It entrances the being; it tears the soul.'

5

Disraeli's reference to âschool' is significant here. Institutionalized homosexuality had long been a feature of the English public-school system. Commenting on the fate of Oscar Wilde, the editor William Stead noted: âShould everyone found guilty of Oscar Wilde's crime be imprisoned, there would be a very surprising emigration from Eton, Harrow, Rugby and Winchester to the jails of Pentonville and Holloway. Until then, boys are free to pick up tendencies and habits in public schools for which they may be sentenced to hard labour later on.'

6

Despite the best efforts of individual headmasters to stamp it out, homosexuality was a recurrent element of public-school life.

The classical traditions which formed the basis of the educational curriculum extolled the virtues of love between young men â or a young man and an older one â as the ideal, in keeping with the original text of Plato's

Phaedrus

. The Old Testament also supplied an example, in the relationship between David and Jonathan, which was considered âwonderful, passing the love of women'.

7

On a more earthy level, the system lent itself to abuse, with its âfagging' (not a reference to homosexuality but the tradition by which younger boys became the slaves of older pupils), flogging, âbeating, buggery and boredom' as Ronald Pearsall so eloquently expresses it.

8

At Harrow, for instance, pretty boys were given girls' names, such as âNancy', and became the âbitches' of older boys. Very few boys had the strength of character, or the desire, to withstand the combination of social pressure and temptation, although William Gladstone, stalwart as ever, insisted that he did not succumb during his time at Eton. According to his biographer, he âdid not stand aside from the harmless gaiety of boyish life, but he rigidly refused any part in boyish indecorums'. The harmless gaiety, for the record, consisted of playing chess and cards in the evenings, and taking a boat out on the river without authorization.

9

While relationships between pupils were commonplace, affairs between pupils and teachers were not unknown. Dr Charles Vaughan, appointed headmaster of Harrow in 1844 in his late twenties, noticed early on that the boys were passing compromising notes to one another, and attempted to put an end to these activities by forbidding the use of feminine names and threatening his charges with flogging. But Vaughan himself was tempted: in 1858, he became involved with a boy named Alfred Proctor. Proctor confided in another boy, John Addington Symonds, telling him he was having an affair with the headmaster. Although homosexual himself, Symonds was so shocked that he eventually revealed this information to his tutor at Oxford, and Vaughan had to resign.

10

Oscar Browning (1837â1923) experienced violent crushes at Eton. âWhy I should love Prothero as I do I cannot tell, but I do love him and I believe that that love ennobles me and purifies me,' he confided to his diary;

11

and, a year later, he was in love with âDunmore', entranced by everything about him, from his eyes and his manner to the fact that he was a lord.

12

Browning went on to become a master at Eton, where he became helplessly attracted to the young George Nathaniel Curzon, to such an extent that his âirrepressible attentions' caused hilarity among the boys. As Pearsall tells us, â“spooning” [caressing and kissing] between master and boy was a subject for cruel jest, but it was also accepted as part of the order of things'.

13

Obvious homosexual tendencies did little to harm Browning's reputation. He went on to become a fellow and tutor at King's College, Cambridge, and a member of the Apostles, the exclusive Cambridge debating society. Browning had found his niche. At Cambridge, he was fortunate enough to inhabit a realm in which institutionalized homosexuality flourished. Dons at Oxford and Cambridge were free to indulge their eccentricities. These ancient seats of learning were exclusively male (Girton, the first residential college for women, did not open until 1869) and the majority of dons were bachelors, as they were deprived of their fellowships if they married. The only women to penetrate the hallowed portals were bedders (chambermaids) and cooks. For intelligent, worldly, upper-class men, college life was a homosexual haven, a continuation of public school and an entrée to the establishment: the only requirement being that one must be reasonably discreet.

The homosexual scene in London was rather different. Instead of the Platonic ideal of master and boy, which flourished at Oxford and Cambridge, London had a ready supply of ârenters', or rent boys, and an avid clientele of men ready to take advantage of them. As the author of

The Yokel's Preceptor

described the situation in 1855, âthese monsters actually walk the streets the same as the whores, looking for a chance'. Fleet Street, Holborn and the Strand were favourite cruising grounds, and, according to the

Preceptor

, signs in the pubs around Charing Cross warned drinkers to âBeware of Sods'. The

Preceptor

was, of course, written as a guidebook for out-of-town homosexuals, and contained useful tips such as the observation that if you were actually going in search of a âsod', the favoured signal consisted of âplacing their fingers in a peculiar manner underneath the tails of their coats' and waggling them about, which was apparently âtheir method of giving their office'.

