The Shell House (13 page)

Alex and I are the ones who’ll lose, Edmund thought. Either way.

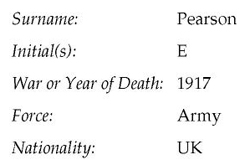

Website

Image

downloaded from

the

Commonwealth

War

Graves

website:

a slab of smooth, greyish-white stone, the base of a war memorial. In close-up, we read in carved lettering: THEIR NAME

LIVETH FOR EVERMORE. At the base of the

slab are propped two circular wreaths studded

with artificial poppies. A handwritten label is

attached to each wreath.

Late on Tuesday evening, when everyone else had gone to bed, Greg sat at the computer, dialling up the internet connection.

A simple search took him to the Commonwealth War Graves website. The home page showed a list of contents, and a caption

Their Name Liveth for Evermore

. At the bottom,

To search the register click here

.

The click took him to a picture of a memorial slab, and

This Register provides personal and service details of

commemoration for the 1.7 million of the Commonwealth

forces who died in the First or Second World Wars

. This was more comprehensive than Greg had hoped for. If Edmund Pearson had died in the army, he would be here. A few clicks of the mouse could reveal what had happened to him, and where. Greg’s senses quickened with a hunter’s excitement as he followed the instructions to

search the register

.

The search brought up a list of ten E. Pearsons, each with his rank, regiment and date of death. Greg scanned them eagerly. Not one of them was from the Epping Foresters, and only one was an officer, Second Lieutenant E. J. Pearson. Another click identified him as Edward John Pearson of Northampton, a second lieutenant in the Royal Field Artillery, who had died on 2 August 1917 aged twenty-five and was buried in the Huts Cemetery at Ypres in Belgium.

Greg checked the other nine just in case, then tried 1918, but found nothing that could possibly be Edmund Pearson of Graveney Hall. A blank. Edmund had slipped away again.

He stared at the screen in frustration. Now what? On an impulse he typed in his own name. G. Hobbs, Army, First World War yielded twenty-six names. There would be twenty-six gravestones with his name on them. Thinking of the fictional selves he had invented for himself, Jordan and Gizzard, he tried the other two names. Of J. McAuliffes there were eight, of G. Guisboroughs none, which seemed to confirm his view of Gizzard as a natural survivor. He wondered about the real men who had worn his name and Jordan’s into battle and into death. But not, it seemed, accompanied by Edmund Pearson.

He called Faith on her mobile.

‘What?’ Her voice was thick and blurry. ‘I’m in bed!’

In his urgency to tell her, he’d forgotten how late it was. He explained about the website, then: ‘He’s not listed, Edmund I mean, not in all the 1.7 million! That means he

can’t

have died in the war.’

‘What, then? We know he’s not in the graveyard with his relations. We know he’s not in a Commonwealth War Grave. So where is he?’

‘And why didn’t he come back to Graveney Hall?’

‘I know!’ Faith said, sounding properly awake. ‘I’ll ask Dad to help me check the

Births, Marriages and

Deaths

in the church records. Even if he didn’t live at Graveney he’d be in there if he got married or had children, and when he died. If he came back to the area at all.’

‘What if—?’ Greg was thinking aloud.

‘What if what?’

‘What if he was a deserter?’

There was a pause while they both thought about this. Then Faith said, ‘They shot them, didn’t they?’

‘If they were caught. What if he got away with it?’

‘But why should you think he was a deserter?’

‘Because I can’t think of anything else that makes sense,’ Greg said.

At the pool early next morning, perched on his high seat, he watched the training session. There were plenty of accomplished swimmers, female as well as male, Jordan the unassuming star. Greg watched as he stood poised to dive, then the deep, clean swoop. In the water he was streamlined and powerful, somersaulting into a tumble-turn, swimming length after length of crawl, back crawl, and—his speciality—butterfly.

‘You ought to join the club,’ he had told Greg. ‘We could do with more people in the team. What’s your best stroke?’

‘Front crawl. But by

best

I mean least bad. You’ve seen me—I can swim for miles but I’m never going to win races. You’d leave me standing.’

