The Sorrows of Empire (25 page)

Read The Sorrows of Empire Online

Authors: Chalmers Johnson

Tags: #General, #Civil-Military Relations, #History, #United States, #Civil-Military Relations - United States, #United States - Military Policy, #United States - Politics and Government - 2001, #Military-Industrial Complex, #United States - Foreign Relations - 2001, #Official Secrets - United States, #21st Century, #Official Secrets, #Imperialism, #Military-Industrial Complex - United States, #Military, #Militarism, #International, #Intervention (International Law), #Law, #Militarism - United States

A large number of military contractors work in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia on various chores, including helping the army operate and maintain its equipment and training and equipping local militaries. After the Camp Doha killing, a spokesman for the army, Major Steve Stover, merely commented that “the world is a dangerous place, especially for Americans abroad.”

26

THE EMPIRE OF BASES

The presence of American forces overseas is one of the most profound symbols of the U.S. commitments to allies and friends. Through our willingness to use force in our own defense and in defense of others, the United States demonstrates its resolve to maintain a balance of power that favors freedom. To contend with uncertainty and to meet the many security challenges we face, the United States will require bases and stations within and beyond Western Europe and Northeast Asia, as well as temporary access arrangements for the long-distance deployment of U.S. forces.

“T

HE

N

ATIONAL

S

ECURITY

S

TRATEGY OF THE

U

NITED

S

TATES

,”

September 17,2002

During the Cold War, standard military doctrine held that overseas bases had four missions. They were to project conventional military power into areas of concern to the United States; prepare, if necessary, for a nuclear war; serve as “tripwires” guaranteeing an American response to an attack (particularly in divided “hot spots” like Germany and South Korea); and function as symbols of American power.

1

Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has been engaged in a continuous search for new justifications for its ever-expanding base structure—from “humanitarian intervention” to “disarming Iraq.”

I believe that today five post-Cold War missions have replaced the four older ones: maintaining absolute military preponderance over the rest of the world, a task that includes imperial policing to ensure that no part of the empire slips the leash; eavesdropping on the communications of citizens, allies, and enemies alike, often apparently just to demonstrate that no realm of privacy is impervious to the technological capabilities of our government; attempting to control as many sources of petroleum as

possible, both to service America’s insatiable demand for fossil fuels and to use that control as a bargaining chip with even more oil-dependent regions; providing work and income for the military-industrial complex (as, for example, in the exorbitant profits Halliburton has extracted for building and operating Camps Bondsteel and Monteith); and ensuring that members of the military and their families live comfortably and are well entertained while serving abroad.

No one of these goals or even all of them together, however, can entirely explain our expanding empire of bases. There is something else at work, which I believe is the post-Cold War discovery of our immense power, rationalized by the self-glorifying conclusion that because we have it we deserve to have it. The only truly common elements in the totality of America’s foreign bases are imperialism and militarism—an impulse on the part of our elites to dominate other peoples largely because we have the power to do so, followed by the strategic reasoning that, in order to defend these newly acquired outposts and control the regions they are in, we must expand the areas under our control with still more bases. To maintain its empire, the Pentagon must constantly invent new reasons for keeping in our hands as many bases as possible long after the wars and crises that led to their creation have evaporated. As the Senate Foreign Relations Committee observed as long ago as 1970, “Once an American overseas base is established it takes on a life of its own. Original missions may become outdated but new missions are developed, not only with the intention of keeping the facility going, but often to actually enlarge it. Within the government departments most directly concerned—State and Defense—we found little initiative to reduce or eliminate any of these overseas facilities.”

2

The Pentagon tries to prevent local populations from reclaiming or otherwise exerting their rights over these long-established bases (as in the cases of the Puerto Rican movement to get the navy off Vieques Island, which it used largely for target practice, and of the Okinawan movement to get the marines and air force to go home—or at least go elsewhere). It also works hard to think of ways to reestablish the right to bases from which the United States has withdrawn or been expelled (in places like the Philippines, Taiwan, Greece, and Spain).

Given that many of our bases around the world are secret, that some

are camouflaged by flags of convenience, and that many consist of multiple distinct installations, how can anyone assess accurately the scope and value of our military empire? It is not easy. If the Secretary of Defense were to ask his closest aides with the highest security clearances how many bases abroad he had under his control, they would have to reply, using an old naval officers’ cop-out, “I don’t know, sir, but I’ll find out.”

To begin to answer this question two official sources of data must be explored; both are of major importance although they differ in their standards of compilation. The Department of Defense’s

Base Structure Report

(BSR) details the physical property owned by the Pentagon, while the report on

Worldwide Manpower Distribution by Geographical Area

(Manpower Report) gives the numbers of military personnel at each base, broken down by army, navy, marines, and air force, plus civilians working for the Defense Department, locally hired civilians, and dependents of military personnel.

3

Both reports are supposed to be issued quarterly but actually appear intermittently. Neither report is inclusive, since many bases are cloaked in secrecy. For example, Charles Glass, the chief Middle East correspondent for ABC News from 1983 to 1993 and an authority on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, writes, “Israel has provided the U.S. with sites in the Negev [desert] for military bases, now under construction, which will be far less vulnerable to Muslim fundamentalists than those in Saudi Arabia.”

4

These are officially nonexistent sites. There have been press reports of aircraft from the carrier battle group USS

Eisenhower

operating from Nevatim Airfield in Israel, and a specialist on the military, William M. Arkin, adds, “The United States has ‘prepositioned’ vehicles, military equipment, even a 500-bed hospital, for U.S. Marines, Special Forces, and Air Force fighter and bomber aircraft at at least six sites in Israel, all part of what is antiseptically described as ‘U.S.-Israel strategic cooperation.’”

