The Sorrows of Empire (27 page)

Read The Sorrows of Empire Online

Authors: Chalmers Johnson

Tags: #General, #Civil-Military Relations, #History, #United States, #Civil-Military Relations - United States, #United States - Military Policy, #United States - Politics and Government - 2001, #Military-Industrial Complex, #United States - Foreign Relations - 2001, #Official Secrets - United States, #21st Century, #Official Secrets, #Imperialism, #Military-Industrial Complex - United States, #Military, #Militarism, #International, #Intervention (International Law), #Law, #Militarism - United States

Since at least 1981, what had once been an informal covert intelligence-sharing arrangement among the English-speaking countries has been formalized under the code name “Echelon.” Up until then the consortium exchanged only “finished” intelligence reports. With the advent of Echelon, they started to share raw intercepts. Echelon is, in fact, a specific program for satellites and computers designed to intercept nonmilitary communications of governments, private organizations, businesses, and individuals on behalf of what is known as the “UKUSA signals intelligence alliance.” Each member of the alliance operates its own satellites and creates its own “dictionary” supercomputers that list key words, names, telephone numbers, and anything else that can be made machine-readable. They then search the massive downloads of information the satellites bring in every day. Each country exchanges its daily intake and its analyses with

the others. One member may request the addition to another’s dictionary of a word or name it wants to target. Echelon monitors or operates approximately 120 satellites worldwide.

The system, which targets international

civil

communications channels, is so secret that the NSA has refused even to admit it exists or to discuss it with delegations from the European Parliament who have come to Washington to protest such surveillance. France, Germany, and other European nations accuse the United States and Britain, the two nations that originally set up Echelon, with commercial espionage—what they call “state-sponsored information piracy.”

17

There is some evidence that the United States has used information illegally collected from Echelon to advise its negotiators in trade talks with the Japanese and to help Boeing sell airplanes to Saudi Arabia in competition with Europe’s Airbus. In January 1995, the CIA used Echelon to track British moves to win a contract to build a 700-megawatt power station near Bombay, India. As a result, the contract was awarded to Enron, General Electric, and Bechtel. During October 1999, European activists and government officials held a “Jam Echelon Day,” spending twenty-four hours sending as many messages by e-mail as possible with words like

terrorism

and

bomb

in them to try to overload the system.

Echelon’s existence has given great impetus to more or less unbreakable systems of encryption, such as what are called random one-time pads. These use keys known only to sender and receiver and are secure against all forms of cryptanalysis. The plaintext message is encrypted using computer-generated random numbers and never used again. The sender and the receiver must use the same key, the weak point being getting the key to the recipient via some tamperproof channel, commonly a CD sent through the mail.

18

One-time pads are a development to which the NSA is extremely hostile. However, knowing that the NSA has access to all forms of electronic communications, users seeking privacy have naturally turned to coded messages. The NSA, in turn, is reported to be trying to get Microsoft to include secret decoding keys known only to it in all its software.

The problem with Echelon is not just that nations occasionally use it to promote their commercial activities, or simply that it is a club of

English speakers, or even that it can be defeated by fiber-optic cables and encryption. The fatal flaw of Echelon is that it is operated by the intelligence and military establishments of the main English-speaking countries in total secrecy and hence beyond any kind of accountability to representatives of the people it claims to be protecting. Among the resultant travesties was the case of a woman whose name and telephone number went into the Echelon directories as those of a possible terrorist because she told a friend on the phone that her son had “bombed” in a school play.

19

According to several knowledgeable sources, the British government has included the word

amnesty

in all the system’s dictionaries in order to collect information against the human rights organization Amnesty International. Even though the governments of the world now know about Echelon, they can do nothing about it except take defensive measures on their messaging systems, and this is but another sign of the implacable advance of militarism in countries that claim to be democracies.

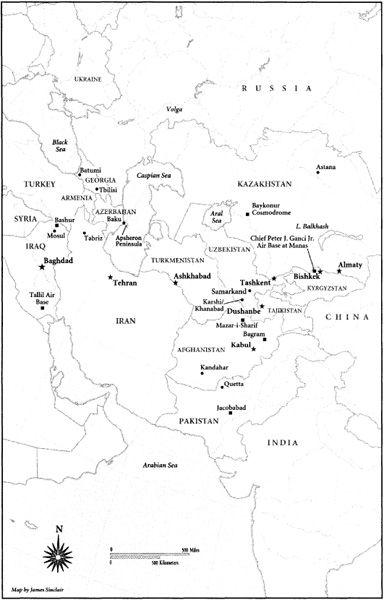

As I have said, no single purpose can possibly explain the more than 725 American military bases spread around the world. But the government’s addiction to surveillance certainly explains where some of them are and why they are so secret. Another explanation for some of the bases is the staggering level of American dependence on foreign sources of oil, which grows greater by the year. Many garrisons are in foreign countries to defend oil leases from competitors or to provide police protection to oil pipelines, although they invariably claim to be doing something completely unrelated—fighting the “war on terrorism” or the “war on drugs,” or training foreign soldiers, or engaging in some form of “humanitarian” intervention. The search for scarce resources is, of course, a traditional focus of foreign policy. Nonetheless, the United States has made itself particularly dependent on foreign oil because it refuses to conserve or in other ways put limits on fossil fuel consumption and because multinational petroleum companies and the politicians they support profit enormously from Americans’ profligate use. A year after the 9/11 attacks, General Motors’s sales of its 5,000-pound gas-guzzling Chevrolet Suburban SUV, which gets thirteen miles to the gallon, had doubled.

