The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (16 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

o one loves a broomstick quite like a

o one loves a broomstick quite like a

witch

. Harry’s great affection for his Firebolt makes it tempting to include

wizards

in this statement as well. Historically speaking, however, almost every person reported to soar through the sky on a broom was a woman. When the occasional wizard or warlock did lay claim to flying skills, he was more likely to travel on a pitchfork!

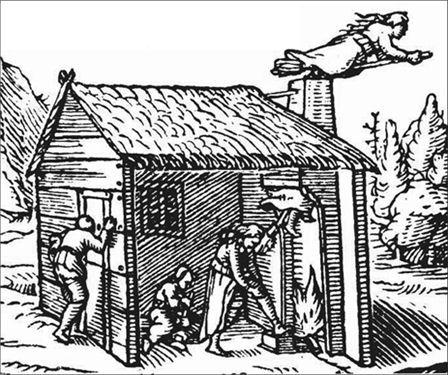

Although popular illustrations today invariably show a broomstick as the witch’s mode of transportation, this was not always the case. Between about 1450 and 1600, when belief in the power of witchcraft was widespread in Europe, witches were reported to take to the skies and head to their midnight gatherings astride goats, oxen, sheep, dogs, and wolves, as well as on sticks, shovels, and staffs. Broomsticks ended up as the preferred vehicle, some scholars suggest, because of women’s traditional role as housekeepers.

According to popular lore, much of it invented and circulated by professional witch hunters, witches usually left their homes via the chimney. Once airborne, flying was said to be relatively easy—except in two cases. A novice witch might have trouble staying on her broomstick, which was likely to be swift but unstable. Additionally, witches could be brought down—or prevented from taking off—by the sound of church bells. In the early seventeenth century a town in Germany was so fearful of witches on broomsticks that for a time the city council ordered all churches to ring their bells continuously from dusk to dawn.

Witches were reputed to rub “flying ointment” on their skin before leaving through the chimney for their midnight gatherings

. (

photo credit 8.1

)

Whether witches could really fly was a subject of serious debate among scholars and religious authorities, especially during the most intense years of

witch persecution

. According to the

Malleus

Maleficarum

(1486), the most popular guide to the discovery and punishment of witches, flying was an incontestable fact. For one thing, many women had confessed to flying, and some had even boasted of their ability to take to the air. Furthermore, a passage in the biblical Book of Matthew described Satan’s power to transport Jesus through the air. If the Devil could make Jesus fly, some churchmen pointed out, he certainly could bestow that ability on the witches who served him. Other scholars rejected the notion of flying as a physical impossibility and argued that the Devil merely caused women to

think

they had flown by filling their heads with delusions.

A more scientifically minded group of thinkers offered yet another explanation. Witches were known to prepare for takeoff by rubbing their brooms and their bodies with a special “flying ointment” made of plants and herbs (among them henbane,

mandrake

, monkshood, and belladonna) grown in their gardens. Physicians who experimented with flying ointment in the sixteenth century found that it contained powerful chemicals that entered the body through the skin and caused deep sleep and hallucinations—including a sensation of flying. As they explained it, witches who believed they “flew” actually fell asleep in their own kitchens and awoke with vivid memories of a fantastic flight that had occurred only in their

dreams

.

enign as old, gray Mrs. Norris might appear to an outsider, no Hogwarts student can quite feel comfortable in the presence of Argus Filch’s pet cat. She’s always on the lookout for bad behavior, and she seems to have an uncanny ability to share information with her master without so much as a meow.

enign as old, gray Mrs. Norris might appear to an outsider, no Hogwarts student can quite feel comfortable in the presence of Argus Filch’s pet cat. She’s always on the lookout for bad behavior, and she seems to have an uncanny ability to share information with her master without so much as a meow.

Cats have long been associated with

magic

and the supernatural. In the sixteenth century, they were widely known as the companions of

witches

and, like Mrs. Norris, were suspected of being able to communicate with their owners. In parts of Scotland, this belief was so strong that many people refused to discuss important family business when a cat was in the room, for fear that what they revealed would later be used against them by a witch.

According to some theories, however, cats were more than just witches’ spies—they were actual witches in disguise. Nicholas Remy, a sixteenth-century judge who presided over hundreds of witchcraft trials, claimed that almost all of the witches he had come across easily transformed themselves into cats when they wished to enter other people’s homes. But unlike Professor McGonagall, who can turn herself into a cat as often as she likes, historical witches were said to be able to perform this feat only nine times—once for each of a cat’s reputed nine lives.

The most common role for a witch’s cat was that of

familiar

(see

witch

). More servant than pet, a familiar was reputedly a minor

demon

, provided by the Devil to do any evil errand a witch might devise, from souring milk to destroying livestock to bringing chronic illness or even death to her enemies. In one sixteenth-century trial, a confessed witch claimed that her cat, Sathan, spoke to her in a strange hollow voice, found her a wealthy husband, caused him to go lame, and murdered her six-month-old baby at her command. In western England, witnesses claimed to have seen a woman known as “the Wicked Black Witch of Fraddam” riding through the air on a huge black cat whenever she went looking for poisons and magical herbs. With stories like these running wild, it’s not surprising that people were as terrified of cats as they were of witches, and treated them every bit as badly.

Before cats were feared, however, they were revered. The ancient Egyptians were the first people to keep cats as pets, and eventually cats became the object of religious devotion. It began about 2000

B.C.

, when the goddess Bastet, usually portrayed with the body of a woman and the head of a cat, was worshipped as the personification of fertility and healing. According to the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, cats designated to live in temples were pampered with meals of bread and milk and slices of Nile fish, and even their caretakers had high status in the community. Eventually all cats came to be regarded not merely as symbols of Bastet’s goodness but as gods themselves. Killing one, even by accident, was punishable by death, and when the family cat died of natural causes, everyone in the household shaved their eyebrows in mourning. Cat

amulets

were made and sold by the thousands. And reverence toward cats didn’t end when they died. It was important to bury a cat with the greatest respect, which in those days meant wrapping them as

mummies

(mummification was believed to enable the dead to return to life). In the summer of 1888, an Egyptian farmer digging on his land unearthed a group of 2,000-year-old cat mummies lying just under the desert sand—300,000 of them! This proved to be only one of many ancient cat cemeteries in Egypt.