Read The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace Online

Authors: Jeff Hobbs

The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace (26 page)

But they were not over, not quite yet. We still had one more ceremony the next day, when the graduating seniors from Pierson College gathered in the college quad to receive our diplomas. We filed in from the slate patio on which we'd first gathered almost four years earlier. Then, Rob had been smoking a cigarette off to the side in his Timberland boots, looking older than the rest of us. He didn't look that way anymore. Maybe in our matching navy gowns and tasseled hats, anyone would be hard-pressed to look very mature. Maybe the rest of us had caught up with him somehow, though I doubted that. Maybe we all knew him now, some very well, and so the isolationist attitude with which he'd first approached campus no longer manifested. Or maybe, most simply, he couldn't withhold a boyish smile that day.

Twenty, maybe twenty-five of his friends and family had come up for the day. Aunts and uncles, cousins, neighbors, friendsâthey'd all packed themselves into a procession of four-seat cars and caravanned up to New Haven. In their center were Frances and Jackie. Jackie sat beside her mother's wheelchair, both of her hands stacked upon ÂFrances's on the armrest. The dean read each of our names from a small lectern to the right of the stage, while the master gave out diplomas in the center. When she said, “Robert DeShaun Peace. Bachelor of science in molecular biophysics and biochemistry, with distinction in the major,” a cacophony of

whoop-WHOOPS

broke out from his cheering section in the rear of the tent. Rob took his time mounting the stage. With his left hand on Rob's shoulder, the master handed the diploma over with his right, and the two men lightly hugged one another, and the hooting behind us reached a crescendo to the point where the more reserved parents and students (meaning about 90 percent of those present) began

turning their heads: faces calibrated to amusedly share in the joyfulness even while, in their minds, some had to be wondering why such people couldn't contain themselves a little bit more respectably. Then Rob was at the microphone on which the master had made his opening statements. He cleared his throat, a signal for his section to calm down. The heat-trapping tent grew quiet.

He glanced at a scrap of paper in his hand, pocketed it, and said, “A Yale education encompasses more than classes; it is the experience that has better prepared me for life. I would like to thank all the people who supported me in this endeavor, and I dedicate this moment to my motivation and heart, my mother.”

I expected the audience, led by the New Jersey contingent, to break into cinematic applause. But for a few moments, everyone remained silent and still. The clapping and cheers, when they came, were brief. Ty shouted,

“

Peace OUT!

”

and we all laughed. Then Rob returned to his seat between us.

I don't recall much of the day after that, no doubt because it revolved around more drinking, more parties. People I'd barely known or openly disliked would stumble up to me and drape a bear hug over my shoulders, slurring exclamations like, “We did it!” and “We survived!” At one point I went back to our room, half cleared out at this point, just to take a breather. Rob was there, also alone, rolling a joint on our coffee table with that precious way he had. He offered me a hit. I shrugged, sure. We sat and got stoned, maybe for fifteen minutes or so. We must have talked, but about what I will never remember. Most likely, we just bullshitted without much allusion to the fact that this was it. College was over. On to the next thing, whatever that was. These moments, our last as roommates, were very calm.

I woke early the next day and, hungover, packed the last of my things. I knocked lightly on Rob's door to say goodbye; he wasn't there. Dio, his python, was coiled up in the glass tank atop the black trunk, still digesting a vermin eaten five or six days earlier. Textbooks were piled up

in the corner to be sold back to the Yale Bookstore. Two duffel bags in the center of the floor were half packed with clothes. The pictures of the Burger Boyz at 34 Smith Street and Jackie at St. Benedict's graduation had been pulled down. The incense he'd burned couldn't fully mask the smell of stale marijuana; over the years, I'd grown fond of that smell, the vestiges of good times that had clung to curtains and carpeting: the smell of my friend.

I didn't wait to say goodbye to Rob. I figured that the nature of our friendshipâthe nature of Rob himselfâdidn't necessitate that final ceremony after all the ceremonies we'd already endured: the man hug, the firm-grip-thumb-lock-hand-clench-half-hug, the not-quite-tearful “Later on, man.” Rob was cooler and easier than that, and he wasn't going anywhere. There would always be time, I thought.