Jordan was preparing now for county trials. When the other swimmers finished their session, the coach kept him a little longer to work on the butterfly. It looked so easy, done properly: as if the water itself were gathering its forces to hurl the swimmer along the surface. Humped back, head tucked in, water showering from arrowed arms, water gleaming on skin; then the darting precision of the turn, the thrust underwater, the renewed power of the stroke. Wonder if I could photograph that? Greg thought. Would the digital camera have a fast enough shutter-speed? Keeping in mind David Bailey’s comment about noticing the ordinary, he was building up a second sequence of pictures, taken at the pool. Watery images: the unbroken surface when the pool was empty; the steps dropping into turquoise clearness; the clean-ploughed wash from a strong swimmer. He wanted underwater shots too, if he could find a way of getting them.

Paul, one of the staff, came to take over at the poolside. ‘Fantastic, that.’ He jerked his head towards Jordan in the pool. ‘Our Olympic hope.’

‘You’re joking!’

‘Probably. Pretty damn good though. Wish I could do butterfly. All I do is make tidal waves and half-drown myself.’

‘Same here.’

Greg went into the changing room to get out of his shorts and T-shirt and into school uniform, taking his time. When he came away from the locker, bag slung over his shoulder, most of the swimmers had gone. Jordan was standing under the shower, his back to Greg; his trunks, towel and goggles hung on a hook. He was rinsing his hair, arms upraised, head tilted back, foam sliding between his shoulder-blades. Greg stopped, looked, took in what struck him as beautifully photographable: the light, the spray, the lovely curves and angles.

Frame, click

went his mental camera. Jordan turned; saw him, and smiled.

‘Hi. Are you biking in? Ready in a couple of minutes if you don’t mind hanging on.’

‘OK,’ Greg said. He went to the mirror and tidied his hair. It was tidy already, but he needed to hide his confusion. Jordan had seen him standing there, looking, looking, a little more intently than was permissible, and did not know it was with photographic intent.

After History, Greg stayed behind on the pretext of explaining to Mrs Hampson that his homework wasn’t in because the computer’s ink cartridge had run out. She waved aside his excuses, picking up her pile of books. ‘Tomorrow will do. Such is my faith in human nature that I’m prepared to believe you.’

‘Actually, I wanted to ask you something. You know the First World War?’

‘Greg, I’m a History teacher.’ She dumped her pile back on the desk. ‘I may have heard it mentioned once or twice.’

He ignored the sarcasm. ‘You know how people got shot by firing squad for deserting? If that happened, would they still be buried in the proper war cemeteries?’

‘Oh yes,’ Mrs Hampson said. ‘In fact there’s been a lot of controversy recently—you may have heard about it. Whether the records should be put straight now that we know about shell-shock and war neuroses. I’ve got a book if you’d like to borrow it.’

‘Thanks. The gravestone inscriptions wouldn’t say anything, would they—about the men being executed?’

‘No. They’d have exactly the same style of wording as all the others. Just the regimental details and date. Hang on—I’ll get that book from my office.’

It took her a few minutes to find it. Jordan was waiting outside in the corridor; they’d be a little late for their next lesson. Greg shoved the book into his rucksack, and they walked together to the Maths block on the opposite side of the campus. This took them past the staff car park and through the area behind the kitchens where the recycling bins were kept, a couple of storage sheds blocking the view from the main building. A group of Year Nines loitered there, smoking. Most younger boys would have scarpered if two sixth-formers came along, but not these: with a sense of inevitability Greg recognized Dean Brampton and friends. Dean stood firm, eyeballing Greg. Yusuf, who had made a move towards the recycling bin, saw that Dean wasn’t giving way and put on a tough pose.

‘Oooh, look who it isn’t! Hobb-Knobb! Thinks he’s hard,’ Dean said loudly, then spat at the ground.

‘Hard Knob!’ Yusuf gave Dean a shove and lurched about with exaggerated laughter.

‘If you want to carry on walking about in one piece,’ Greg said, ‘you won’t touch my bike again. Go anywhere near it and I’m calling the police.’

‘Who says we touched your poxy bike?’ Dean jutted his chin at Greg. ‘You grassed us up to Rackley. We’ll get you back, don’t worry.’