20

Starting with the CIA’s 1953 covert overthrow of the government of Iran for the sake of the British Petroleum Company, American policy in

the Middle East—except for its support of Israel—has been dictated by oil. It has been a constant motive behind the vast expansion of bases in the Persian Gulf. America’s wars in the oil lands of the Persian Gulf are the subject of a later chapter; what I want to explore here are some other cases in which oil is the

only

plausible explanation for acquiring more bases. In these cases, the government has produced elaborate cover stories for what amounts to the use of public resources and the armed forces to advance private capitalist interests. The invasion of Afghanistan and the rapid expansion of bases into Central and Southwestern Asia are among the best examples, although there are several instances from Latin America as well.

Oil is a very old subject around the Caspian Sea and especially in the city of Baku, capital of Azerbaijan, itself located on the Apsheron Peninsula that juts into the Caspian from its western shore. In the thirteenth century, Marco Polo commented on springs in the region giving forth a black fluid that burned easily and was useful for cleaning the mange of camels. Baku was also the site of the “eternal pillars of fire”—obviously oil-fed—worshiped by the Zoroastrians. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was the place where the Nobel brothers, Robert and Ludwig, revolutionized oil-drilling techniques and methods of transporting oil to world markets, thereby laying the foundations for their own vast fortune and that of the Rothschild family of Paris. In the patent of a third Nobel brother, Alfred, the inventor of dynamite and later the creator of the Nobel Prize, lay the roots of the successes of the DuPont company in the United States and of Royal Dutch Shell in the Netherlands. Baku’s oil was Hitler’s target in the Caucasus until his armies were stopped and defeated at Stalingrad.

In 1978, while traveling in Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia, I took a swim in the Caspian and could not help noticing its slightly oily texture and smell. At that time, however, the region was better known for Beluga sturgeon and caviar, since during the years when only two nations, the USSR and Iran, bordered on the Caspian Sea, the oil and gas of the basin remained largely underdeveloped. The Soviets preferred to invest in their vast Siberian oil fields and left the Muslim areas of the Caspian to produce primarily for local markets. Iran, of course, has its own oil fields.

After the breakup of the USSR in 1991, five independent nations suddenly bordered the sea—Russia, Iran, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan—and the modern race to control the oil and gas resources of the region began. It was led by American-based multinational oil companies, soon to be followed by the U.S. military in one of its more traditional and well-established roles: protector of private capitalist interests. As retired Marine Lieutenant General Smedley Butler, winner of two congressional Medals of Honor, wrote way back in 1933, “I spent thirty-three years and four months in active military service.... And during that period I spent most of my time as a high-class muscle-man for big business, for Wall Street, and the bankers.... Thus, I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street.... In China I helped to see to it that Standard Oil went its way unmolested.”

21

During the 1990s and especially after Bush’s declaration of a “war on terrorism,” the oil companies again needed some muscle and the Pentagon was happy to oblige.

Nobody knows exactly how much oil and gas there is in the Caspian Basin, since it has been poorly surveyed. The Energy Information Administration of the U.S. Department of Energy conservatively estimates that proven reserves in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan are just under 8 billion barrels but that possible reserves may well reach over 200 billion barrels. Natural gas reserves are, for Turkmenistan, 101 trillion cubic feet proven and 159 trillion cubic feet probable and, for Kazakhstan, 65 tcf proven and 88 tcf probable. Turkmenistan may have the eighth-largest gas reserves in the world. (The agency defines proven reserves as oil and natural gas deposits that are 90 percent probable and possible reserves as deposits that are 50 percent probable.)

22

The Bush administration’s national energy policy document of May 17, 2001, known as the Cheney Report, notorious because one of its chief sources of information was the chairman of the now discredited and bankrupt Enron Corporation, suggests that “proven oil reserves in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan are about twenty billion barrels, a little more than the North Sea.”

23

These

proven reserves, whose value hovers between $3 trillion and $5 trillion, might supply all of Europe’s petroleum needs for eleven years.

24

Two other elements add to the prospects of great profits: labor costs are extremely low and environmental standards nonexistent.

Even if the Caspian Basin is not the El Dorado that some claim, it is the world’s last large, virtually undeveloped oil and gas field that could for a time compete with the Persian Gulf in supplying petroleum to Europe, East Asia, and North America. It seems to have about 6 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves and 40 percent of its gas reserves.

25

China, which has the world’s fastest-growing economy, became a net oil importer in November 1993 and continues to try to negotiate a possible pipeline from Kazakhstan to Shanghai via Xinjiang Province. China is also attempting to obtain oil from Russia via a pipeline that would stretch from Angarsk in Siberia to the Daqing oil field in Manchuria.

26

Imagining the five Central Asian republics that became independent when the USSR broke up in 1991 as potential suppliers of oil to the United States, however, involves numerous problems. Kazakhstan (by far the largest in terms of land area), Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan all share frontiers with China. Turkmenistan borders on Iran. Uzbekistan, in the center, is the only one that abuts all the others plus Afghanistan. All except one are ruled by former Communist Party apparatchiks. Only President Askar Akayev of Kyrgyzstan was not a former Soviet boss, and he has arranged for all fuel for the military jets flying out of the U.S. base in Kyrgyzstan, the biggest American garrison in Central Asia, to be supplied by a firm owned by his son-in-law.

27

All the leaders of these Central Asian republics have hopeless human rights records, the two worst being the president of Uzbekistan, where the big U.S. air base at Khanabad is located, and the president for life in Turkmenistan, who has established a personality cult surpassing that of Stalin and who has placed all oil revenues in an offshore account that only he controls. Even Kazakhstan, which is relatively developed and sophisticated—the famous Russian Cosmodrome that launched the world’s first space missions is located at Baykonur in south-central Kazakhstan and the country has a population that is 35-40 percent Russian—is hardly a model republic. Its foreign minister revealed that in 1996 President

Nursultan Nazarbayev moved $1 billion in oil revenues to a secret Swiss bank account without informing his parliament.

28