The Silk Thief

Authors: Deborah Challinor

This one is for my beautiful great-nephew, Oscar Jack Anderson, born on 16 January 2014

Contents

Part One: When the Melancholy Fit Shall Fall

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Part Three: And Drown the Wakeful Anguish of the Soul

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Other Books by Deborah Challinor

When the Melancholy Fit Shall Fall

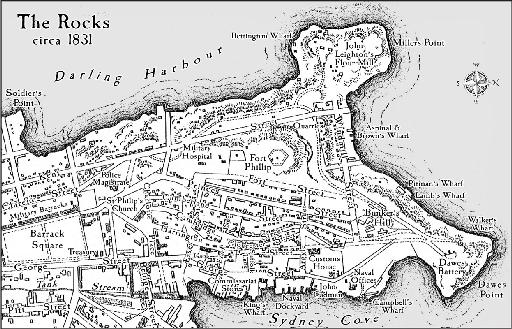

Early Monday morning, 11 July 1831, Sydney Town

Harrie Clarke hadn’t slept at all well. She’d tossed and turned, worry nipping at her like a hungry rat, her dreams getting as twisted as her sheets; and when Angus the cat had come in he’d selfishly spread himself across half the mattress. And now someone was tapping on her window. Except that was impossible — her room was high up in the attic.

Grateful for the rag rug on the cold floorboards, she crossed to the window and peered down past the shingled slope of the roof. Dawn was still several hours away and there was hardly any moon — she couldn’t see a thing. During the day her eyrie at the top of the Barretts’ two-storey house afforded her a view of the roofs, privies and dank yards of those who lived below on Harrington Street (and, unfortunately, of the gallows within the walls of Sydney Gaol), of the streets of the town to the south and west, and of Sydney Cove and the governor’s enormous private gardens to the east. Now, however, in the velvet darkness, her ears and nose were more use to her than her eyes. She heard the susurration of small waves on the cove’s shore, the strident call of a night bird and the tuneless singing of a drunk somewhere down near George Street. As always, the nearby cesspits tainted the air even up here, undercut by yesterday’s rendered tallow from the soap and candle works in the next street, mixed with wood smoke from hearth fires and the pleasant briny tang of the sea.

But as her eyes adjusted to the night’s shifting shadows, she made out the barest outline of a lone figure standing below in the backyard, its pale face turned up towards her. A raised arm drew back and something small and hard bounced off her window, making Harrie flinch. A pebble?

Her visitor was a boy, and she guessed from the way he held himself it was Walter Cobley. But what had gone wrong, to make him rouse her so early on a Monday morning? Had something happened to Friday in the night? No: Walter knew nothing about her gruesome midnight errand.

Harrie lit the bedside lamp, keeping the flame low. Angus, awake now, gave a soft meow as she slid her feet into slippers. The air was chilly but she didn’t bother with a robe. She made her way downstairs, treading gently on the creaky risers so she wouldn’t wake anyone, and let herself out through the back door.

He was waiting for her, his lanky form detaching from the yard wall as though he were made of smoke.

She whispered, ‘Is that you, Walter?’

‘I need help, Harrie.’ His voice cracked and he cleared his throat, the sound close to a sob. ‘I’ve done something bad.’

She lifted the lamp, and almost dropped it. Walter’s shirt, jacket, face and hands were splattered with some dark substance.

‘Walter! Is that blood? Are you hurt?’ She took a step towards him, but his scruffy little dog, Clifford, crouching protectively in front of him, growled menacingly.

‘Shut up, Cliffie. It’s not mine. It’s Amos Furniss’s.’ Walter swallowed audibly and stared down at his hands — held before him palms up, fingers spread — as though they belonged to someone else. ‘I killed him, Harrie.’

Her heart stopped, then lurched into a wild, thumping rhythm. ‘Amos Furniss? You’ve killed Amos Furniss?’

Walter nodded.

‘But … where?’

‘In the old burial ground.’

Harrie went dizzy as the enormity of what he’d done overwhelmed her. She was confused, too — Friday had gone to the cemetery, not Walter. She had the most hideous thought. ‘Is Friday all right?’

‘I suppose. I dunno.’ Walter wiped a trembling hand over his face, smearing tacky blood across his cheek.

‘What do you mean?’ Desperate to hear about Friday, she wanted to grab his shoulders and shake a useful answer out of him, but he was clearly suffering from shock and she knew it wouldn’t do any good. ‘What happened, Walter? Tell me.’

Walter squatted so suddenly Harrie thought for a second he’d collapsed. But he was only crouching to pat Clifford, his blood-sticky hands running along the dog’s hairy back, drawing in comfort stroke by stroke.

‘I followed her to the burial ground.’

‘Friday? Or Clifford?’ she asked. Clifford was actually a bitch despite her masculine name, and Harrie wanted to be very clear about who was who in Walter’s story.

