The Shapeshifters (60 page)

Authors: Stefan Spjut

There was a bit of a rush in the shop after that. There always is after a presentation, that's why we have them. Susso and I were at the counter and Roland helped too, although mostly by yapping with the customers. Torbjörn was also there, standing with Susso's backpack over one shoulder. He was a little pale and I asked him how he was feeling, but all he did was look at me.

Edit Mickelsson and her son Per-Erik had watched the presentation, looking deadly serious in their seats at the end of the front row, but Carina and Mattias had not been with them. They all came to the shop, though. Edit was wearing a small fur hat and came up to the counter to shake hands, but the others stayed

by the shop door, content to say hello from a distance. Susso crouched down to look into the boy's eyes. She held out her hand and tugged gently at his jacket as she spoke to him. He smiled and nodded, with the tip of his little nose tucked into his collar. Before they left, Mattias's mother gave Susso a tight hug and I noticed tears in her eyes.

As it started to empty out at around four-thirty Susso and Torbjörn went home, and I was just about to switch off the till when a girl came into the shop pushing an elderly woman in a wheelchair. I had noticed them before the slideshow because they stood out from everyone else. The lady in the wheelchair had large dark glasses like a film star and was wearing a fur-trimmed poncho in an expensive-looking fabric. Cashmere, I thought. The girl pushing the wheelchair was about fifteen and looked foreign. Her hair was short and raven black and she said nothing.

I said hello and the woman in the wheelchair replied, asking very graciously if we were about to close. Not at all, I assured her. She thanked me for the presentation, praised Dad's outstanding photographs, especially the ones from Lofoten, where she came from. She asked if I was his child, and when I nodded she asked if I was his only child. No, I said, I also have a sister. And I told her how we had moved with Mum from Riksgränsen to Kiruna when we were children and that Dad had stayed up there on his own.

âYou must have longed for him very much,' the woman said.

âDreadfully.'

âIsn't it remarkable how very strong our love for our parents is, despite all their faults?'

I agreed. It was an infinite love. Unconditional.

âAs a child you are prepared to do

anything

for them.'

âYes,' I said. âAnything at all.'

âYou forgive them everything.'

âEverything.'

The woman sighed and turned her face to the ceiling. The spotlights were reflected in her glasses. It looked like she had white pupils in a pair of black eyes.

âThat must be the worst thing that could happen to a child,' she said. âLosing its mother or father.'

âNo child should have to go through that,' I said.

âJust as no parent should have to lose a child.'

âNo, that's awful,' I said. âI've come close to that, so I know.'

âWhich is why we have to look

after

them,' she said, looking at me. âMake sure they don't come to any harm. We have to

watch over

them. Like a

binne

, a she-bear!'

âYes, of course,' I said. âIt is our responsibility. Our duty.'

âOur duty,' she repeated, nodding in agreement.

Then she pulled off her glove and extended her right hand, which was thin and a little crooked, so I held it gently. As I shook it she looked at me and said once again: âOur duty.'

Then she withdrew her hand, remarkably slowly.

That was when I felt the claw, lightly scratching my palm, and when I looked down I saw that two of her fingers were hairy and deformed.

Slowly she pulled on her glove, nodded at me and smiled, and then the girl wheeled her out of the shop. I stood there speechless, with my hand still outstretched. Roland pushed his glasses onto his forehead and asked what was wrong.

âDidn't you see?' I said. âDidn't you see her hand?'

He had not seen it. So I described how her little finger and index finger were covered in tufts of fur, how instead of nails she had claws!

He didn't believe me, I could see that. But we had spent a long time talking about what had happened and how the troll on Färingsö had turned into a bear, and Roland had even met the squirrel, which Susso had agreed to extremely unwillingly, so he dared not say anything.

I slumped down on the stool at the end of the counter. I could still feel the touch of her soft fur and hard claw in my hand. It felt as if she had taken my hand away from me. Or as if it was no longer my hand.