‘Have you got all day to stand round being unpleasant?’ Jordan asked. ‘No lesson to go to?’

‘What’s it to you, tosser?’ Dean flicked his cigarette end at him. Jordan, not used to getting into arguments with mouthy Year Nines, sidestepped neatly and made to walk on.

‘You grassed us up,’ Dean repeated, thrusting his face at Greg. ‘You’ll be paying for that. And soon.’

‘What d’you expect if you do criminal damage for kicks?’

The smaller boy, the least aggressive of the three, was looking towards the gym. ‘Mad Mitch,’ he warned. ‘Coming this way.’

Mr Mitchell, one of the PE teachers, was merely standing outside the building waiting for the Year Nine footballers, but the sighting was enough to make Yusuf fling down his fag and for even Dean to amble off.

‘Better run along,’ Greg said to Dean.

He waited for the parting taunt and it came, hurled at him over Dean’s shoulder: ‘You’re gay!’

Greg looked at Jordan. ‘As if!’ It came out too loudly.

Jordan made no response. He swivelled the toe of his boot on the glowing fag end and asked, ‘Why’ve they got it in for you?’

‘Morons like them don’t need a reason.’ Greg was more angered by the incident than he felt was dignified. Dean Brampton got to him every time. Yusuf was a pain, the fair boy was just a sidekick, but that Dean—the way he stared with utter contempt—brought out aggressive instincts Greg didn’t know he had. And this latest tactic—

you’re gay

. . . Kids threw that about all the time as an insult, Greg knew that. ‘You’ve nicked my pencil case! You’re gay’—it was meaningless. All the same, he didn’t like it. ‘Forget them,’ he said to Jordan. ‘They’re not worth it.’

‘But they did your bike in! We could shop them for smoking?’

Greg shook his head. ‘They’d have to knife someone before the Head would get off his backside. Anyway, it’d only make them worse.’

‘Be careful, though,’ Jordan said. ‘Trouble waiting to happen, they are.’

Mrs Hampson’s book

Shot at Dawn

had an index listing all the First World War soldiers executed for cowardice or desertion. E. Pearson was not among them. Indeed, Greg would have been surprised to find him; if he’d been there, he’d also have been on the Commonwealth War Graves website. Some of the tales were appalling—men with nerves shot to pieces being dragged before firing squads, and even one account of a boy being executed while he was still too young to have legally enlisted. Greg was relieved that Edmund Pearson had been spared such a fate. Perhaps Faith’s researches had been more fruitful.

She rang him that evening. ‘Meet me after school tomorrow?’

Greg didn’t want her turning up at the gates again. ‘Where?’

‘Where we went last time? The Casa Veronese?’

‘OK. See you there then, at the CV, round four.’

The following day he parked his bike and stood outside the Italian restaurant to wait for her. A brisk tapping on the glass surprised him, and he turned to see her already seated inside, chatting to the waiter. As soon as Greg went in, the waiter went back to the kitchens, as if they were young lovers desperate for privacy. But they weren’t alone this time; there were two other customers, women with carrier bags full of shopping, who sat at the table nearest the back.

‘Well?’ Greg said. ‘Did you find something?’

Faith gave him a reproving look. ‘Hello, Faith, how lovely to see you, and have you had a good day?’

He grinned. ‘Yeah, yeah, that as well.’

‘You’re really into this hunt for Edmund Pearson, aren’t you?’

‘Thought you were as well.’ If she was going to start being difficult, he might as well order something. He was ravenous; he snatched up the menu to see if he could afford anything to eat.

‘Well, yes,’ Faith conceded. ‘I am, now. You’ve got me intrigued. I’ve already ordered, by the way. Cappuccino, OK?’

Greg nodded. ‘Are you going to tell me, then?’

She took a notebook from her school bag. ‘We didn’t find much. Births, yes. Edmund Henry Gibbs Pearson, eighteenth of March eighteen ninety-six, Graveney Hall, son of Henry Gibbs Maynard Pearson and Elizabeth Mary Pearson. Baptized thirtieth April. No wedding. No death.’