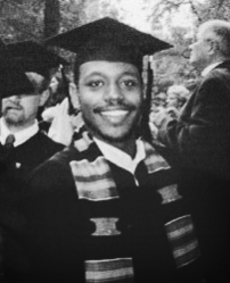

During Yale graduation weekend in 2002, Rob wore the African scarf that he'd been given during the “Black Graduation” ceremony one week earlier.

Part IV

Mr. Peace

Ty Cantey (second from left), Rob (third from left), and I (third from right) had a roommate reunion when they served as groomsmen at my wedding in Brooklyn, 2005. Later in the night, we three “Threw Dem Bows” on the dance floor.

Chapter 9

H

E WAS AMAZED

by what had been left behind. Expensive winter coats, racks filled with CDs, textbooks, halogen lamps, six-Âhundred-thread-count sheet sets that had never been unpackaged, gold and silver jewelry, stereos, Discmans, and even laptop computers: graduated seniors had simply departed without these things. And Robâwho was working the summer custodial job for the fourth straight year, cleaning up the campus between graduation in mid-May and the alumni reunions in early Juneâstayed to sweep it all up. He dealt with items of value first, stashing anything sellable in an industrial garbage bag that he set aside. Then came the work of hauling abandoned furniture down the stairs, sweeping up all the dust and grime and hair that had accumulated over the year, mopping and painting, reconstructing bunk beds that had been pulled apart in room after room. The various spaces he'd inhabited over the years were now empty, given a clean coat of white paint, awaiting next year. We'd all come to Yale aiming to leave a footprint; Rob knew from this work that none of us had, at least not in the dorm rooms.

He took a lot of cigarette breaks alongside the full-time maintenance employees, men he'd befriended over the years. They were generally derisive of the students, the way they felt entitled to just

leave their shit

for others to pick up. Dozens of fifty-gallon trash bags' worth of said shit lay in a mountain in a corner of the quad, next to the master's house. The final task was to transport them to a Dumpster on Park Street before the last debris of our time here was hauled away.

They did sell the valuables they'd collected. Like every year, the six-person custodial team combined what they'd found into one cache of contraband. First, they sold the textbooks back to the bookstore, which paid a fraction of the cover price no matter the conditionâbut still, it was cash. As for the rest, each member helped unload what he could. Some used the Internet. Others pounded the pavement in their neighborhoods. Afterward, trusting one another's honesty, they divided the profits evenly. At the end of the three-week stint, Rob came away with almost $1,000. The figure paled in comparison to the money he had already saved. But still, he made enough to cover the summer's rent in New Haven. He also gave himself a graduation present in the form of a second tattoo, this one on his left biceps, of an African woman with a tall headdress seen in profile. The image matched exactly Jackie's lone body art, inked during her twenties, before Rob was a thought.

He remained on the custodial staff during the reunions in early June. A few thousand alumni from as recently as five years ago and as far back as the 1950s caught up beneath tented open bars and catered food spreads. The schedule included lectures and three-course meals and various activities like group hikes up East Rock and tours of the botanical greenhouseâbut the guests (the older they were, the increasingly white and stodgy and male) mostly hung out and drank, like they'd done in college. Rob moved around the fringes of the various gatherings, emptying the trash cans and picking up the plastic cups, napkins, and spilled food. Like the very first week of school, nobody looked at him and assumed he was anything other than a janitor. Unlike the first week of school, he was one.

After the reunion cleanup was complete, he went back to work in the med school lab, where he assisted in researching the pharmacology of proteins that led to infectious disease, inflammation, and cancer. His primary focus was on the structural biology of chemokinesâprotein receptors secreted by cells to recruit an immune response to the site of an infection. Using X-ray crystallography, Rob spent the summer and fall isolating the CXCL12 (SDF-1alpha) and vMIP-II/vCCL2 chemokines

for the GPCR CXCR4 coreceptor for HIV-1. This particular receptor also mediated metastasis in a number of cancers, as well as a mutation responsible for an immunosuppressive disease known as WHIM syndrome. The applications included stem cell transplantation and the production of medicines to halt the takeover of these afflictions. In our dorm room, we had always joked admiringly about the fact that Ty Canteyâwho was now preparing for a yearlong fellowship at Cambridge, England, before undergoing a seven-year MD-PhD program at Harvard Med Schoolâwas destined to cure cancer someday. I had no idea that Rob, in the lab he'd walked to almost every day during junior and senior years, was actually helping to do it.