âBut that was definitely a threat,' he said. âShe threatened Susso. In that case we've got to phone the police. It was a death threat. I'm a witness.'

âBut don't you understand, Roland? They're the same creatures John Bauer was dealing with. The stallo. They're not human. The police can't do a thing.'

âThat was an eccentric woman, I'll give you that, but no way is she a troll. The police

can

arrest her. For threatening behaviour. That's a prison offence.'

âIt wasn't even a threat . . .'

âIt was a veiled threat, no doubt about it.'

I was shaken and tired so we said no more. We got a Thai takeaway and walked home in silence. Was it going to begin again, I wondered? And here was me thinking it was all over. On the way up I rang Susso's bell. I had to press the button several times and even knock before she shouted for me to come in. The venetian blinds were closed and the TV was on. She was sitting on her bed in her knickers and a T-shirt. Her hair was unwashed and she was wearing her glasses. I looked at her briefly before my eyes were led to the ceiling. I knew where the squirrel usually sat, and just as I thought, there it was on the curtain rail, looking down at

me watchfully. Despite everything it had done for us I had really started to dislike it, but that was not something I could say out loud or even really

think

about in its presence, so I tried looking in another direction.

When I told her about the woman who had come into the shop all she did was nod.

âTrolls can have children with humans,' she said. âBut then the children turn out like that. Deformed. So it's not surprising they take fully human children instead.'

âHow do you know that?'

âSkrotta told me.'

âWho?' I asked.

âSkrotta.'

âWho, him?' I said, nodding in the direction of the squirrel. âIsn't his name Humpe?'

âHe's called Skrotta. That's what he said.'

âHe

said something?'

Susso shook her head. âHe didn't need to.'

She thought everything would be all right now that she had taken down her website. So I had no need to worry. She got up and walked towards the door, more or less pushing me out.

But what about the bear? Had she forgotten that she had shot one of them? It was in self-defence, she said. She was sure he understood that. If she left the trolls alone now, they would leave her alone too. It was as easy as that.

She guided me out to the stairwell, where Roland was waiting patiently with our takeaway.

âHas the squirrel told you that as well? That they're going to leave you alone now?'

But she didn't answer. She just closed the door.

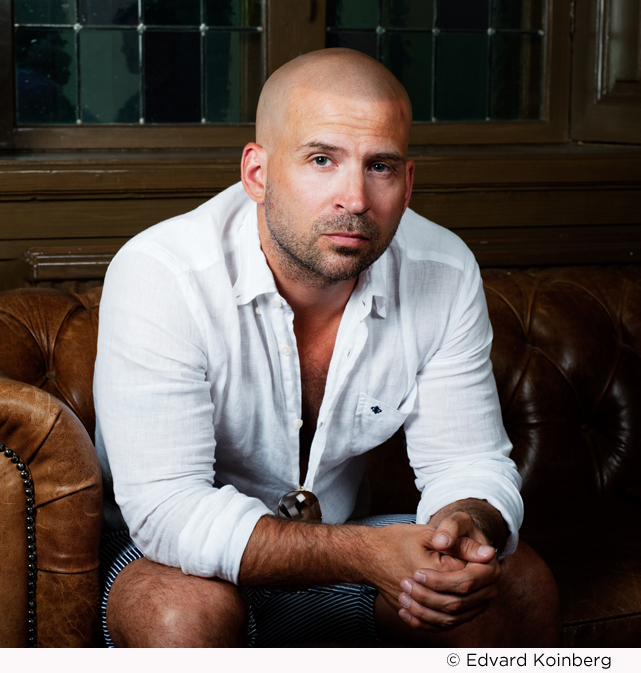

S

TEFAN

S

PJUT

was raised on the rural islands of Mälaren. He served with the Lapland Ranger Regiment and studied art, literature, philosophy, and journalism at Stockholm University. He lives in Stockholm with his two children.