‘Friday. And I seen Furniss so I hid while she gave him the money. Then when she’d gone I followed him to the Bathurst Street gate and I stabbed him. To death.’ He raised his head, his teeth bared in something not even close to a smile. ‘And I’m bloody glad I did, Harrie. He deserved it.’

She nodded: she knew why Walter had killed Furniss. The shock of his news had for some reason heightened her sensory perception — she could taste the cold in the air and feel the darkness on her skin, and she fancied she could actually hear the bones in her neck grating together. She shivered.

‘And I thought I’d feel … I dunno, happy or something,’ Walter said. ‘But I don’t. I feel funny. I feel sick.’

As if to demonstrate this, he retched and, narrowly missing Clifford, heaved up a little puddle of watery vomit.

Harrie patted his back as he spat out a long string of saliva, and this time Clifford didn’t growl at her proximity. This close, Walter smelt like a freshly slaughtered cow and she felt her own gorge rise. ‘Where’s Furniss now?’

‘Still at the burial ground.’

Harrie waited until he’d spat some more and wiped his mouth on his sleeve. Then she said, ‘Walter, listen to me. Did anyone see you leave? Or on George Street near the burial ground gates? Is that the way you came here?’

He shook his head. ‘I come back along York Street.’

‘But did anyone see you?’

He shrugged and settled his hand gently on Clifford’s head. She licked his mucky fingers. ‘Maybe,’ he said. Then he nodded miserably and started to cry.

Harrie dressed hastily, not caring that her shift was on backwards, and wrapped her shawl around her shoulders. She glanced at the rocking chair under the eaves, but it was disappointingly empty. She felt sick, and a leaden, almost painful, sense of doom had settled in her belly.

She’d despised Amos Furniss herself, but now there’d be another dead soul to creep around in her mind and torment her. Liz Parker and Gabriel Keegan, then Jared Gellar and now Furniss. And poor, darling Rachel, of course, though unlike the others she’d been a tremendous comfort since she passed. So many folk whose paths she and Sarah and Friday had crossed had died. Is it us? she wondered. Are we somehow responsible for all those deaths? Am I?

She crept back downstairs. Walter was still there, hunched against the wall in a crouch, head resting on his arms, Clifford at his feet. The dawn was still a good hour or so away. Harrie knew she’d have time to get to Friday’s, then Leo’s, then back again before the Barretts awoke.

‘Come on.’ She offered Walter a hand up. ‘Let’s get you home. Leo’ll know what to do.’

Walter extended his own hand; in the light of Harrie’s lamp they both eyed the blood staining his skin and the rims of his fingernails. He withdrew it, and pushed himself off the cobbles.

‘Quickly, love, have a wash.’ Harrie indicated the bucket beside the rainwater overflow barrel, and wondered why he hadn’t done so already. The shock, probably.

‘I lost me hat,’ he said forlornly.

‘Never mind, we’ll get you another,’ Harrie said, as though she were talking to a five-year-old.

Walter splashed his face with cold water and scrubbed at his hands while Clifford helped herself to a noisy drink from the bucket.

‘Why did you come here?’ Harrie asked as they hurried along Gloucester Street towards the turn into Suffolk Lane. Worried that someone out early would see the state of Walter’s clothes, she’d given him her spare shawl to wrap around his shoulders. ‘Why didn’t you go straight home?’

‘Oh.’ Walter stopped, dug around inside his jacket and brought out a pouch. ‘This is for you.’

Harrie didn’t have to look inside to know what it contained. Her heart sank yet again. ‘The money?’

He nodded.

‘How did you know to follow Friday last night? How did you know who she was meeting?’

‘I were listening when you and her were talking about it at Leo’s,’ Walter confessed. ‘When she were getting her new tattoo?’

Oh God. Harrie felt as though her insides were turning to water. After all these months, was their secret finally out? What had she and Friday said that day? She really couldn’t remember. She was having trouble remembering all sorts of things lately. Nervously, she asked, ‘What, exactly, did you hear?’

‘Friday said something about Bella and two hundred quid. And that the money were to be delivered to Furniss at the old George Street burial ground last night. At midnight. And something about a lady called Janie and some babies missing out? You said you haven’t got much money to give. So I got it back for you.’

He didn’t appear particularly pleased with himself — unsurprisingly he still looked like a boy shocked silly after stabbing a man to death — but Harrie knew him well enough to understand that he needed acknowledgment for retrieving the money, whatever other awful thing he’d done. So she said, ‘I’m grateful for that, Walter. We all are. Thank you.’ Though there would be hell to pay when the blackmail money remained undelivered and Bella discovered that Furniss was dead. She would immediately assume that Friday, Sarah or herself had killed him. Bella already knew, after all, that they were capable of murder. God, why hadn’t Walter thought of that? But he was only a boy.

‘Walter, when Friday and I were talking, did we say why we were being blackmailed?’