He lived with Raquel, in a basement apartment near Jacinta's that they called “the dungeon.” The apartment was relatively small, especially for a man and a woman who were not romantically involved. The only windows were at the top of the wall, giving them a view of the calves and ankles of passersby. A gigantic hammock was strung across the high ceiling in a makeshift loft, for storage and, on occasion, amorous escapades. They kept their clothes in plastic containers and cardboard boxes. In lieu of paint that they didn't want to pay for, Raquel decorated with bohemian shawls and tapestries from her travels. Their home was not unlike a college dorm room, and their day-to-day lives were not unlike college in that they felt transient, based on their work and social lives outside the domicile. And yet, within it, they found themselves playing the roles of husband and wife. Rob came home from work and Raquel would have dinner on the table, huge spreads of Puerto Rican fare, stewed pork or chicken sweetened with plantains and agave nectar, ladled over a bed of yellow rice. Over the meal, they would talk about their days, often wearily, completing one another's sentences. Mostly, Raquel did the talkingâthe custodial job being too banal for Rob to bother getting into, the lab work too complicated. She was stressed about having skipped a year, the financial and social task that lay ahead, the fact that she would be finishing school alone since most of her friends had left and were already beginning their lives. Rob would calmly tell her to put her head

down and do what she needed to do to get through it. He would tell her that he was her friend; she could rely on him.

Perhaps in all of his various and diverse social circlesâthe stoners, the scientists, the Burger Boyzâhe was most comfortable in this role: sitting across from a female friend and passively permitting her to depend on him, to transfer her anxieties onto his shoulders the way his own mother rarely let him do. He was skilled at making a woman feel taken care of, and this knack had caused trouble before. Senior year, he'd been at the house Daniella Pierce shared with her boyfriend, Lamar. She was making dinner and had trouble opening a jar. She brought it to the living room, where Rob and Lamar were talking, and gave the jar to Rob. He opened it easily and assured her that she must have already loosened it up for him. They had a nice dinnerâDaniella had become heavily involved in social work in the New Haven community, particularly in helping teenagers with police records finish high school, and Rob would listen to her catalog the alarming statistics for hours. After dinner, Rob left, which was when Lamar erupted at her with genuine outrage.

“What'd you give him the jar for?”

“Excuse me?” Daniella asked.

“The jar. You gave it to Rob to open it. I live here. I'm your man.

I

should have opened the jar.”

“That's ridiculous,” she replied, but even then she began thinking about how instinctively she had given Rob the husband's task. “You're crazy.”

The intensity of the interactionâthe visceral anger Rob was able to inspire in another manâamazed her. If Rob was aware of the effect he could have, he didn't show it. He did spend much of his time with women who were involved with others. He did encourage them to open up to him in ways they never would to their actual boyfriends. Sometimes he would do this in the presence of those boyfriends. He didn't seem to think twice about it, and he'd never made advances on a “married” woman. In exchange, these women braided his hair for him, watched kung fu movies with him, and cooked for him (Rob would

never pass up a free meal). Generally, aside from a few episodes similar to the one with Lamar that could be brushed off as overreaction, he considered himself cool with the boyfriends. By all appearances, he remained ignorant of the fact that, over time, an increasing number of men, primarily black, began talking behind his back, calling him arrogant, calling him cheap, calling him a nigger.

“There are niggers, and there are brothers,” Rob had told me once, lightly. He was referring to a song that was so peppered with the word that it made me fidget. Simply hearing the

n

word set off all sorts of alarm bells in a white guy; though Rob was grinning and clearly enjoying this teachable moment, I knew I had to be careful about everything from my responses to my expressions to my hand gestures. Under no circumstances could I say the word myself, nor could I act as though I understood anything Rob said regarding the word.

I replied with a ponderous

huh

.

“Niggers just like to start shit,” he said. “They don't value human interaction, let alone human life. They're just stupid, period. They walk around, trying to act hard, trying to be bangers”âin Newark parlance, “bangers” was pronounced as two separate syllables:

bang-gers.

“That's all a nigger cares about: acting hard. Fronting.”

“What about the brothers?” I asked. This word felt much safer.

“A brother's like me. He just wants to take care of his own and chill.”