5

These bases in Israel are known simply as Sites 51, 53, and 54. Their specific locations are classified and highly sensitive. There is no mention of American bases in Israel in any of the Department of Defense’s official compilations.

The Manpower Report is the more complete of the two in its worldwide coverage, but the BSR is critically important for two reasons. First,

for every listed site it gives an estimated “plant replacement value” (PRV) in millions of dollars. Second, it gives details on some 725 foreign bases in thirty-eight countries, of which it defines 17 as “large installations” (having a PRV greater than $1.5 billion), 18 as “medium installations” (having a PRV between $800 million and $1.5 billion), and 690 as “small installations” (having a PRV of less than $800 million). According to the Department of Defense, “The PRV represents the reported cost of replacing the facility and its supporting infrastructure using today’s costs (labor and material) and standards (methods and codes).”

Although one must doubt the accuracy of any such estimates, particularly given the Pentagon’s record of incompetent accounting, they are nonetheless useful for making comparisons. Thus, according to Pentagon specialists, Ramstein Air Force Base near Kaiserslautern, Germany, the largest NATO air base in Europe, has a PRV of $2,458.8 million; whereas Kadena Air Force Base in Okinawa, the largest U.S. facility in East Asia, has a PRV nearly twice as large, at $4,758.5 million (and its adjoining Kadena Ammunition Storage Annex adds another $964.3 million). These are astronomical sums even though they probably underestimate real replacement values. In its detailed reports by country, the BSR lists foreign bases only if they are larger than ten acres and have a PRV greater than $10 million. Sites that do not meet these criteria are aggregated for each country as “other.” Only places with null or zero PRVs are not counted at all. These include small sites such as single, unmanned navigational aids or air force strategic missile emplacements. The 725 foreign bases, including the installations listed as “other,” have a total replacement value, according to the Pentagon, of $118 billion. This is a mind-boggling aggregation of foreign real estate and buildings possessed by the United States.

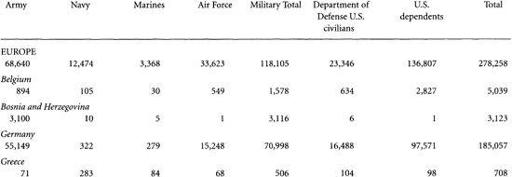

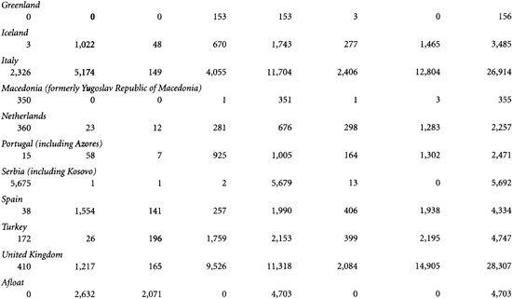

By contrast, the DoD’s Manpower Report does not list individual bases, only countries. It found that in September 2001, the United States was deploying a total of 254,788 military personnel in 153 countries. When civilians and dependents are included, the number doubles to 531,227. Since the Manpower Report does not say what the assignments are within a particular foreign country, one cannot distinguish between a country with American bases and a country with merely some embassy

guards, a few special forces on a training mission, and perhaps some communications clerks. Therefore, it seems useful to consider only those countries with at least a hundred active-duty military personnel. These are likely to be assigned to bases. The total then, according to the DoD’s Manpower Report, is thirty-three, which comes close to the BSR’s list of significant bases in thirty-eight countries.

There are some major discrepancies between the BSR and the Manpower Report that are not easily explained. To give one important example, the BSR for September 2001 does not have any entries for Bosnia-Herzegovina or for Yugoslavia, Serbia, or Kosovo. The Manpower Report for the same month gives 3,100 for the number of army troops in Bosnia and 5, 675 for the number of army troops in the Serbian province of Kosovo. It is possible that Camp Eagle in Bosnia (built in 1995-96) and Camps Bondsteel and Monteith in Kosovo (both of which went up in 1999) were omitted intentionally in order to disguise their purpose—of protecting oil pipelines rather than contributing to international peacekeeping operations.

With such caveats, the table on pages 156-160 offers a snapshot of the American empire in terms of military personnel deployed overseas just before September 11, 2001. In the months following, the United States radically expanded its deployments everywhere but particularly in Afghanistan, elsewhere in Central Asia, and in the Persian Gulf.

Numerous bases are “secret” or else disguised in ways designed to keep them off the official books, but we know with certainty that they exist, where many of them are, and more or less what they do. They are either DoD-operated listening posts of the National Security Agency (NSA) and the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), both among the most secretive of our intelligence organizations, or covert outposts of the military-petroleum complex. Officials never discuss either of these subjects with any degree of candor, but that does not alter the point that spying and oil are obsessive interests of theirs.

The United States operates so many overseas espionage bases that Michael Moran of NBC News once suggested, “Today, one could throw a dart at a map of the world and it would likely land within a few hundred miles of a quietly established U.S. intelligence-gathering operation....

FOREIGN DEPLOYMENTS OF U.S. MILITARY PERSONNEL AT THE TIME OF THE

TERRORIST ATTACKS ON THE WORLD TRADE CENTER AND THE PENTAGON

By Region and Country

September 2001

Only those countries with at least 100 active-duty U. S. military personnel are listed. Totals of the listed countries do not add up to the regional totals because the latter include all countries with any U.S. troops, regardless of the size of the contingent.