In addition to being referred to as âsods' (short for âSodomite'), homosexuals were also known in vulgar slang as âmargeries' and âpoofs', while any homosexual act was referred to as âbackgammon', which must have proved confusing for those pub-goers who anticipated nothing more exciting than a board game. There were homosexual brothels, such as the one next to Albany Street barracks run by a Mrs Truman, and there were clubs, such as The Hundred Guineas, where, in the tradition of molly houses, the members were given girls' names. For the most part, this twilight world flourished discreetly, but being a homosexual in London had its dangers, as the example of William Bankes MP has already illustrated. The stakes were higher: the illegality of the act made every homosexual a target for blackmail, either by his renter or a third party. Exposure meant public humiliation, family shame, exile or jail. As though predicting his own downfall, Oscar Wilde likened hanging out with his renters to âfeasting with panthers'. And of course it was Wilde who was engulfed in the greatest scandal of all.

But before I turn to the trials of Oscar Wilde, let us consider three other cases which cast a bright and unwelcome spotlight on London's homosexual underworld.

In April 1870, three men appeared in the dock of Bow Street Magistrates' Court, charged with attending the Strand Theatre with intent to commit a felony. There was nothing unusual about such an event, although the addresses given by the accused were from the smart end of town: one of them lived in Berkeley Square, Mayfair; another resided at Buckingham Palace Road. What did make this scene unusual was the way two of these men were dressed.

Ernest Boulton, twenty-two, wore a cherry-coloured silk evening dress trimmed with white lace; his arms were bare, and he had on bracelets. He wore a wig and plaited chignon. The costume of Frederick William Park, twenty-three, consisted of a dark green satin dress, low-necked and trimmed with black lace, of which material he also had a shawl round his shoulders. His hair was flaxen and in curls. He had on a pair of white kid gloves. The third gentleman, Alexander Mundell, also twenty-three, was more conventionally attired.

Superintendent Thomson, of E Division, was called by the prosecution and stated that at half past ten o'clock on Thursday evening, he went to the Strand Theatre and saw the prisoners in a private box, Boulton and Park being in female costume. He noticed their conduct and saw one of them repeatedly smile and nod to gentlemen in the stalls. As they left the theatre the prisoners were arrested and taken to Bow Street police station. Thomson's colleague Sergeant Kerley added that on their way to the station, Boulton and Park begged him to let them go and offered a bribe if he would listen to them, any sum he required. Boulton and Park were defended by a Mr Abrams who argued that the charge of felony was without foundation, and that the prisoners were guilty of nothing more than âhaving a bit of a lark'. For the prosecution, Mr Flowers retorted that they had indulged in this so-called âlark' for a very long time, and that he suspected the prisoners had a more serious purpose, such as enticing gentlemen to their apartments to extort money from them. Mr Abrams denied this suggestion.

14

The court case which followed demonstrated that this âlark' had indeed been of a long duration, and the story itself was so bizarre that it attracted considerable attention. In May 1871, a year after their first appearance at Bow Street Magistrates' Court, Boulton and Park made their debut in the High Court charged with âconspiring and inciting persons to commit an unnatural offence'. It was a big case, with the attorney-general and the solicitor-general appearing for the prosecution. The attorney-general started by saying that it was an unpleasant duty to have to conduct such a prosecution against such well-educated young gentlemen, but that he had no alternative.

15

So who were these two well-educated young gentlemen, and how on earth did they end up in court?

Ernest Boulton came from a respectable background and was employed by his uncle, a stockbroker. He was an attractive young man with a good singing voice, described as a soprano. Frederick William Park, meanwhile, was articled to a solicitor. In their spare time, the young men enjoyed amateur dramatics, and their favourite activity was dressing up as women. This again seems to have been regarded as a relatively blameless pastime. The trouble was that these âlarks' began to dominate their everyday lives, and they started hanging around in music halls such as the Alhambra, in Leicester Square, and in the Surrey Theatre, south of the river. John Reeves, manager of the Alhambra, told the court that they had been summarily ejected for causing a disturbance by being dressed up as women and trying to pick up men.

16