And during the summer and fall after graduation, that was pretty much what Rob Peace did. And even though he drove down to Newark every weekend, Jackie was not pleased.

The last four years had been the hardest of her life. She'd worked, she'd taken care of her ailing parents, she'd spent money as fast as she'd earned it on only the essentials. For the first time in her life, she'd been alone. The struggle that felt inseparable from the place and circumstances of her birth was primarily leavened by companyâthe big families, the stoop culture, the social gatherings outside liquor stores. But Jackie wasn't like Skeet; she rarely ventured beyond the daily rhythms of home and work. The only leisure she allowed herself was the occasional

trip to Atlantic City, where she played slots, sitting alone in a bank of strangers, pulling that crank again and again until the skin of her hand began to dry out and crack. If she couldn't find a room for less than $30, she would drive there and then drive home. Otherwise, during her relatively few free hours, she sat on the porch and smoked. Frances would be inside watching TV, hooked to her oxygen tank, and Horace would be shuffling around. Jackie would sink deep into the Adirondack chair facing the vacant lot across the street, maybe exchanging a few words with a passing neighbor while projecting her preference for silent solitude. She would think mainly of Rob, at Yale. Landing her son at such a place had been her life's primary goal, and yet the essence of that place had always escaped her. Yale, to her, was a corridor between stations, not a place with a pulse. She didn't care much about the dynamics of living there, and when Rob visited during college, he spoke of those dynamics hardly at all. Lacking the information necessary to ponder what he was doing in New Haven, she thought instead of what he would be doing when he left.

From what she could tell, after graduation he wasn't doing much. She figured that the lab work was good for him, but the only path it laid out would be toward more school, and if there was going to be more of that she didn't understand why he seemed reluctant to get his education over with and settle down. Victor, to her, set the example: he'd gone to school in order to learn to fly, and now he was doing just that in the Air Force Reserve. The only goal her son seemed to talk about was Rio. He appeared to have some vague plan of establishing a scientific career there. Jackie didn't know much about Rio, but she knew that the city was famous for parties, drugs, samba, poverty, robberies, and not science. Each time he left for New Haven, she would find a few hundred dollars in cash on the counter, the same spot he'd once left four or five dollars. She'd never asked for money. She didn't depend on it, though it certainly helped. She chose not to wonder where it came from. Because he never left more than he seemed able to afford from his lab work, this was easy to do. And yet something about these billsâmaybe the

haughty way he fingered them out from a roll of cash, like a real operatorâworried her.

She was also worried about him leaving the house when he was home. She hadn't experienced this anxiety since he'd been a boy, and even then she hadn't worried much, because he'd usually been with his father, or with friends to look out for him. During Rob's college years, as Jackie watched from her perch on the porch, a sea change had overtaken the surrounding blocks in the form of gang violence. When Rob had left for college in 1998, there had been a few loose formations that could have been construed as gangs, mostly brought together by geographical proximity; young men had always been territorial about their neighborhoods and their drugs, and the resultant conflicts had caused most of the violence in Newark during the first two decades of Rob's life. But those threats had also been relatively easy to navigate: you knew where the boundaries were, you knew where the dealing centers were, and you steered clearâor else you made sure you knew the right people; you Newark-proofed. But when Rob graduated from Yale in 2002, there were more than a hundred gangs operating in Essex County, and these gangs, these terrible loyalties, were based on people rather than places. People were more dangerous, less predictable, less clearly demarcated. The Sex Money Murder Bloods, the Nine Trey Bloods, the G-Shine/Gangster Killer Bloods, the Grape Street Crips, the 5-Deuce Hoover Crips, the Double II Set Bloods, the Rollin 60s Crips, the Fruit Town Brims, the Latin Kings, Ãeta, the Pagan's Motorcycle Club, MS-13âthey were defined by colors, obscure symbols graffitied on walls (some of these quite artful), and rituals that had no clear cause or limits. The most powerful entity in East Orange was the Double II Sets, a group that had been “incorporated,” so to speak, when a contingent of the Queen Street Bloods relocated to East Orange from Inglewood, California, in the mid-1990s (the “II” in the name referenced the “ll” of “Illtown,” a nickname for East Orange). With them, they'd brought some of the practices and traditions of the West Coast Bloods, most notably a merciless treatment of disloyalty within their ranks.